A guest speaker and workshop lead in DCU’s course for SPHE teachers – which led to controversy because of exercises featuring ‘fisting’ and writing a detailed sex scene – argues that young children ‘do sexuality’, and repeatedly challenges “heteronormative” assumptions of “children’s presumed sexual innocence”.

Prof EJ Renold has written that her work seeks “to challenge the often heteronormative, highly gendered and ageist assumptions of young children’s presumed sexual innocence” in the media and in current “sex education policy and guidance.”

She has posited that there exists a “pervasive ideology of childhood innocence in the United Kingdom and throughout the Western world,” and that this ideology is “coupled” with a “conspiracy of silence surrounding children’s own sexual cultures.”

According to the professor “discourses of innocence profoundly endanger children” and that “such is the denial of children being sexually aware that any early interest in sex is interpreted as a warning sign that the child has been sexually abused.” Sexual innocence is, the professor quotes “something that adults wish upon children, not a natural feature of childhood itself.”

“Young children,” the professor states, “know and explore sexuality with each other, but – aware of adults’ need for childhood innocence – often keep this secret.”

She has written that presumptions of innocence in children were used to legitimate “whiteness”, “the family” and “hetronormativity” – and that thinking of childhood as being antithetical to sexuality was a “white, middle-class” concept.

The professor has stated that her research and writing has been designed to “encourage what could be described as a ‘queering’ of childhood” – and recently argued that children aged 0-5 years express sexuality through sexual behaviours.

The Welsh professor – who DCU lecturer Dr Leanne Coll was “delighted” to welcome to the course for SPHE teachers as a “guest speaker and workshop lead” – takes issue with “panics” in which she says childhood is “represented as a time of presumed innocence and under attack”.

She has argued that parents must not have the right to remove their children from RSE/SPHE lessons – a recommendation accepted by the Welsh government.

‘CHILDREN, SEXUALITY & SEXUALISATION’

In an introduction to the book, Children, Sexuality and Sexualisation, Renold and her co-editors – R. Danielle Egan and Jessica Ringrose – say its chapters offer “an alternative way of thinking about the child as an inherently sexual being as opposed to sexuality being a pathological outcome.”

They claim “the book’s arguments offer more reasoned approaches, thereby de-escalating the anxiety that can enter into conversations about the sexuality of children,”

They argue that a “problematic effect” of “sensationalist” texts expressing concern around child sexualisation is to deny “girls’ sexual agency, rights, pleasure and desires”. To this effect, they point to a paper written by Renold with one of her co-editors, Jessica Ringrose – which says that “public and private anxieties over the sexualization of girls” are not a new phenomenon – and “have a long and contested history”.

The book includes a quote from one researcher who says: “Children’s sexuality, in so many contexts, turns out to be ‘more complicated than we supposed’. ‘We might’ – if we let ourselves explore these complications – ‘find (new) stories that are not fueled by fear’.”

Renold, who is a professor at Cardiff University, and her co-editors also argued that “child sexualisation discourses” have the “problematic effect” of “overemphasizing the victimization and objectification of girls, thereby reducing any sexual expression as evidence of ‘sexualization’.

The book claims that data from “very young children” (aged from 3 upwards) shows that children are “always already sexualized” because they are gendered (seen as boys and girls), and through emphasis on future ambitions around marriage and special relationships and having babies.

The editors – in asking “what next in the field of children’s sexuality studies” – warn of the need to be prepared for “braving the backlash when we endeavour to introduce notions of sexual pleasure, sexual rights or sexual citizenship”.

The editors say that “the child’s sexuality” was always imbued with assumptions of innocence in order to “legitimate” the “colonial project, whiteness, the family and heteronormativity”.

“However, the modern history of ideas on childhood sexuality is distinct in that it is more often than not plagued by fear, projection, fascination and consternation. As historians and childhood studies scholars have illustrated, the history of the sexual child differs from other populations deemed sexually deviant or in need of sexual protection because of Anglophone conceptions of childhood,” they add.

“Most dominant discourses that have emerged within the Anglophone West have, on the surface, conceptualized childhood as antithetical to sexuality (however, this tends to primarily apply to white upper-middle-class children).”

One chapter of the book involves a “queer reading” of a Japanese cartoon genre which Renold and co-authors acknowledges “often features erotic and relational exchanges between boys, as well as boys (boy-loving or BL) and non-human animals and other non-human figures” .

The author of the chapter, Anna Madill, “shows how a paedophilic interpretation (its dominant reading under English law) ignores the transgressive ways in which these texts can be read and raises some key challenges and questions for the Anglophone West of ‘how intelligible, meaningful, non-paedophilic frames are available for reading non-realistic, erotic texts involving visually young characters’.

Renold and her co-editors conclude that they hope the book “might inspire the next generation of childhood sexuality scholars to continue to ask questions that challenge and subvert what we think we know about children, childhood and sexuality, and collaborate on research projects which foreground children’s own sexual experiences in all their diversity and complexity”.

“JUNIOR SEXUALITIES”

Renold is also the author of Girls, Boys and Junior Sexualities which is committed to “exploding the myth of the primary school as a cultural greenhouse for the nurturing and protection of children’s (sexual) innocence,” saying “children locate their local primary school as a key social and cultural arena for doing ‘sexuality’”.

Age and maturity – in relation to primary school children – are considered social constructs in Renold’s writings.

Each key finding [of her book] is selected specifically to challenge the often heteronormative, highly gendered and ageist assumptions of young children’s presumed sexual innocence in the wider media and current UK sex education policy and guidance”, she says.

Renold writes, also adding that “one of the projects of this book is to encourage what could be described as a ‘queering’ of childhood.

In a paper written for the NSPCC and Cardiff University Renold argues that “‘sexualisation’ is frequently described as something that happens to children, rendering them passive victims and denying their role as active and critical meaning makers”.

Other lecturers in the team who delivered the SPHE course for school teachers in DCU have worked with Renold in relation to preparing a new RSE curriculum in Welsh schools, including Dr Leanne Coll, who wrote to the SPHE teachers taking part saying they had “the absolute pleasure of welcoming Prof EJ Renold and Dr Ester McGeeney to the DCU campus as guest speakers and workshop leads”.

Renold was a key member of a Welsh panel who insisted that sex education begin in primary schools at age 3, and argued strongly that parents should not be allowed to take children out of RSE classes – because, they said, a child had a right to sex education.

“The panel recommends that RSE should be statutory in the curriculum for all schools from Foundation Phase through to compulsory school leaving age (3-16),” they wrote – also arguing that “the potential for building sexualities and relationships education curricula for preschool aged children is enormous and necessary”.

Renold worked with another contributor to the DCU course who lectured Irish SPHE teachers during the diploma, Ester McGeeney, on a report recommending a revamp of sex education in Welsh schools.

SAYS CHILDREN AGED 0 – 5 EXPRESS SEXUALITY

In that report, ‘Informing the Future of the Sex and Relationships Education Curriculum in Wales’ they argue that there should be a statutory requirement that children in Wales, aged 3-16, should be taught SRE.

They argue that children’s “learning and experience” of sexuality “begins as soon as they enter the social world” – and claim that research suggests those designing sex education “curricula for the early years” may “need to question our assumptions about what is commonly understood as “developmentally appropriate””.

“Frequently children and young people are viewed as ‘innocent’ or ‘pre-sexual’ beings, sparking unproven concerns within schools about the potential for SRE to ‘corrupt childhood innocence’ or ‘prematurely sexualise’ young people,” the report on sex education in Wales, produced by Renold and McGeeney said.

“Yet expressing sexuality through sexual behaviours and relationships with others is a natural, healthy part of growing up. For example, for children aged between 0-5, behaviours such as holding or playing with own genitals, curiosity about other children’s genitals, interest in body parts and what they do and curiosity about sex and gender differences reflect ‘safe and healthy development’ (see Brook 2015)”.

McGeeney co-led a workshop on the DCU course which advised SPHE teachers in post-primary schools on how they would answer questions such as ‘What is your best advice on giving head’ and ‘Do chest binders hurt?’ and ‘Do you think there are more than two genders?’ The slide suggested: “Keep it factual and just be as open and honest as you can. It’s not your job to give advice about how to have good sex or to discuss personal preferences!”

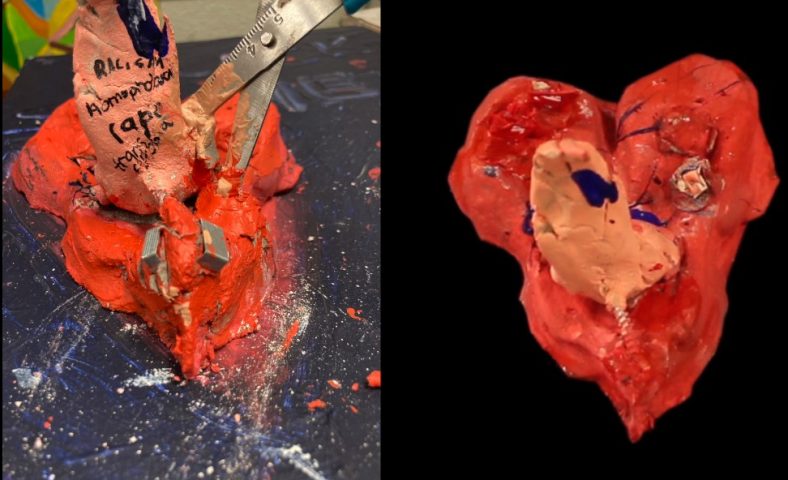

In the section of the DCU course led by Renold, a video was shown of artwork undertaken by school students as part of RSE exercises, some of which teachers on the course described as “disturbing”.

Renold refers often in her writings to Queer Theory, which argues that the widely-understood understanding of ‘male’, ‘female’, ‘gay’, ‘straight’, and more are actually social constructs rather than reflecting reality.

“Queer theory enables a thinking Otherwise about the heteronormativity of these gender identities and the sexualisation of gender and the gendering of sexualisation in children’s identities more widely,” she writes in Girls, Boys and Junior Sexualities.

Along with academic Judith Butler, Queer Theory is strongly influenced by the ideas and worldview of Michel Foucault, a French philosopher who signed an open letter arguing that French law was contradictory because it recognised that 12- and 13-year-olds had a capacity for legal discernment, but rejected “such a capacity when the child’s emotional and sexual life is concerned”.

In their introduction to Children, Sexuality and Sexualisation, Renold and her co-authors say that “In his first volume on the history of sexuality in Western Europe, Foucault notes that the child’s sex was the object of intense scrutiny and pivotal in the deployment of a shifting disciplinary apparatus which foregrounded the project of normalization and surveillance in the late 19th century (Foucault, 1980). As with most ideas on sexuality, cultural values ebb and flow at various periods, and ideas about the sexual child are no different.”

DCU and Prof Renold have been contacted for comment.