Two weeks after the 1923 GAA Congress which paved the way for that year’s final to go ahead on September 28, Kerry and Dublin first met in a challenge match, a month ahead of their final, in Tralee on August 24. Something that would be unthinkable in these times. Both teams were reported by The Kerryman to be “about to start training”, which again appears almost comical to modern eyes.

The challenge was advertised as ‘The Great Who Shall’. Admission would be one shilling and the referee was to be Jim Byrne, star of the Wexford four-in-a-row team. He was also to referee the All Ireland final. As it happened Byrne was unable to attend the match which was refereed instead by Tom Costelloe of Tralee.

‘P.J O’C’, The Kerryman GAA correspondent, looked forward to the match and warned that “When Dublin sends its best men to represent it it goes without saying that they will take some beating.” He dismissed rumours that Dublin only intended to field a “scrap team” and claimed that Kerry also would be putting out its All Ireland team.

On the day a crowd of around 6,000 packed into the Sports Field, yielding a gate of £285. It was reported that the conduct of the crowd had been good and this was regarded by The Kerryman as “a happy augury for the future good relations that we all hope will exist between the youths of the country.” But the Civil War was not far away. General Richard Mulcahy, who was Commander of the Free State Army, attended as did Kerry pro-Treaty TD Fionán Lynch. Austin Stack was also there. The Kerryman, perhaps allowing its enthusiasm for reconciliation get the better of it, declared that Mulcahy, who was hated by republicans, had been seen in “friendly conversation” with Humphrey ‘Free’ Murphy, O/C of the 1st Kerry Brigade, who had been released from the Curragh and who had been on the Kerry team that lost the1915 final to Wexford.

P.J O’C elsewhere admitted that this report was in error.

The Dublin team was treated with extravagant hospitality, being put up at the County Board’s expense in the Ashbourne Hotel and brought on a visit to Casement’s Fort near Ardfert on the morning of the match. Roger Casement had been captured at that location, then McKenna’s Fort, three days before the Easter Rising when he landed from a German submarine on Banna Strand. My late uncle Denis used to tell us of a Dublin supporter on Hill 16 who greeted the arrival of the lads from the Kingdom onto the field in the 1950s by declaring at the top of his voice: “Look at them now boys. The men who betrayed Roger Casement.”

The Dubs did not, however, reciprocate the warm welcome to Kerry on the field of play where P.J O’C claimed that they beat Kerry “pulling up”. Kerry did lead at half-time but Dublin’s hand-passing game exposed Kerry’s lack of fitness despite the efforts of a few players like Con Brosnan. Brosnan had been active in the IRA during the Tan War and served as an officer in the Free State army during the Civil War and later.

P.J did not like the Dublin style and claimed that the old Kerry team would not have stood for it. “Any one of the old Kerry team would burst that combination in five minutes, and have no talk about it either”. He also complained about the lack of discipline by some Kerry players who would not stay in their allotted positions, thus allowing the wily Dubs the opportunity to roam about, hand-passing and all that Fancy Dan sort of thing.

John Joe Sheehy had scored a goal for Kerry after 20 minutes and Joe Stynes, who was adjudged Dublin’s best player, forced a number of saves from the Kerry goalkeeper Denis Hurley. Exchanges were pretty tough but there were no complaints. “A Dublin man was knocked out … but soon resumed amid applause.” Stout fellow.

Kerry led by 1 – 1 to 0 – 2 at half time. Despite playing into the wind, Dublin had a goal scored by Frank Burke of UCD early in the second period. Burke had been in the GPO in Easter Week, 1916 and succeeded the executed Padraig Mac Piarais as headmaster at St. Enda’s after his release from Frongoch. Another passing movement that involved all of the Dublin forwards led to Stynes crashing the ball into the net. Kerry, despite tiring, rallied but Dublin’s defence held out for a 2 – 3 to 1 – 4 victory which was sportingly acclaimed by the home crowd.

The O’Tooles players had not travelled, possibly for political reasons, so the Dublin team only bore a slight resemblance to that which contested the final on September 28 and which had six of the county champions in its starting line-up. Of the Dublin team who played in Tralee, only five togged out for the final. One of those who was in Tralee but who missed out on the big day was Frank Shouldice who had won Dublin county championships in 1914 and 1915 with the Geraldines. He was more famous for having escaped from Usk Prison in Wales in January 1919. Frank and his brother Jack had been in the Four Courts in Easter week and both remained neutral during the ‘War of Brothers.’. The Kerry team featured eight of those who would play in the final.

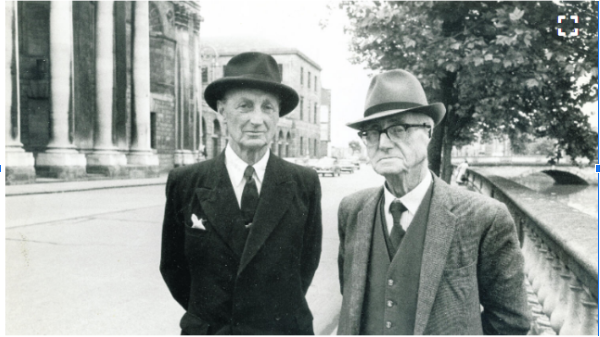

Frank and Jack Shouldice (Anglo Celt)

As the big day approached it was clear that interest in Kerry was huge and that the team was the focus of massive support. A large amount of money was collected to ensure that players would be reimbursed for attending training in the last few weeks. Training took place in Tralee under the supervision of Jerry Collins and appears mainly to have consisted of practice matches. They were reported as having shown improvement since the Dublin match and confirmed that by beating Cork in the 1924 Munster semi-final on September 7.

P.J O’C was also doing his best to stoke up the psychological stakes. He referred to a rumour that Dublin were not taking Kerry seriously and that they were putting it about that Kerry had refused to play in 1923, not because of the prisoners, but because they knew that they would have been beaten. “It is therefore up to our men to wipe out this implied insult.” Cunningly he also appealed to more than county pride. Alluding to Dublin’s “proud record” he contrasted their attitude to that of some Kerry players of whom, he claimed, “a good many fancy they have nothing else to learn about football and their presence in the field is enough to ensure victory.” Mick O’Dwyer would have had him in the dressing room for sure.

The Dublin newspapers, casting themselves as impartial ‘national observers’ reflected less well the feelings of the GAA followers. You get little sense from them of any great excitement in the city. In the week leading to the final the main story concerned the Boundary Commission that had been set up as part of the Treaty to adjudicate on disputed territory between the Free State and Northern Ireland. British members of the Commission had come to Dublin and Unionists were organising a mass campaign vowing to surrender ‘Not an Inch’ to Dublin.

News stories reflected the fact that the country was not “half settled” over a year after the end of the Civil War. There were regular crimes that would have been unthinkable a few years earlier, many of them involving guns. In one such two Northern Bank officials were held up by armed men near Moynalty in County Meath. One of whom wore a Free State Army uniform and brandished a service rifle and they made off with £1,200. Then there was the case of the 14 year-old Derry girl who was charged with “fraud.” This had consisted of her buying items for 2 or 3 old pence and then claiming that she had handed the shopkeeper two shillings. If disputed, she would create a scene. She told the court that she had spent the proceeds of her nefarious crimes on “the pictures and fish suppers.” A bould yoke.