The most striking thing about the place names in the part of Tipperary around Upperchurch is the name of the village itself. At first glance it appears to be an example of one of the rare places in Ireland that were given an English name for a new settlement or as a replacement for an older name.

In fact, as can be seen from the English records, including the Cromwellian Civil Survey and the Down map of the 1650s, Upperchurch was then a transliteration of the original Irish place name An Teampall Uachtarach to Templeoughteragh, much as Luimneach became Limerick or Béal Feirste became Belfast.

Eventually, perhaps one of the forebears of the person who decided to name the shopping centre in Finglas as Clearwater decided to provide a literal translation – except more accurately in the case of An Teampall Uachtarach than Fionnghlas.

Down Survey Maps | The Down Survey Project (tcd.ie)

There are very few of what appear to be simple English place names around Upperchurch. As with Upperchurch itself, Dogstown appears to have been believed by the Ordnance Survey in 1840 to be an almost literal translation of Cnocán a’ Mhadradh and may even have been the translation chosen by themselves.

Another placename that was similarly translated was Cnoc a’ Chaisléain, now Castlehill but transliterated as Knockacashlane or similar from the 1570s up until the 1840s.

Transliteration was the approach most favoured by John O’Donovan who was instrumental in the Ordnance Survey of Ireland from 1830, and can be seen in most of the placenames in the area. Their objective of perhaps retaining the original meaning of placenames transliterated into English orthography failed, of course, as Irish as a living language died for the most part. Most transliterated place names from Irish sound like gibberish, even to people who can speak Irish.

How many people around Upperchurch 1901 knew what Shevry, where one of the RIC barracks was, or what Ballyboy or the deceptively Elizabethan Tudor sounding Carew meant? You will be glad to know, as I was, that Carew is not named for one of the butchers of the Desmond Rebellion and who unfortunately missed his proper end along with his brother at the hands of Fiach Mac Aodh at Gleann Molúra in 1580 when he was one of the hundreds of English to managed to run away.

Rather, Carew is a corruption of An Cheathrú, quarter, which might mean perhaps a quarter share of land, or quarters for soldiers. Shevry might originate in several root words. Its official designation is Seithe Bhreighe, which could refer to ‘hide,’ but O’Donovan himself seemed to favour Síodhbhruigh which would mean ‘fairy palace.’ Ballyboy can be a transliteration of several Irish placenames but the one preferred for the townland in Gortkelly is An Bealach Buí, the yellow road or pass.

Gleninchnaveigh is Gleann Inse na bhFia, the glen of the meadow of deer. A marshy meadow. Most of the townland names were similarly directly connected to their natural features, some of which have long disappeared as in boggy meadows of deer. My own ancestors, and now cousins, have lived for at least two hundred years near the top of Moher Hill.

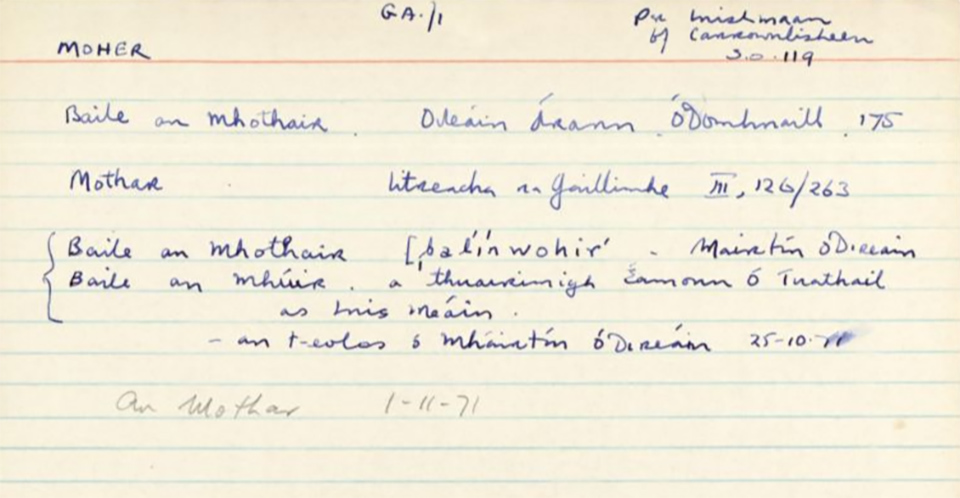

Most unromantically it is related to a thicket of trees or bushes, although in Munster Mothair apparently also referred to a ruined building, the sort that has been retaken by the scrub, I suppose. The great poet Máirtín Ó Direáin seems to have had another possible origin for the Moher found on Inis Meáin – Baile an Mhúir. The Tipp Moher is on the Cromwellian map.

Baile an Mhothair/Moher | logainm.ie

Were our people there? Who knows, probably not. One legend is that Treacys were originally in Úi Bhairrche, part of Carlow now and where there was a Treasach lord in the 800s. A later legend is that they were with Ó Neill at Cionn Sáile. And indeed there is a line of Treacys all the way along the trail after the defeat, through Tipp and east Galway right up to Treacys/Traceys in Fermanagh and Tyrone.

There is also Ballynahow – Baile na hAbha, which is happily defined on two sides by the mighty river Clodiagh. The river rises at the foot of An Comar, the meeting place, and not far from An Cnoc Fionn, the white mountain, or might it be a reference to Fionn? Probably not, no more than Fionnghlas.

Clodiagh is from An Chlóideach which seems to originate in a generic name for a mountain river or a stream, cláideach. It later joins the much more modest Farneybridge River, from fearna, alder tree, to become the An Sean Shruthán and eventually become part of the Suir near Clonoulty. An tSiúir being appropriately one of the ‘three sisters’ along with An Bhearú, the boiling water, and An Fheoir, grassy shore.

Sometimes the original name of a place can be ambiguous and convey very different notions of the past. During the Summer I heard people in Corca Dhuibhne wonder about the origin of Baile Loisce, close to Baile na nGall where Raidió na Gaeltachta is based. It comes from the word loisc associated with fire and burning. Perhaps some speculated it was to do with the nature of the land, being scorched by the sun.

Surely, though, the more likely derivation is from the local settlement having been put to the torch by the English, the Gall who succeeded the Viking Gall who named Smerwick.

The Tudor Gall laid waste to the locality during the Desmond Wars culminating in the betrayal and slaughter of the garrison at Ard na Caithne/Smerwick across the water from Baile na nGall in November 1580.

Likewise, Kileroe, Gortkelly in Tiobraid Árann. Roe is generally a transliteration of the Irish word for red, rua. The 1840s Ordnance Surveyors seemed to be leaning towards that, Coill Ruadh, but the official name of the townland is Coill Chró, the bloody wood, or even the wood of gore.

The 1654 Down Survey Keilcrow would seem to confirm this. Pallas, An Phailís, or palisade, is another echo of successive arrivals of foreign soldiers. The Latin root word for palisade, palus/stake, is the same as that for the Pale. The many Pallas around the country were forts of the invader men.

No matter where you are in Ireland you are walking among places that have names that once meant something. They were how the people had described where they lived and its relationship with the world around them, and the other people who were there and had been there, or who were part of their mythology and cosmic view of Creation.

Separating a people from that knowledge of themselves by removing their native tongue and all the lore associated with it is the most effective means of conquest – one known to all uninvited guests from the Tudor robber barons to the German and Russian colonisers of Poland.