On Tuesday, the ESRI published its annual report on migration and asylum in the Irish state. It was compiled by Keire Murphy and Anne Sheridan who work for the EU’s Migration Network here, which is partnered with the ERSI and is funded by the EU and the Department of Justice.

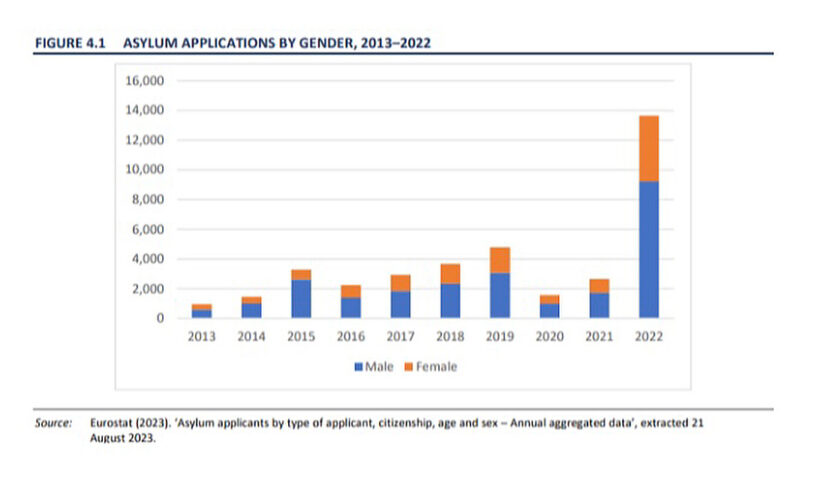

The report confirms that there has been a colossal increase in the number of people claiming asylum here, with 13,600 in 2022, a 415% increase from 2021 and a 186% increase from 2019.

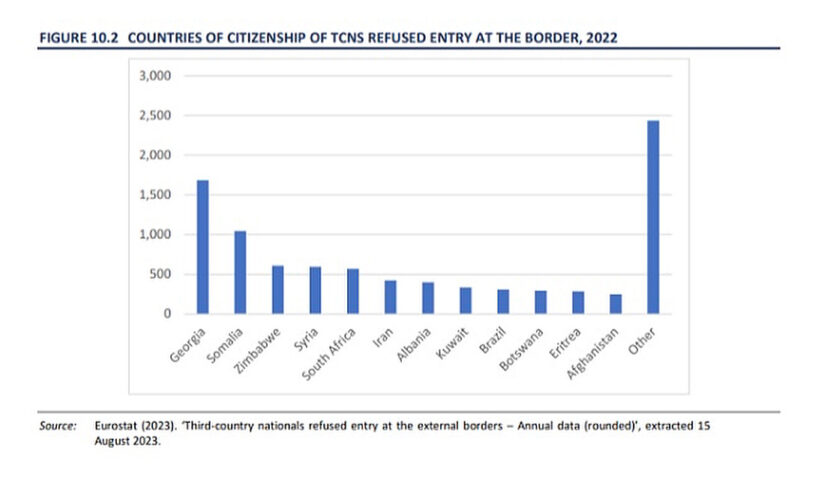

It also shows that the top countries of origin for applicants were Georgia (20%), Algeria (13%), Somalia (12%), Nigeria (8%), Zimbabwe (7%) and Afghanistan (6%).

The report notes the huge increase in the number of valid residence permits in 2022. This now stands at 234,057.

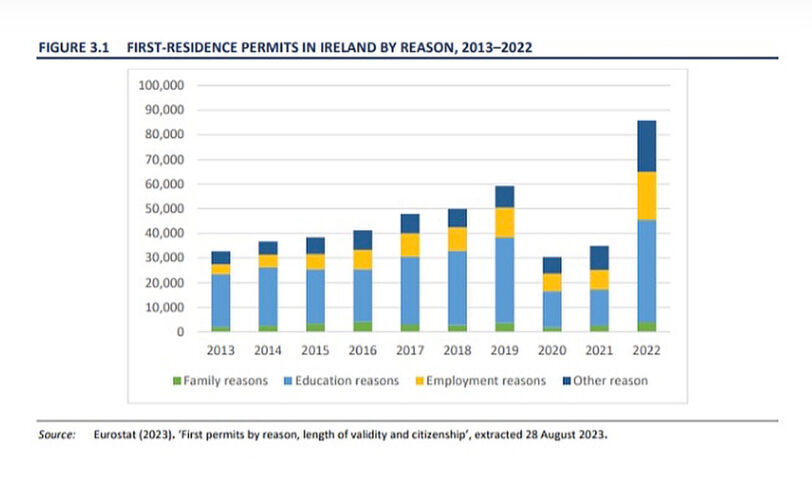

There were 85,793 first-residence permits issued in 2022 to legal migrants, compared to 34,935 in 2021. That represents a 146% increase on the number of permits issued.

As in previous years, education was the most common reason for permits – 48% of all permits in 2022, the ESRI says, followed by ‘other reasons’ (24%) and employment (23%).

That paints a rather different picture of migration into Ireland that was given by an Taoiseach in the Dáil this week, where he overwhelmingly connected it to work, and insisted it was therefore a positive factor.

9% of all residence permits granted for education in the EU were granted by the Irish state, which seems an extraordinarily high number.

Education accounts for 22% of all currently valid residence permits, and employment for just 27%.

That also undermines the argument that the massive level of immigration is a positive factor in public spending if just little more than one quarter are paying employment tax.

The report notes that the huge increase in the numbers of people seeking International Protection in the state led to doubts about the plans and timelines for the ending of Direct Provision as adopted in the 2021 white paper, and that this prompted a review by the Department of Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth (DCEDIY).

It also noted that the Department nonetheless pressed ahead with elements of the plan including the “acquisition of properties for vulnerable applicants” and “increasing state-owned accommodation property.” Which of course was and remains at the heart of the concerns expressed, and being expressed, by communities around the country and which were referred to by several TDs in the debate on the Dublin riots yesterday.

Interestingly, while they refer to efforts by the International Protection Office to speed up the processing of applicants, and to speedily determine their validity especially in relation to those arriving from “safe countries,” these efforts have encountered considerable opposition from the NGOs.

One of their criticisms was that the new procedures made it more difficult for applicants to “obtain legal advice prior to filling in the questionnaire.”

“NGOs also raised concerns about the new regulations for applicants from safe countries of origin,” the ESRI report says.

It would seem fair to ask how much of the substance of the applications that are made and which are subsequently rejected but then end up in lengthy appeals – especially when made by persons who have travelled here from both officially designated “safe countries of origin” and other countries where there are tenuous grounds for claiming asylum – is the product of “engagement” with the NGOs and the legal firms which they are in close contact with.

There are several references in the report to the state’s response to immigration, which of course has been overwhelmingly liberal, and has contributed to both the attraction of the Irish state for those coming here, and to the difficulties in dealing with the negative consequences where those arise. The report graphically illustrates that the concern expressed about the proportion of male migrants is statistically valid, whatever about any other criteria.

NGOs have complained about other areas than the more recent focus on possible bogus applications. The report notes that the African women’s NGO AkiDwa “raised issues” about the disproportionate numbers of children from ethnic minorities – presumably they are mostly referring to African children – who are involved in “childcare proceedings.”

They attribute this to “cultural misunderstandings” and the “lack of awareness of Irish law.”

There’s no clarity as to what they’re referring, but could prosecutions and concerns for FGM be considered by some a cultural misunderstanding?

The overall difficulty of any state agency attempting to address the evident difficulties is illustrated by the fact that the implementation of the White Paper on Direct Provision has largely been left to the NGOs to which that document “identifies as responsible for delivering wrap-around supports.”

However, as the numerous references, as above, in the report to NGOs consistently opposing any reform of the systems around migration prove, they are a negative influence when it comes to implementing a sustainable and publicly acceptable response to the crisis. Unless their role is severely curtailed, the problems identified in the report will never be properly addressed. The several references to specific cases also underline the barriers created by a cumbersome appeals process and a heavily invested legal advocacy.

A more productive approach is clearly refusing persons who present at port of entry with false or no documentation and no credible grounds for being in the state, is to refuse to allow them to enter. 9,240 people were refused leave to land here in 2022, and the breakdown of nationalities is largely in line with the overall proportions of people who do manage to make an application. Of course, being refused leave to land does not necessarily mean the person will be returned, a fact also illustrated by referenced case law.