In a move that possibly reflects public unease, the Department of Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth (DCEDIY) has amended its protocol on Ukrainian refugees travelling back and forth between that country and Ireland.

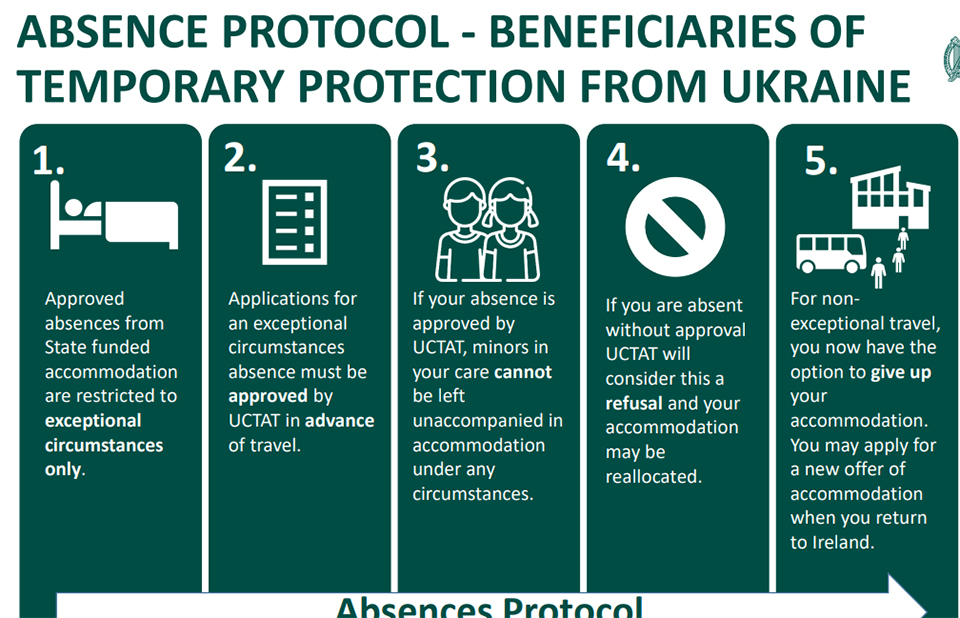

The new protocol was to take effect from last Monday and means that people can only be absent from state provided accommodation in “exceptional circumstances.” Prior to that Beneficiaries of Temporary Protection (BOTP) could be absent for seven days over a six month period. However, there is anecdotal evidence of Ukrainian refugees who are regularly flying back and forth.

As with other “misinformation,” the relevant authorities eventually accepted that it was a serious enough matter to require official intervention. As Gript has highlighted, there are other questions that need to be asked about both the nature and the composition of Ukrainian migration to Ireland.

Nobody can be considered to be a genuine refugee if they can go on holidays, or regularly visit, a country from which they are supposedly fleeing in fear of their lives. Given that this state has one of the highest per capita rates of Ukrainian refugees in the whole of Europe and that the guts of €2.5 billion were set aside in last week’s Budget to pay for this, there is a clear need to tackle abuse.

In explaining the decision, the Department referred to the pressures on accommodation, and to the “constrained supply” of accommodation to people coming to Ireland. They might perhaps refer to the EU Directive which as Gript has previously pointed out allows states to impose limits due to capacity constraints.

The Directive which the state and NGOs and others refer to when claiming that we cannot impose any limits is Council Directive 2001/55/EC. Article 25.1 of the Directive sets out clearly that member states do have a right to determine the numbers of refugees which they will accept in line with their “capacity to receive such persons”. (My italics added below)

Article 25

- The Member States shall receive persons who are eligible for temporary protection in a spirit of Community solidarity. They shall indicate – in figures or in general terms – their capacity to receive such persons. This information shall be set out in the Council Decision referred to in Article 5. After that Decision has been adopted, the Member States may indicate additional reception capacity by notifying the Council and the Commission. This information shall be passed on swiftly to UNHCR.

It is pretty obvious when one looks at the large gap between the per capita intake here as compared to France, for example, that the French and other states have in one way or another indicated that they have capacity issues. The Department with primary responsibility in this matter now recognises this. The solution would appear to be in plain view.

The Directive also makes it clear that no state is obligated to take anyone indiscriminately who claims to be seeking temporary protection. “(22) It is necessary to determine criteria for the exclusion of certain persons from temporary protection in the event of a mass influx of displaced persons.”

That would surely apply to persons who are abusing the system as persons who are regularly travelling back and forth surely are. States may also exclude or deport persons who have previous convictions for serious criminal offences. (Article 28.1 (ii)

Finally, it needs to be stressed too that the Directive refers to “temporary” protection. Article 4 specifically refers to TP being granted for a period of one year, with automatic extensions for up to a one year period, assuming that the crisis which led to the influx is still in place.

It does not mean, nor ought it to mean, that tens of thousands of Ukrainians be encouraged to stay here for ever. That is the clear implication of much of the official narrative here, with even civil servants – as Gript has previously noted – brainstorming mad notions such as building new towns for Ukrainian refugees, as an email within the Department suggested in March last year..