The Book of Invasions, the medieval mythological origin story of the Irish, tells of the arrival of Míl Espáine in Ireland over 3000 years ago. Sergio Fernandez Redondo, reviews the Gaelic manuscript Lebor Gabála Érenn and compares it to the corroborating accounts in Spanish historical manuscripts.

Īth mac Bregoin athchonnairc hĒrinn ar tūs, fescor gaimrid, a mulluch Tūir Bregoin; dāig is amlaid is ferr radharc duine, glan-fescor gaimrith»

It was Íth, Breogán’s son, who first saw Ireland from the top of Breogán’s tower on a winter afternoon; as this is the best way to see it, on a clear winter afternoon.

Thus states the Lebor Gabála Érenn or Book of the Invasions of Ireland, the Irish mythical story which narrates the arrival of the Gaelic people on the island from the north of Spain.

Despite its name, what we know as Lebor Gabála Érenn is a collection of tales present in multiple Irish mediæval manuscripts, The Book of Leinster (12th century) being the best preserved of these.

According to the narrative in the Book of Invasions, which probably stems from older legends from the Celtic oral tradition which were first recorded in writing by early Christian monks, Ireland received six progressive invasions until the Gaels settled definitively on the island.

After the Genesis and diaspora of nations, the people of Cessair, grandson of Noah, are the first to set foot on the island, until all bar one are annihilated by a flood. They are followed by the people of Partholón, three hundred years later —also from Noah’s lineage through Magog—, after an odyssey through Gothia, Anatolia, Greece, Sicily and Iberia. All except one of these people perish due to a plague and, after thirty years, there arrive the people of Nemed, also descendants of Magog. As an aside, we ought to mention the Fomorians: a supernatural race that already inhabited the island prior to the arrival of Partholón and that symbolise nature’s chaotic and destructive forces —therefore comparable to the Nordic jötnar or the Greek Titans— and who were confronted on the battlefield by both Partholón’s and Nemed’s people. It is in fact after one of these fierce battles that the surviving Nemedians abandon the island, splitting into three groups. The first group settle in Britain and become the ancestors of the Britons, the second group venture north, and the third one head for Greece.

This last group is enslaved in Greece and, after two hundred and thirty years, they return to Ireland, bearing now the demonym Fir Bolg. Their five chieftains divide the island into the traditional five provinces, whereof four have survived. And it is now that the second group of descendants of Nemed return to Ireland, after having learnt magic and druidic arts in the north, in the guise of the supernatural Tuatha Dé Danann or people of the goddess Danu (of clear Hyperborean inspiration). After the Battle of Magh Tuireadh, the Tuatha Dé Danann expel the Fir Bolg to the remote western islands and become rulers of Ireland, and will remain so for the next one hundred and fifty years, with occasional skirmishes against the Fomorians.

“The Fomors”, illustration by John Duncan (Credit: Dundee Art Museum, Dundee)

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

The last and definitive invasion takes place afterwards: the Gaels. The Book of the Invasions relates how these people also descend from Magog and from a Scythian prince who partook in the construction of the Tower of Babel. The son of this prince, Goídel Glas marries Scota, daughter of an Egyptian pharaoh, and he synthesises the Gaelic tongue from the linguistic confusion following the collapse of the Tower of Babel. Thereafter, they embark on an exodus from Egypt which will take them to Scythia, Crete, Sicily and, finally, Iberia. It is here where Íth, Breogán’s son, descries Ireland on the horizon and launches his first expedition, wherein he encounters the three kings of the Tuatha Dé Danann. Nevertheless, he is murdered in strange circumstances and his men return the corpse to Iberia, provoking the indignation of the Gaels and the preparation of a punitive expedition under the command of the brothers of Íth and the sons of Míl Espáine. This last personage, Gaelicisation of the Latin Miles Hispaniæ (soldier of Hispania), and which certain manuscripts present as the husband of (another) Scota, appears to have fundamental relevance since he bestowed upon the Gaels the eponymic demonym Milesians.

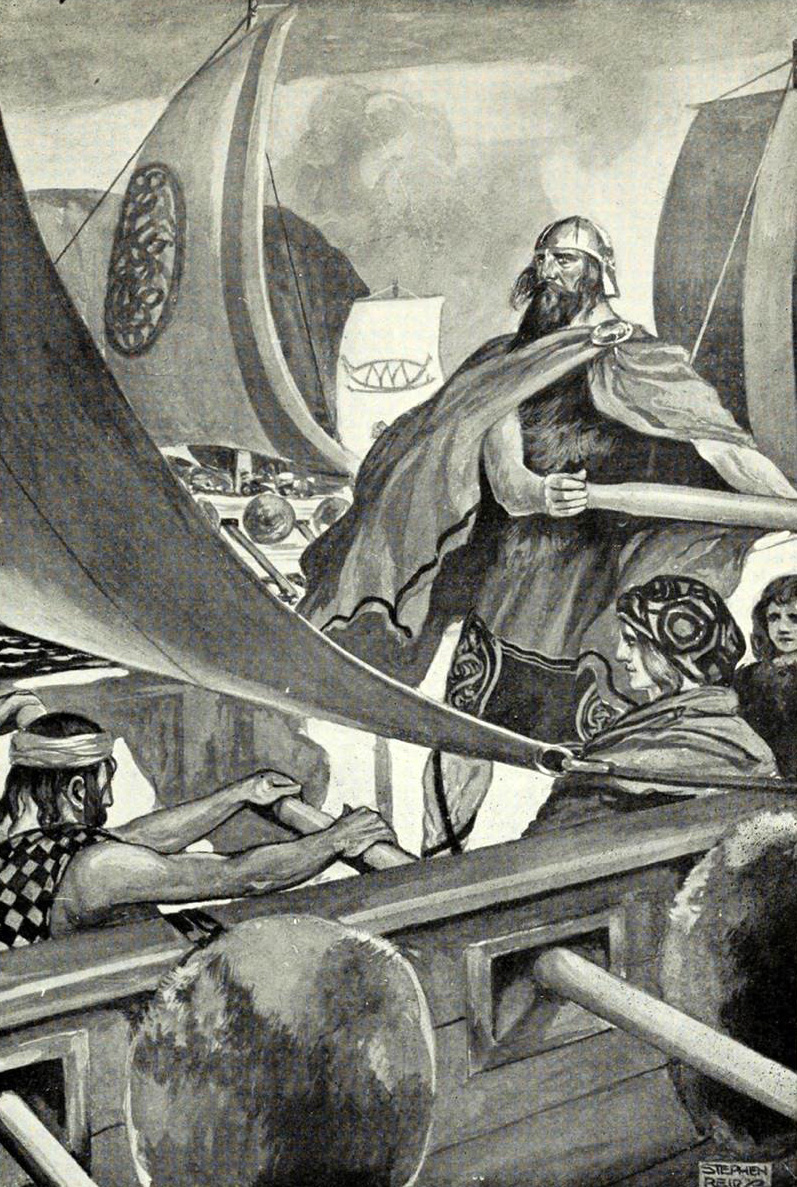

This last expedition finally pits the Milesians against the Tuatha Dé Dannan, leaving behind several foundational myths along the way, such as the island’s current name, having been assigned by the Milesian bard Amergin after a promise to a local princess named Ériu. The aforementioned bard plays a fundamental role, as he recites some verses which break the spell wherewith the druids of the Tuatha Dé Danann tried to prevent the Milesians’ landing. Legend attributes to said verses the honour of being the first literary work in the Irish tongue. Once victory of the Milesians is consummated, they proclaim themselves kings of the island, whereas the Tuatha Dé Danann are exiled into the underworld, becoming the Aes Sídhe of the faerie legends and giving birth to the rich Irish mythological culture that survived until the present day. The narration concludes with a chronicle of subsequent kings, first pagan and then Christian, whereupon it starts to blend into historical chronicles documented contemporarily.

“The Coming of the Sons of Miled”, illustration by Stephen Reid (public domain)

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

Biblical references are evident: deluges, exodi and tales from the Old Testament interweave together harmoniously with pre-Christian legends and local idiosyncratic interpretations. This type of semi-Biblical foundational narrative is not infrequent amongst European peoples who escaped direct Romanisation and which, thereby, try to justify their civilised essence —Nordic Israelism being another fine example—. The purported Levantine origin of the Irish, their assimilation to the sons of Israel and their Egyptian, Scythian or Greek journeys are therefore to be expected in this type of narrative, but their Iberian stage raises new questions. Subsequent instances of Spain in mediæval tales add yet more interest to this conundrum, such as The Tragedy of the Sons of Tuireann, wherein the protagonists reside in the court of a Spanish king in order to steal his magic chariot (although some antiquarians interpret that place as Sicily); or The Courtship of Momera, which narrates the sojourn of the king of Munster Éogan Mór in Spain and his marriage to a Castilian princess with whom he would then return to Ireland; or the very story of princess Tailtiu, daughter of the king of Spain Móg Mór and adoptive mother of Lug —pan-Celtic god of notable presence on the Iberian peninsula as attested by ethnonymy, toponymy and Celtiberian epigraphy—. In this respect, we can find multiple equivalences between the mythologies, customs and toponymies of both countries.

The character of Breogán, together with the reference to a tower, lead traditionally to the quasi-unanimous assimilation of this place with Brigantia, current La Coruña (although Betanzos and Bragança have also been proposed), whose Tower of Hercules seems to have been erected by the Romans over an older construction. Evidently, this legend had significant importance in Galicia, which adopted it as a foundational myth, although it did not enjoy the same popularity in the rest of the peninsula. In contrast, the Book of the Invasions had an enormous relevance throughout Irish history. The Irish always held in high regard the myth that justified their civilised essence despite absence of Romanisation, especially during the English domination and its vindication based on the supposed civilising labour of the British contingent. Not surprisingly, the Spanish section of the narrative reached its zenith of popularity during the apogee of the Spanish Empire. This purported bond with the greatest world power and, to boot, allied in the struggle against the English invader, was welcome with much enthusiasm by Irish people.

Statue and Tower of Breogán in La Coruña (Credit: Luis Miguel Bugallo Sánchez)

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

We have multiple accounts on how important the Spanish bond was at the time. Fynes Morison, the English secretary of Lord Mountjoy, wrote extensively on his experience in Ireland in the early 17th century in his magnum opus Itinerary. Among many other subjects, he touches upon the linguistic mores of the locals, much to his chagrin:

…the meere Irish disdayned to learne or speake the English tounge, yea the English Irish and the very Cittizens (excepting those of Dublin where the lord Deputy resides) though they could speake English as well as wee, yet commonly speake Irish among themselues, and were hardly induced by our familiar conversation to speake English with vs, yea common experience shewed, and my selfe and others often obserued, the Cittizens of Watterford and Corcke hauing wyues that could speake English as well as wee, bitterly to chide them when they speake English with vs. Insomuch as after the Rebellion ended, when the itinerant iudges went theire Circutes through the kingdome each alfe yeare to keepe assises, fewe of the people no not the very iurymen could speake English, and at like sessions in Vlster, all the gentlemen and common people (excepting only the iudges trayne) and the very iurimen putt vpon life and death and all tryalls in lawe, commonly spake Irish, many Spanish, and fewe or none could or would speake English.

Putting aside his vexation at the obstinacy in speaking Irish of both the “mere Irish” and the Anglo-Irish, it is most remarkable that one would sooner hear Spanish than English in certain parts. These linguistic customs seem to be backed up by the report of a Spanish spy in Ireland during the Nine Years’ War in the 1590s. In a letter sent back to Spain with strategic information for a future Spanish intervention, he recommended Baltimore as landing port on account of Spanish being spoken by a large percentage of the local population. The historian Florián de Ocampo reiterates again the myth in his Crónica General de España (1553), where he speaks of a Spanish king Brigo (Breogán?) who placed dwellers on the island of Ireland. Most interestingly, Florián also relates the following anecdote from his personal experience in Ireland:

Acuerdome yo que siendo llegado con fortuna de la mar en una villa de la tal isla nombrada Catafurda, los moradores della con otros que de fuera venian, mostrauan mucho placer con los españoles que por allí nos juntamos, y nos tomaban por las manos en señal de buen conocimiento, diziendonos deçender ellos de linage español…

(I recall how, having arrived by fortune of the sea in a village of that island named Catafurda*, the dwellers thereof, with others who came from outside, showed great pleasure with the Spaniards there gathered, and they took our hands in sign of good knowing, telling us that they descended from Spanish lineage…)

* It is thought that Catafurda is a phonetic approximation of Waterford

The abovementioned Nine Years’ War, last attempt of the Irish nobles to finally eradicate British rule on the island, saw Spanish participation on the side of the Gaelic faction (Hugh O’Neill even went as far as offering the Irish crown to Philip II of Spain). Donal Cam O’Sullivan Beare, Prince of Beare and one of the last Gaelic chieftains to capitulate, wrote a letter to Philip II offering submission to his authority in a last desperate attempt to save the Gaelic cause. Said missive, written in Irish, began as follows: «We, the true Irish, long since deriving our root and original from the most famous and most noble race of Spaniards, and from Milesius, […] as the testimonies of our most venerable antiquities, our histories, and our chronicles declare […]». The war ended in a resounding victory for the English, who established definitively their dominion over the island and forced the rebel chieftains, and many of their allies, to abandon Ireland forever in what has come down in History as The Flight of the Earls.

By virtue of the Treaty of Dingle, through which Charles V had already conferred some decades before citizenship rights and other privileges to Irish emigrants in Habsburg Lands, many of the exiles settled in Spain, custom perpetuated over the following centuries. The Count of Caracena, at the time governor of Galicia —region where most ships from Ireland would arrive—, wrote to the King Philip III a letter extolling the character of the Irish, referring to them as «nuestros hermanos españoles del norte» (our Spanish brethren from the north). The Irish were always warmly welcome in Spain and enjoyed more privileges than other immigrants because they were not seen as foreigners, but as fellow Spaniards. These Irishmen, many of noble birth, enjoyed great prestige in Spain and occupied high-ranking positions, producing an array of important historical characters —including prominent soldiers, politicians and even a prime minister or Latin-American liberator, as it happens—.

Leopoldo O’Donnell y Jorris (1809-1867), Spanish general and prime minister on several occasions (Credit: Army Musæum, Toledo)

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

The exile prompted the foundation of numerous Irish colleges across the Spanish geography, under patronage of the Spanish Crown. These institutions would provide education for Irish catholic priests over the following centuries, making them invaluable for the preservation of Irish culture during the challenging years of the Penal Laws. It is symbolically significant that the first of these colleges, the Irish College at Salamanca, was founded in 1592, the same year as Trinity College in Dublin. Whilst the impending Anglicisation and Protestantisation of Ireland was initiated on the island, Gaelic culture found a haven across the Celtic Sea in Spain. Michael Doheny, in his memoir of Geoffrey Keating, makes the following revealing claim:

Spain was, in fact, the principal refuge for the exiled Irish, and his opportunities for preserving his practical knowledge of his native tongue, were far greater there than elsewhere out of Ireland.

It was also around that time that the aforementioned Geoffrey Keating wrote his renowned Foras Feasa ar Éirinn, a history of Ireland of higher literary than academic value. In addition to the stories of the Book of the Invasions, the Bordeaux-educated priest provides some other interesting pieces vis-à-vis the subject of this article. He recalls the theory of the classical name Hibernia —influenced, but not determined, by the Latin hībernus (winter)—, which in turn comes from the Greek Ἰουερνία (Iouerníā), deriving ultimately from the Spanish river Ibērus —current Ebro, and also origin of the term Iberia—. He also mentions a tale relating how three Spanish fishermen, by the names of Capa, Laighne, and Luasad, count among the first inhabitants of the island.

As a last example of the general prevailing sentiment in those times, the exiled archbishop of Tuam, Florence Conry, wrote to the King Philip III in these terms:

And the Ancient Irish, as these are descended from the Spanish, desire always to be governed by the Kings of Spain and their successors, and bear affection and love to the Spanish nation. Likewise great hate and enmity to their enemies and are sharp of wit and valiant in war, altogether like the Spaniard.

Moving forward in time, the Enlightenment witnessed another increment in the popularity of these legends. This period fostered an incipient patriotic movement which began to question the morality of the Penal Laws —in turn justified by English and Scottish like David Hume with the, by now, hackneyed tarradiddle of British civilisatory tutelage—. Irish antiquarians of the calibre of Charles O’Conor or Sylvester O’Halloran started to investigate the island’s remotest past to demonstrate the existence of a rich literary culture in pre-Norman Ireland, and the Book of the Invasions returned to the fore again as proof of the Irish civilised nature.

Irish College at Salamanca (Credit: José Luis Filpo Cabana)

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

Still in more recent times, there are some who see a gesture to the Milesians in that stance from Amhrán na bhFiann that mentions some of the Irish coming from beyond the wave (Buíon dár slua thar toinn do ráinig chugainn), although most probably it refers to the Hiberno-Americans who supported the independence movement.

Recent research from scholars like John Koch and Barry Cunliffe —who challenge the Hallstatt-La Tène theory in their book Celts from the West and posit the origin of Celtic culture on the Iberian Peninsula through linguistic, archæological and genetic analyses— seems to confer certain veracity to this myth. Their conclusions would explain the arrival of the Celts in Ireland from the Iberian Peninsula through a process linked to the expansion of the Atlantic megalithic phenomenon, although these theories have not yet received unanimous academic approval.

In any case, let us not forget that we are dealing with one of the many foundational myths that bestrew European folklore and, as such, it is merely a legend. Nevertheless, are not legends, frequently, but fanciful and exaggerated representations of actual events perpetuated through oral tradition? One thing is certain: those who, like yours truly, hail from the north-west of Spain, will barely stifle a nostalgic sentiment when gazing upon the green meadows of the Emerald Isle.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Barnwell, David and Rodríguez Alonso, Carmen (2009/2022) Diccionario Irlandés-Español Foclóir Gaeilge-Spáinnise. Dundee: Evertype

- Céitinn, Seathrún (1634/2009) Foras Feasa ar Éireann. Ex-classics Project

- Crespo McLennan, Julio and Downey, Declan M. (editors) (2008) Spanish-Irish relations through the ages. Dublin: Four Courts Press

- Céltica (2020) La leyenda de Eoghan Mor, el rey de Munster que se casó con una princesa española. https://www.celtica.es/la-leyenda-de-eoghan-mor-el-rey-de-munster-que-se-caso-con-una-princesa-espanola/

- Koch, John (2010) Celtic from the West: Alternative Perspectives from Archaeology, Genetics, Language and Literature. Oxford: Oxbow Books

- Lady Gregory (1905/2006) Gods and Fighting Men. Dublin: Nonsuch Publishing

- Leersen, Joep Theodor (1986) MERE IRISH & FÍOR-GHAEL. Studies in the idea of Irish nationality, its development and literary expression prior to the nineteenth century. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamin’s Publishing Company

- Lux Occulta (2011) Competing Powers: Conor O’Mahony, Spain and England. https://lxoa.wordpress.com/2011/08/26/competing-powers-conor-omahony-spain-and-england/

- Kew, Graham David (1995) Shakespeare’s Europe Revisited: The unpublished Itinerary of Fynes Moryson (1566-1630). Birmingham: The University of Birmingham

- Ní Lionáin, Cliodhna (2012) El Libro de las Invasiones – La creación, utilización y apropiación de un artefacto cultural. Gallaecia n. 31, pages 169-180

- Ocampo, Florián de (1553) Los cinco libros primeros dela Cronica general de España, que recopila el maëstro Florian do Campo, Cronista del Rey nuestro señor, por mandado de su magestad, en Çamora. Medina del Campo: printed by Guillermo Millis

- O’Curry, Eugene (1855) Cath Muighe Léana, or the battle of Magh Léana; together with Tochmarc Moméra, or the courtship of Momera. Dublin: Celtic Society

- O’Halloran, Clare (2004) Golden Ages and Barbarous Nations. Antiquarian Debate and Cultural Politics in Ireland, c. 1750-1800. Cork: Cork University Press

- O’Halloran, Sylvester (1772/2019) An Introduction to the Study of the History and Antiquities of Ireland, in which the assertions of Mr Hume and Other Writers are Occasionally Considered. Illustrated with copper-plates. Also two appendixes: containing 1. Animadversions on an introduction to the history of G. Britain and Ireland, by J. Macpherson, Esq. 2. Observations on the memoirs of Great-Britain and Ireland, by Sir John Dalrymple. Miami: HardPress

- Stewart Macalister, R.A. (1935/2020) Lebor Gabála Érenn. The book of the taking of Ireland. Dublin: Irish Texts Society

Sergio Fernández Redondo hails from Asturias, in northern Spain, and is located in Co. Waterford. Although he has degrees in engineering and translation, his range of interests encompasses History, linguistics, economy and political philosophy. An enamoured of Irish culture and languages, his inevitable (and enduring) latest endeavour is to master the language that produced the first vernacular literature in Europe.