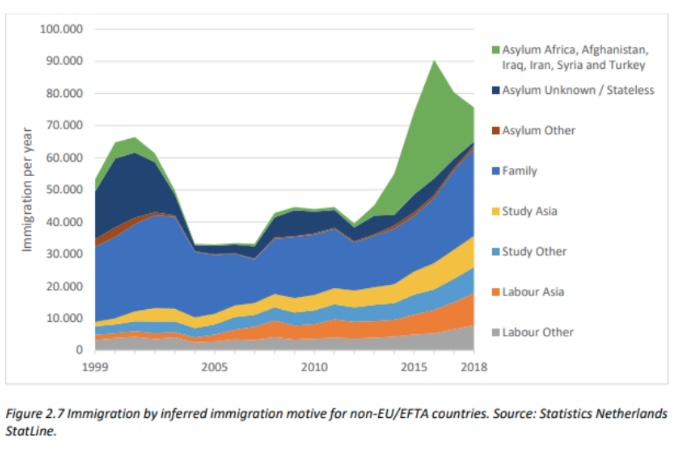

As reported on Gript yesterday, a migration study by Dutch economists at the University of Amsterdam shows the raw financial cost of immigration into the Netherlands. The study claims new arrivals cost Dutch taxpayers approximately €27 billion per annum, with all signs pointing to this amount rising to further, unsustainable levels in the coming years.

The study, titled “Borderless Welfare State”, was conducted by Dutch mathematician Dr. Jan H. van de Beek and it calculates the fiscal impact of mass immigration between 1995 to 2019.

Currently the Netherlands, a politically centrist European country, looks set to install a populist government led by right-wing PVV leader Geert Wilders following elections last November.

DUTCH DEMOGRAPHICS

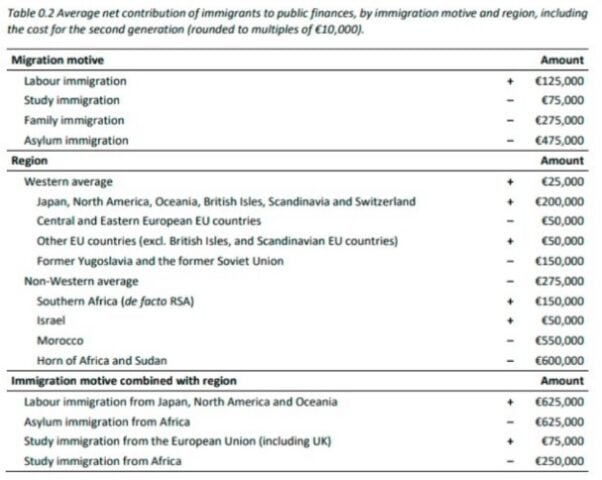

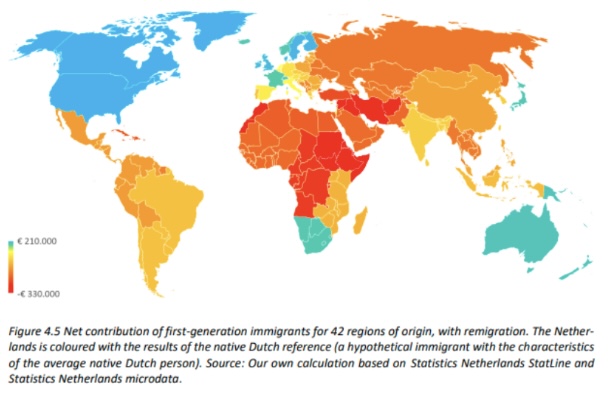

Differentiating between what it calls “Western” and “non-Western” immigration the study presents several possible scenarios for the demographic future of the Netherlands and its budgetary impact.

One of the more pessimistic timelines involves migration “remaining at current levels for a long period of time, with the current negative net contribution per immigrant” resulting in an annual cost of €50 billion euros before mid-century.

Immigration is one of the defining topics in Dutch politics with the normally stable Dutch government collapsing last summer over its handling of an asylum crisis and its negative effect on housing. The issue of longstanding Islamic extremism and narco-terrorism, primarily caused by the nation’s Moroccan and Turkish communities (with narco-terrosim emerging as a major threat to the Dutch state), has also become one of public concern.

According to the study 24% of the Dutch population are from first or second generation migrant backgrounds. The 17 million citizens of the Netherlands are dealing with a massive education and contributory gulf existing between European migrations and those from Africa or the Middle East.

The study was compiled using anonymised data from Dutch citizens in conjunction with the Dutch census office and aims to provide an in-depth multi-generational assessment on the changes as a consequence of mass immigration into the Netherlands.

The authors of the study note that the Dutch government ceased calculating the net impact of mass immigration in 2003 emphasising the fact that the “Netherlands is not sovereign when it comes to immigration” due to the role played by the UN and EU as well as a variety of transnational bodies.

It also documents how Dutch policymakers have yet to fully take into account the changes caused by mass immigration and argues that citizens will soon be forced to decide if they would rather end mass immigration or keep the current rates of welfare.

SOLUTIONS FOR FAILING POLICY

Van de Beek and his team conclude “continuing immigration with its current size and cost structure will put increasing pressure on public finances. Curtailment of the welfare state and/or immigration will then be inevitable.”

The study critiques the Dutch social welfare model of acting as a “reverse welfare magnet” incentivising migrants with criminal behaviour to remain in the country whilst economically productive migrants leave the country after a period. The study also warns that rates of population growth in Africa and the Middle East make the current Dutch asylum strategy unsustainable with refugees a fiscal timebomb for the country to deal with.

It is also quick to shoot down the concept of immigration solving Dutch demographics stating “on average, the fertility of immigrants is below the replacement level as well, partly because immigrants from high-fertility groups adjust their fertility downwards over time.”

After presenting a multivariate statistical analysis about the net contributions made by various migrant groups, and the impacts of factors such as education and crime, the report comes to the stark conclusion that “open borders and a welfare state do not go together” declaring that mass immigration is on track to upend the current Dutch social democracy.

The Dutch are not the only European social democracy to feel the intense strain of demographic change Sweden, formerly regarded as a bastion of liberal democracy, is turning its back on certain aspects of mass migration as its government vows to protect the welfare state by curtailing non-EU migration.

OPPORTUNITY AND OPTIMISM

While the report highlights the shortcomings of failing immigration policies as a solution to declining fertility and overall national stability, there are many optimistic comments that emphasise the urgency faced in many western nations to off-set ageing populations.

Some years ago, Deutsche Bank chief economist David Folkerts-Landau commented that new migrants could “strengthen Germany’s economic position globally as well as in Europe over the coming decade”. Folkerts-Landau estimated that the newcomers could “easily” make up some 10 percent of the country’s population by 2025 and would be necessary in dealing with the ageing population. 18% of people in Germany are foreign born at present. Unforeseen migrations since 2015 included the Ukrainian refugee crisis, where Germany took in 1.1 million people fleeing war.

With rising migration levels and current and imminent large-scale wars, European nations reviewing and reforming their migration and refugee programs will be paramount to ensure successful integration and societal stability.