Although there is no specific reference to Ireland, a report on Tuesday by Bloomberg on plans by Intel to lay off thousands of its 110,000 employees will have perhaps caused some shudders among policy makers in Dublin, especially as it follows some recent poor growth figures.

According to Intel Ireland it has 4,900 people working for them in Ireland so it is a shrewd guess that some of the job losses – which might be announced this week as the company prepares to post second quarter earnings – will be among those employed here. At the end of 2022, around 2,000 Intel workers here were offered three months unpaid leave as part of an earlier cost cutting exercise.

The company site claims that it employs 66 different nationalities in Ireland and the statistics on work permits for persons from outside of the EU/EEA alone show that in the last five years, to the end of June this year, Intel brought 982 people to work here from third countries alone. That excludes people working here who have come from other EU states.

Yet despite the 2022 scare over layoffs Intel was issued that year with 364 work permits for employees from outside of the EU/EEA. Similar work permit statistics are available for other major corporations in the technology sector. That means not only are most of the corporation earnings here exported but, as figures we examined last year showed, most tech jobs are being filled by people coming from overseas, and indeed from outside of the EU/EEA.

Intel is just one example of the potentially precarious dependence of the Irish economy on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) particularly in the technological and pharmaceutical sector. Intel is one of the biggest contributors of the large corporations which paid €23 billion of the overall €88.1 billion in taxes collected here in 2023.

The Intel alarm comes hot on the heels of reports that GDP contracted by 5.5% in 2023, a revised CSO estimate, and that although the second quarter GDP figure this year was up on that for the previous three months, it had fallen by 1.4% compared to the second quarter of 2023.

Ironically, following years and years of worshipping at the feet of the Golden Calf of GDP, some commentators have been moved, as was the RTÉ person on Monday, to note that “GDP is not generally considered a great indicator of the underlying health of the Irish economy, because it includes distorting effects related to the activities of multinational firms.”

Indeed it is not, and I have explained why it is not on previous occasions, so is the establishment finally admitting that the GDP figure is pretty much meaningless with regard to the actual health of the Irish economy? Are they furthermore acknowledging that this is rather a precarious position to be in?

It is not beyond the bounds of possibility that, whatever boon the huge corporation tax haul currently is from allowing them to base their operations here, the whole thing could collapse pretty quickly. That might be the case if the likes of Intel and others contact globally, and if the threats to that taxation structure follow upon signals from both camps in the US Presidential elections.

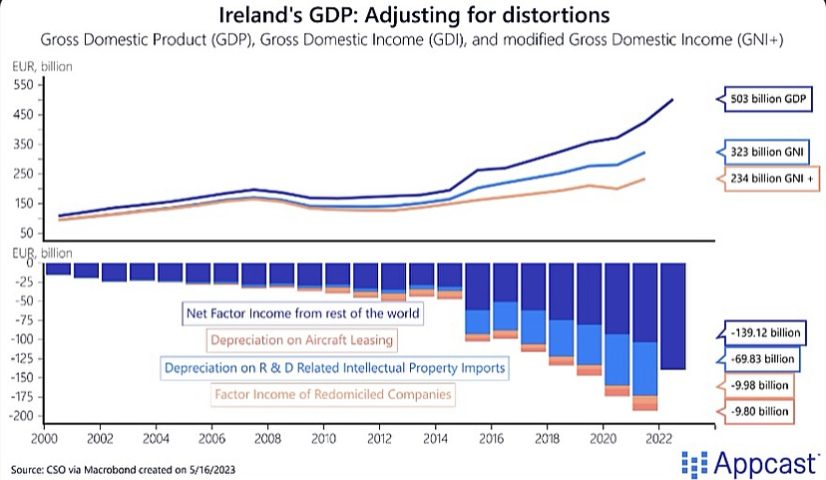

The table above from a 2023 paper by Julius Probst shows exactly how the export of corporate earnings distorts the Irish economy. I previously showed that of the overall GDP for the Irish state in 2021 of $504 billion that $121.6 billion was exported in the form of corporate earnings.

That is what the above table shows as Net Factor Income, which when subtracted from GDP provides the Gross National Product (GNP) or Gross National Income (GNI). So in effect, 24% of the wealth created here was exported in 2021. The table above appears to show that this increased to 27.6% in 2023.

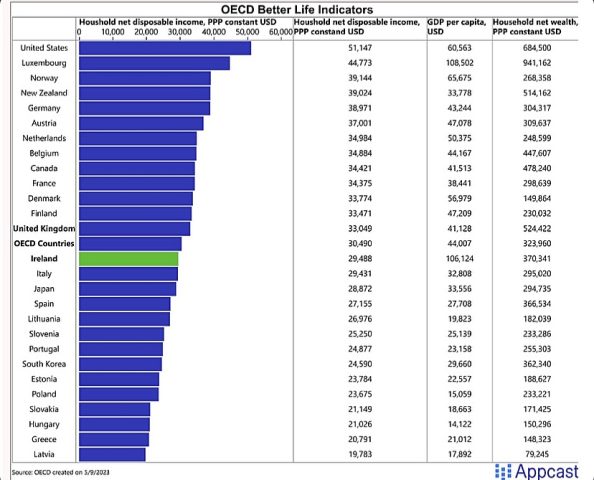

Probst also provides the table below which shows that while Ireland had the second highest per capita GDP according to September 2023 OECD statistics, we were below the OECD average for net disposable household income. That means GDP is almost totally unrelated to the relative individual prosperity of Irish citizens.

All of this raises questions about the nature of the Irish economy and society that requires far deeper analysis. As with the intimately connected issue of mass immigration – which is mainly driven by economic factors both through work permits and what is effectively economic migration disguised as asylum – it is a question of what sort of country we want to live in.

To put it bluntly, even if we avoid any backdraft from corporate downsizing, are we content to not only host the likes of Intel for tax reasons, but to facilitate them basing their operations here on a workforce that is mostly comprised of migrants?

Are we then in an unending absurd scenario where whatever taxes Intel and other corporations pay are then increasingly devoted to public provisions for those migrants? Similar to the genius who suggested that we need to import more builders in order to build more houses for more overseas builders, computer nerds, lifelong dole merchants and all.

All to get a cut of profits that are in any event mostly exported rather than reinvested here. Allied to that is a huge rentier economy as epitomised by the growing hold of overseas funds in the housing and rental market. Not to mention the considerable, and indeed unquantifiable, stake that external interests have in the multi billion asylum accommodation sector.

The problem which the founders of the Irish state had in attempting to encourage domestic capitalist economic development was that a huge proportion of the wealth generated was not only held by people and institutions that at very best were indifferent to the fortunes of the independent 26 counties but which was largely invested overseas, at that time through the London stock exchange and financial system.

The problem now appears not dissimilar when it comes to dependency. If we are happy to continue in that dependent relationship then well and good. If not, and if people who are unhappy with the consequences of all that wish to change course then thinking caps need to be placed on the relevant heads. Before it is too late.