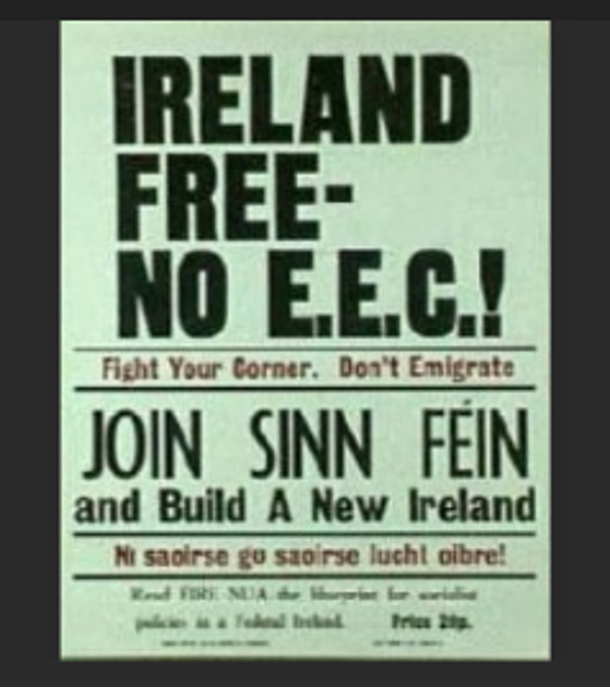

As the Irish establishment gears itself up to stage an enormous hooteanny to celebrate next year’s 50th anniversary of the state’s being accepted as a member of the then European Economic Community (EEC) on January 1, 1973, the fishing sector will attend in the manner of Banquo’s Ghost.

It has always been thus, and few people argue with any sort of conviction that the deal which the Irish negotiators made regarding access to fishing rights within our territorial waters was pretty much a disaster. Estimates of the value lost in raw catch run into the tens of billions.

It is slightly ironic then that the country at the centre of the latest blow to the sector is Norway, where in 1972 the electorate defied their own political elite and rejected membership, to a large extent based on the belief that membership would be bad for its thriving fishing sector. Another referendum was held in 1994 and with a similar outcome.

Norway exports over €10 billion in value of fish produce every year, with an estimated 35 million people eating fish from Norway every day. Key to that is the high value processing sector which employs thousands of people and contributes significantly to Norwegian GDP. There are over 6,000 fishing boats plying the seas in contrast to Ireland’s paltry 180 of which over a third are currently negotiating decommissioning.

While we can only admire the Norwegian people for being smarter than the people they elect, and tip our hats to their optimum use of their own natural resources including oil and gas, Irish fishermen pay part of the cost. For, somewhere in the region of 90% of the landed catch in Norway comes from the fisheries under the nominal control of other countries, or subject to international agreements.

One of those international powers is, of course, the EU which basically controls Irish fisheries and dispenses quota to all of the other member states without much of our bye or leave. Likewise, it has an arrangement whereby Norway engages in reciprocal agreements to allow their boats fish in EU waters and EU boats in the artic cod zone.

However, as the Chief Executive of the Irish Fish Producers Organisation (IFPO), Aodh O’Donnell, pointed out last week after meeting the Fisheries Commissioner, Irish fishermen get no part of that reciprocal deal.

The current problem facing Irish fishermen is that the EU is in the process of allowing the Norwegians to increase its share of quota in EU waters by 81% and the Norwegians are determined to utilise that to mostly take blue whiting from within Irish waters. In overall terms, while Irish boats have 3% of the quota for EU waters, Norway a non-member, has 18%.

That partly reflects the relative strengths of the two fishing sectors, but Ireland’s weakness is itself a consequence of 50 years of one of our key resources having been handed over to others by the EU with the collaboration of successive Irish governments. This has led to a situation where 64 of the Irish fishing fleet of 180 are currently in negotiations to decommission.

That paid scheme to exit the sector is part of the Trade and Co-Operation Agreement that finalised the exit of Britain from the EU. To facilitate that the Irish government agreed to offer up more of our fishing rights to ensure that they earned another pat on the head from their new besties in Brussels. Recall how the green jersey was brandished when all of that was going on.

So ironically, the departure of our old nemesis and the naïve role played by our lads in all of that, has facilitated not an extension of our hold on waters which were common fishing grounds for the English and Scottish boats as well as our own but a further sea grab by our dear friends in “Europe.”

They, like a New York crime family on the departure of one of the old outfits has divvied up part of their racket to satisfy the New Jersey bosses. If the EU was cast as Goodfellas, Ireland would be Spider. Still hobbling about until they decide to finish him off.

On the day that history recalls the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Free State, it is perhaps worth recalling what one of those who signed the Treaty had to say about our fisheries. In one of his last speeches, made in August 1922, Michael Collins – in setting out a vision of a country that would avoid both “old commercial capitalistic lines,” and “State Socialism” – referred directly to the fishing sector. He pointed out that it was “neither the source of renumeration it should be to those engaged in it, nor the source of profit it could be to the country.”

At a time when his successors appear determined to complete the transformation of this part of Ireland into a resource for international capital with its dependency on free movement of capital and labour and the destruction of all national and cultural barriers that remain in its path, perhaps some of them might do worse than read what Collins and others of the Revolutionary Dáil Eireann actually said rather than turn him into an icon for their blandness.

They might also reflect on the fact that Ireland is approaching the day when we might have no domestic fishing fleet. An island where fishing forms no part of the economy, other than for tourists maybe. A land of beaten down gillies, strangers in their own land. Just as the English always wanted us to be, but can now be achieved as good Europeans.