Yesterday, the Director of Public Prosecutions lodged an appeal against the sentence given to Cathal Crotty for his assault on Natasha O’Brien in Limerick in 2022 – on the basis that, in handing down a suspended sentence, the judge showed “undue leniency”.

Reports of the sentencing led to an outpouring of outrage and widespread media commentary, while Ms O’Brien said that she felt the judiciary needed to “do better”, and that she would like to see judges receive “sensitivity training” to help them deal with victims of crime.

The DPP’s office says that appeal court judges will consider a sentence ‘unduly lenient’ only if they believe the trial judge made a mistake on a legal point. “The appeals court will not change a sentence just because they think the sentence was too light or because they would have given a different sentence,” it explains.

The events of the past week, and previous controversies over suspended sentences, indicate that this is an issue of concern for the Irish public.

A survey by the Department of Justice in 2021 asked respondents which specific aspects of the Irish criminal justice system they felt were in the greatest need of improvement. “Responses to this question were spontaneous and no prompting was provided by interviewers,” the Department’s report said.

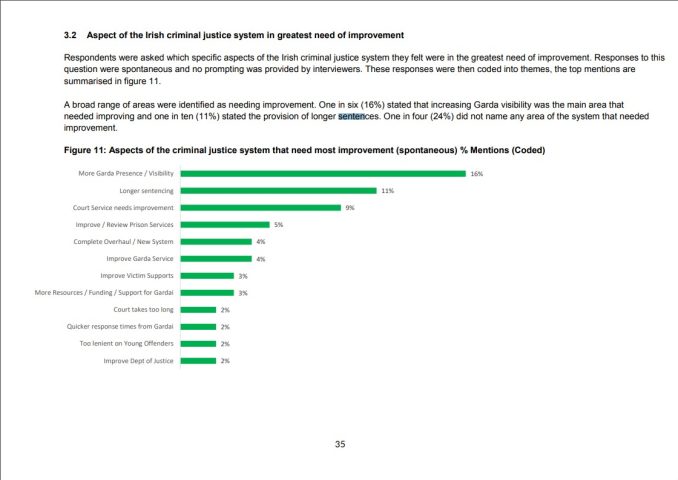

While the leading issue raised by respondents (one in six or 16 per cent) was increasing Garda visibility, the next most commonly mentioned issue raised by 11 per cent of people taking the survey was the provision of longer sentences.

As can be seen in the graph above another 2 per cent felt the criminal justice system was “too lenient on young offenders”, while the same number felt the court process “takes too long”.

Protests were held across the country after the news of the suspended sentence handed down to Crotty broke, and demands were made for the courts to hand down tougher sentences particularly when it came to violence against women and sexual assault.

Welcoming the DPP’s decision to appeal the Crotty’s sentence, Natasha O’Brien said: “I know the DPP is impartial to public opinion and government opinion, however I have no doubt there would not have been an appeal had their not been a national uproar.”

She is very likely correct, although the DPP’s office could never acknowledge this was the case, but their decision, and the furore around the case, should draw attention to the work of an influential NGO which seeks to reduce rather than increase prison sentences, and, in fact, has as its mission a “just, humane Ireland where prison is used as a last resort”.

This is important because the work of the Irish Penal Reform Trust is, as always, backed by taxpayers funds – with the Department of Justice, the Department of Rural and Community Development and the IHREC committing almost €1.5 million since 2019 to the Trust’s work.

That work, according to their website, has an important goal: “a national penal policy which is just, humane, evidence-led, and uses prison as a last resort”.

The Trust says it advocates for a “progressive criminal justice system that prioritises alternatives to prison, upholds human rights, and champions reintegration”.

They seem very much opposed to sending criminals to prison, offering alternatives such as “community-based sanctions and alternatives to custody for low-level

offences”, which they say should help “to ensure that imprisonment becomes a sanction of last resort in reality”.

Its worth, I think, asking victims of crime whether they believe that prison should become a “last resort”, especially in light of the public anger being expressed about sentencing in the past week or more.

The Trust claims that it “clearly influenced the 2020 Programme for Government” and lists the many occasions it made submissions to and appeared before various Oireachtas Committees seeking to sway elected representatives regarding its mission.

It hopes to “influence relevant national policy and legislation so that effective non-custodial responses are the default response to less serious offending,” adding that it will measure success when “the principle of imprisonment as a last resort is embedded in policy, expressed in legislation, and reflected in practice.”

The Trust previously recommended “Judicial training on sentencing and awareness-raising among professional groups, lawyers and judges about the availability and features of community sanctions.”

It also argues that “imprisonment itself causes serious social harms, and therefore should only be used sparingly at the point of sentencing when non-custodial alternatives are not available or are deemed inappropriate” – and opposes mandatory sentencing and “presumptive minimum’ sentencing – where a judge must apply a specific minimum penalty, except under exceptional circumstances.

It is difficult to say how much influence organisations like the IRPT actually has on sentencing and on the mindset in the legal system, and there are important issues under debate regarding the influence and purpose of sentencing and penal policies.

It goes without saying that the IPRT is perfectly within its rights to call for prison reform, and it does important work around prisoners rights and assisting children of incarcerated prisoners. But its stance is clearly at odds with the calls for tougher sentencing we’ve heard on a daily basis since the ruling in the Natasha O’Brien case.

Again, they are absolutely permitted to have a mission that looks for more, instead of less, severity in sentencing – because the real issue here is that, as ever, the political establishment is speaking out of both sides of its mouth.

Much of the political outrage we saw last week, from the impassioned speeches to the standing ovation in the Dáil, was from the same people who also oversee funding and supporting an entire NGO who thinks prisons are a bad thing and should only be used as a “last resort”.

(The IPRT lists as one of its achievements the cancellation of plans to build a super-prison in Thornton Hall. They seem to have less to say about current plans to build an enormous asylum centre there instead, though they have issued a report expressing concern about Irish judges leaning heavily “on the presumption that foreign nationals with no links to the State present a greater flight risk than Irish nationals”.)

In fact, Labour Leader, Ivana Bacik, is a patron of the Irish Penal Reform Trust. Last week she called on the Minister for Justice “to confirm that she will initiate a review of sentencing practices, in particular the practice of suspending custodial sentences in cases of violent crime. It is time to act decisively to ensure that our legal system delivers true justice and support for victims of violent crimes.”

How does patronage of an organisation which seeks to minimise prison sentencing marry with a call to urge the Minister for Justice to “act decisively” to deliver justice in the context of a case where a suspended sentence provoked public outrage.

There is certainly a public perception that a too-lenient attitude is becoming more prevalent in the courts regarding criminal behaviour, and critics point to cases such as the recent suspended sentence handed down to an English language student who climbed into the bedroom of his 79-year-old landlady and proceeded to sexually assault her.

The problem – as ever in Ireland, to the point where it seems deliberate and for the purpose of obfuscation – is the lack of data on sentencing. Current data about sentencing is “profoundly limited and inadequate for its tasks”, a report from the Judicial Council Sentencing Guidelines and Information Committee (SGIC) found in 2023.

The lack of a central dataset which offers insights into real-world sentencing practices, is a “dire” risk to public confidence, the report says.

We ought to have no confidence either in a political establishment which on the one hand funds and supports an NGO seeking to have prisons used only as a “last resort”, while also making empty gestures around sentencing when the public mood darkens because a sentence is suspended.

Interestingly, Limerick solicitor, Sarah Ryan, said this week that the criticism of Judge Tom O’Donnell’s ruling in the Crotty case showed a “disregard for fairness, balance, and dignity by some elements of the media”.

She said that: “Respect and dignity remained the hallmarks of Judge O’Donnell’s court, whether it be the district or circuit court. I was not ever in doubt that his decisions were made following much thought, conscientiously, and only after careful consideration of the information before the court.”

We don’t know, in fact, if sentencing overall has become more lenient – or if judges are influenced by campaigns or shifting culture which argue that rehabilitation and the rights of criminals might be more important than the punishment of wrongdoing and imprisonment as a reflection of society’s rejection of a certain type of behaviour.

Perhaps the government and opposition might enable a rigorous and transparent method of gathering such data – and also adopt a consistent position in terms of sentencing and funding NGOS seeking to impact same.