Minister for Justice Helen McEntee has stated in response to a Parliamentary Question that “it is a priority of the Immigration Services to seek the removal or deportation of any person posing a threat to public safety or security.”

But she then admitted her department hasn’t kept data on the number of asylum seekers who have been deported from Ireland in recent years for having a criminal record either gained abroad or in Ireland.

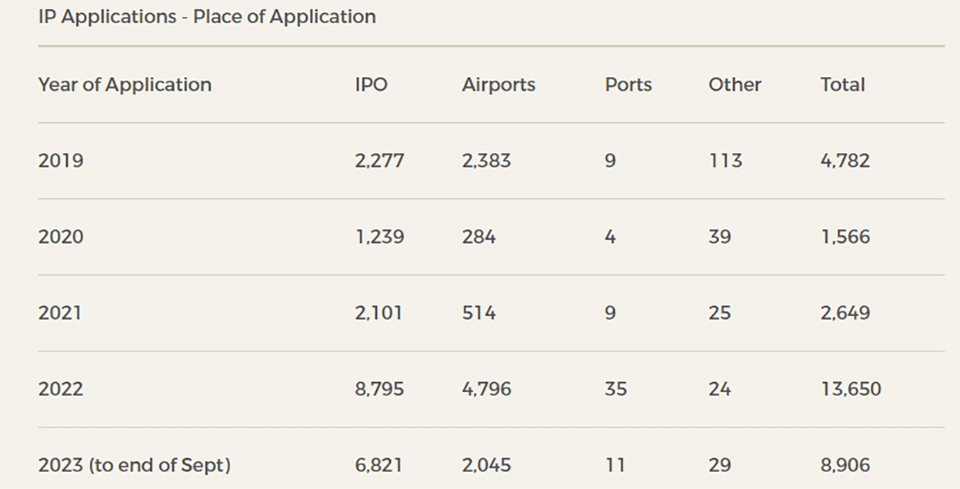

What was not discussed in depth was the revelation in the table supplied by the Minister – which, on inspection, shows that an enormous 77% of those claiming asylum in 2023 to date did so by turning up at the International Protection Office, instead at the airports or at a port or elsewhere.

It’s a statistic worth repeating: 77% of the people who claimed asylum in the state in 2023, first did so by arriving at the office where asylum claims are registered in Mount Street. The situation raises an obvious question, namely, how exactly did they get into the country to begin with?

Less than 23% of asylum claims were made at the airport, with another handful coming through the ports and elsewhere – which means the checks at entrance points upon which we are told we should rely for reassurance may be being avoided by large numbers of people.

In a newspaper report headed “State cracking down on international protection applicants who have committed crimes in other jurisdictions”, Minister McEntee is quoted as saying that:

“Each applicant has their fingerprint checked against the Eurodac system which allows officials to establish if the applicant has previously applied for international protection in another member state.”

However, Eurodac, according to the EU body EUR-Lex, “is an EU database that stores the fingerprints of international protection applicants or people who have crossed a border illegally.”

“The purpose of Eurodac is to give member states information to help them to decide which country is responsible for a person’s international protection application.”

In fact, EUR-Lex warns that Eurodac can only be used by police forces and the European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation to compare fingerprints linked to criminal investigations in very particular circumstances and as “only as a last resort.”

Furthermore, it states that “No Eurodac data may be shared with non-EU countries (other than Iceland and Norway)”.

It’s not the same as the False and Authentic Documents Online system (FADO) which European Border Agency, Frontex, claim can determine the validity of a document within seconds – and which could be used by serious countries to vet arrivals.

If McEntee has ordered that FADO be used in a ‘crackdown’ on criminals coming here and then claiming asylum, she didn’t say so.

Much was made of statements by the interim Justice Minister, Simon Harris, earlier this year that checks on migrants arriving without documents were being stepped up at Dublin Airport.

But what if most of the people claiming to be seeking asylum (while often arriving from safe countries like Georgia) are not actually claiming asylum at the airport at all, but turning up at the IPO office having already entered the country?

Neither did the Minister say if there were plans to correct the failing of the State and begin collecting data regarding the deportation of criminals who had come here to claim asylum – information which is surely in the best interests of Irish citizens and their safety.

MINISTER’S RESPONSE

The Minister was responding to a written question from Aontú leader Peadar Tóibín enquiring about the number of persons who have been processed by the asylum application system and have been discovered to have criminal convictions in other jurisdictions. He also wanted to know how many such applicants over the past five years have been deported due to such a record or having attained a criminal record here.

The Minister’s claim that there are no statistics detailing the number of such people also appears somewhat odd given that she had also stated that “Any and all criminal convictions are considered when processing an international protection application. An Garda Síochána notify the Department of matters which may be relevant to its examination of an application.”

Her response to other questions from Deputy Tóibín would also indicate that the claim the State is “cracking down” on “applicants who have committed crimes in other countries” does not seem to be exactly a full description of the situation as it stands, whatever about the Minister’s intent for the future.

She also clarified that “in relation to persons seeking international protection who have committed a crime outside the state, this may or may not be material to their international protection claim”.

Tóibín had also asked the Minister about the number of people who were claiming asylum in the state having crossed the border with Northern Ireland, and also the number of persons who have come to Ireland on student visas and holiday visas who subsequently applied for asylum.

McEntee said that there is no record of the numbers who have applied after “travelling over the land border”, nor it seems on “those applying who have been resident prior to making an application.”

So much for the rigour and cracking down and all.

The table she supplied (above) regarding where applications apply for International Protection does, however, provide the vital information referred to above – and may also indicate that some applicants may have crossed the border with the Six Counties and may therefore have been resident for at least some period in another jurisdiction where they ought to have made such an application. If that is indeed the case, those numbers have grown significantly since 2019.

In 2019, 48% of applications were made other than at airports or ports or other known locations.

That could also imply that some part of the 48% who directly applied to the International Protection Office were persons who had most likely entered the state over the border or by some other unknown means.

That percentage rose to 64% in 2022, and so far in 2023, has accounted for 77% of applications made for asylum directly to the International Protection Office.

That figure could also include people who had come here legitimately on student or holiday visas, and perhaps persons who had managed, despite all the supposedly rigorous checking at points of entry, to enter the country illegally and undetected and subsequently applied for asylum.

Or is it the case that the numbers include people who came here and were issued visas by the State, but then went on to claim asylum?

The Minister also confirmed that an applicant is not legally obliged to make an application at a designated port of entry.

It seems less like cracking down, and more like as making it up as you go along perhaps…