One of the terms that is certain to have you pegged as a conspiracy theorist if you ever happen to throw it in as an icebreaker at an evening soirée is ‘Replacement Migration.’. Tickets for the Aviva or Bohs might disappear, sharpish.

It is particularly associated with Renaud Camus who published a book Le Grand Remplacement, The Great Replacement, in 2011. As with many so-called trigger words it is the term itself, rather than the substance of the argument, which attracts outrage and avoids discussion of the substance.

Even where a person does not use the term, nor agree with Camus’ theory behind it, reference to evidence of radical demographic changes in Europe will generally be seized upon as proof that even someone who refers solely to official population statistics belongs over into the corner with tin foiled coiffured Q Anon types.

It may come as a surprise then that the concept of population replacement did not originate with Camus and that in March 2000, the Population Division of the United Nations Secretariat published a report entitled Replacement Migration: Is it a Solution to Declining and Aging Populations?

The object of the exercise was to examine various scenarios and to estimate “what levels of international migration that would be needed to offset declines in the size of population, the declines in the population of working age, as well as to offset the overall ageing of a population.” The focus of the study was Europe, Japan, Russia, the United States and South Korea.

The central scenario posed was what level of migration would be needed to ensure that the working age populations in 2050 would remain the same as in 2000. That was regarded as the minimum to ensure the maintenance of productivity and public provision.

In the situation where almost all of the countries concerned were expected to experience continued falls in fertility the level of projected migration was accepted to be “extraordinarily high.” They are no longer regarded as such.

Interestingly, given the accepted narrative here that large scale immigration is required to offset aging and “pay the pensions” of elderly natives, the report refers to studies which found that “immigration is not a realistic solution to demographic ageing” for the simple and logical reason that evidence suggested that “immigrants adopt the low fertility of a host population.” (p10.)

The fact that an increasing proportion of the housing demand is being supplied by one and two bed units means that immigrants will indeed face the same pressures as Irish households when it comes to being able to have children – which supports the declining migrant fertility thesis.

We recently looked at statistics which show that while almost 30% of births are to mothers of other than Irish nationality that this would appear to be a function of overall population demographics driven by labour migration of younger people, and not higher birth rates.

The Irish state is only referred to in the context of what in 2000 was the 15 member European Union. The only estimate for the population here is that in a medium scenario of moderate migration patterns that the population would have increased by 1.1 million between 1995 and 2050 to 4.7 million.

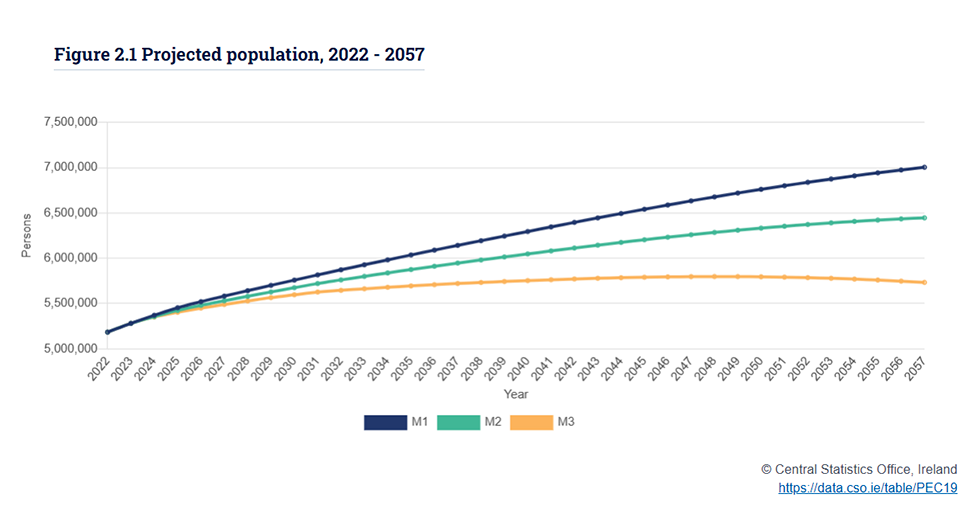

As we have seen, the CSO is now estimating that, in either a medium or high migration scenario, the population will be between 6.3 million and 6.7 million by 2050 and that the population will be up to 7 million by 2057.

What is almost never discussed is that at that stage 40% of the population of the state will have been born overseas.

The 2000 United Nations projections for population growth and migration if the working age population was to be maintained show that it was reasonably accurate. Germany as the largest EU state is of particular interest.

In 1995, the population of Germany was 81.7 million. The UN estimate was that this would increase to 92 million by 2050 and reach 87.5 million by 2025. The estimated population of Germany now is 84 million and during the period between 1990 and 2025 the proportion of the overseas born population grew from 6.4% to just over 20%.

The United Kingdom stands out as one of the case studies in which the projected population increase was far greater than predicted. The UN estimate was for the UK to have a population of 62.2 million by 2025 if the working age population was to be maintained largely through immigration. The current population estimate is 68.5 million.

In 1990, the overseas born population of the UK made up 6.5% of the total figure. It was 17% in the 2022 Census and is likely over 20% now. It is evident that as in Ireland and Germany and other European countries that UK population growth is overwhelmingly driven by immigration.

Japan is also one of the case studies in the report and the UN projection estimated that the population of Japan would need to reach 141 million by 2025 if the working age population was to be maintained. It actually stands at 125 million. A gross under-estimate in comparison to the European countries.

The UN has estimated that Japan would require 46 million migrants up to 2050, but at present the overseas born population only stands at 3%. The Japanese have – despite a fertility rate that has long been below replacement – made a conscious decision not to follow what the UN and others would seem to accept as inevitable.

Japan is no longer the third major economy on the planet and demographics have been cited as one of the reasons for a long-term decline in growth rates. It still remains a prosperous country and despite its size and density is considered to be one of the safest countries in the world.

One of the key reasons for that given all the other likely correlations is that demographic homogeneity leads to social stability. Have the Japanese made that choice at the expense of economic metrics?

That raises the question as to whether other countries and particularly northern hemisphere democracies with a strong Christian tradition need to consider those factors ahead of the Golden Calf of constant growth as measured by GDP.

That is a heretical proposition but it may need to be posed: How best do nation states balance the demands of Capital – which is increasingly global and antipathetic to local concerns other than their impact on their operations – against those of a stable, healthy society.

Population replacement is clearly taking place regardless whether that is in the context of the prosaic and strikingly accurate estimates of the United Nations – or as a topic for debate about whether it is a good thing or not.