According to the annual estimates published by the Central Statistics Office (CSO) and covering the period between Census 2016 and Census 2022 a total of 364,100 persons of non-Irish nationality came to live in the state.

During the same period a total of 178,100 non-Irish people left the state to return home to their own country or to another. That means that there was a net inward migration, according to the CSO of 186,000.

The number of Irish people who left the state between 2016 and 2022 was 166,800, another factor in the changing demographics. The long-term trend over the past 20 years has been net emigration by Irish people, although the much greater numbers who returned during the exceptional Covid lockdown years of 2020 and 2021 shows a small inward net migration of Irish people between 2016 and 2022.

Even with the lockdown the numbers of non-Irish people who came here between April 2020 and April 2021 was greater than the number of Irish people who returned.

The migration trends ought to be reflected in other official statistics including the number of persons recorded in the Census as having been born outside of Ireland, and the number of Personal Public Service (PPS) numbers that were issued.

A detailed look at the Census tables from 2011, 2016 and 2022 shows that the number of persons who said that they had been born outside of Ireland was 766,700 in 2022; 810,406 in 2016 and 1,015,355 in the last Census taken in May 2022.

In proportional terms the percentage of the population of the state born outside of Ireland has risen from 16.7% in 2011, to 17% in 2016 to 20% in 2022. The overall increase between Census 2016 and Census 2022 was 204,949. Which corresponds fairly closely to the net inward migration of non-nationals we identified as 186,000.

So, in fairness to the CSO it is perhaps the presentation of the statistics rather than the CSO’s own accounting which causes confusion and misconceptions. Some of that is certainly deliberate on the part of some of those cherry picking from the findings, rather than any intent by the CSO itself.

It might also be noted that the numbers of persons who responded adequately to that part of the Census was 62,971 fewer than the official population in 2011, 71,944 in 2016, and 64,342 fewer than Census 2022. Almost 5% of households in 2022 did not return a form, a potential gap of over 200,000.

Readers may recall that when Census 2022 was published that I was one of the very few to point out the large and increasing numbers born overseas. The headline figure that was picked by mainstream media and others for their own purposes was the % of persons living in the state who held citizenship in other countries. This is a red herring given the large numbers of immigrants who have been awarded Irish citizenship.

(That confusion also requires a caveat to be entered with regard to the study by Alan McSweeney which compared Census 2016 to PPS issues between 2001 and 2016 as McSweeney was also referring to citizenship rather than birthplace. However, his overall point regarding the underestimation of immigration and its influence on overall population estimates remains.)

The main gap between the Census figures and the subsequent CSO population estimates is that between the officially estimated level of immigration and the numbers of people born overseas and the amount of PPS numbers that are issued to persons of other than Irish nationality.

My previous analysis of all the relevant statistics on work permits, student visas, asylum application and other officially recognised channels for being granted permission to remain for whatever length of time in the state showed that the CSO estimate of 112,000 non Irish immigrants between April 2022 and April 2023 was less than half of the number of PPS issues to persons from overseas.

It was also significantly less than half of the figure calculated from permits, student visas, asylum statistics etc. Most indicative of all perhaps is that the number of PPS issues to non-Irish nationals of 236,819 correlates very closely to the 230,447 that I calculated from the official statistics on work permits, asylum applications, education visas and others.

Between 2017 and 2022 there were a total of 1,185,035 new PPS numbers issued. Of that total, 771,813 were issued to persons of other than Irish nationality. Irish-born persons and the children of immigrants born in Ireland accounted for just 413,222 of that figure which was just under 35%. The proportion of Irish PPS issues fell from 38.7% in 2017 to 22% in 2022.

The population of the state was officially recorded in Census 2016 as 4,761,865 and 5,149,139 in Census 2022. That is an increase in population of 387,274.

Net migration over that period was officially estimated at 188,700. The natural increase in population was 172,000 so the two combined come to 360,700 which is not too different from the officially estimated population.

The problem is, as identified by Alan McSweeney and as referenced above to my analysis of all the official statistics related to inward migration, is that the latter consistently appear to give a much higher number of the people likely to be resident in the state than the official Census based estimate.

Is it actually credible that of the 115,306 persons born outside of the state who were issued with a new PPS number in 2017 that just around half were here long enough to be counted as among persons who had migrated to Ireland? Or that just 364,100 or 47% of the 771,813 issued with a PPS number between 2017 and 2022 stayed?

The Ukrainian influx is a factor but those numbers only account for a relatively small number of PPS issues and in any event as the years pass it is evident than a large proportion, if not most of the Ukrainians, intend to stay here for a long time and perhaps for good.

The questions regarding the discrepancies are accentuated when we have already seen that the number of people who came to live here in 2022 as calculated from other official sources very closely correlates to the number of PPS issued. Which suggests that McSweeney’s evidence regarding an overall under-estimate of the population might still hold.

Those disparities are also apparent when comparing PPS issues to the Census returns although McSweeney was counting citizens of states other than the Irish state rather than persons born overseas. The latter is a significantly larger figure and is overall a much greater figure as can be seen from the fact that Census 2022 showed that persons with other than Irish citizenship accounted for just 12% of the population compared to the more than one million or 20% of the population enumerated in 2022.

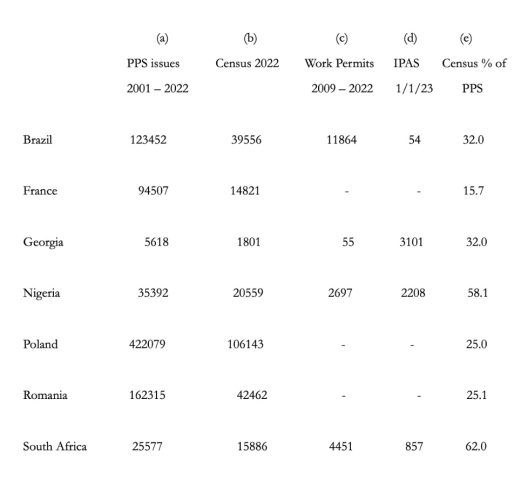

That can be illustrated with a number of examples which incorporate McSweeney’s Census 2016 and which I have extended to include PPS issues between 2017 and 2022 as well as birthplace statistics from Census 2022. The following table is a sample of a number of states including three of the main countries of origin of persons seeking asylum; Brazil as an example of a non-EU/EEA country, one western EU state whose citizens do not require a visa or a permit, and two eastern European countries which have become members of the EU during the period under review.

Poland and Romania are very different. Most Poles appear to have come here to work for specified periods and many have subsequently left Ireland. Romania is the country of origin for the large numbers of Roma here who have staggeringly high levels of unemployment and state dependency. 16,059 people identified themselves as Roma in Census 2022.

A year after the Census the Irish Times quoted a figure of 5,000 with no explanation as to why 11,000 people had pretended to be Roma a year previously, or why three quarters of them had gone home. Pavee Point which has taken upon itself to be the Roma’s representative here has also mentioned 5,000 prior to the Census. It is another indication of how little those paid to know these things actually know. What all agree is that unemployment among Roma is almost high enough to be described as full unemployment. One report put it at over 83%.

What the above figures show is that McSweeney’s calculation for non-nationals who came to Ireland and were issued with a PPS number compared to those who complete their Census forms with their citizenship is broadly confirmed by an updated analysis of the same data to 2022 with place of birth replacing citizenship as a more accurate indication of the size of the non-Irish born population.

The gap is partly explained by the number of persons who only stay in Ireland for a short period when they are employed. It is also partly explained as we have seen by the comparison between the CSO estimate of inward migration and the totals for work permits, students, asylum seekers etc that more people are certainly entering the country than appears to be acknowledged.

That led McSweeney to suggest that Census 2016 was lower by around 400,000 than what other statistics suggested was the population of the state. I see no reason to believe that a similar discrepancy does not exist between the overall population and that officially recorded in Census 2022. The exact scale of that discrepancy remains to be known.

What is certain is that the proportion of the population born overseas is above 20% now and is still growing. What is also clear – and even the revised population estimates from the CSO acknowledge this now – is that 90% of current and future population growth in the Irish state will comprise of immigrants and their Irish born children.