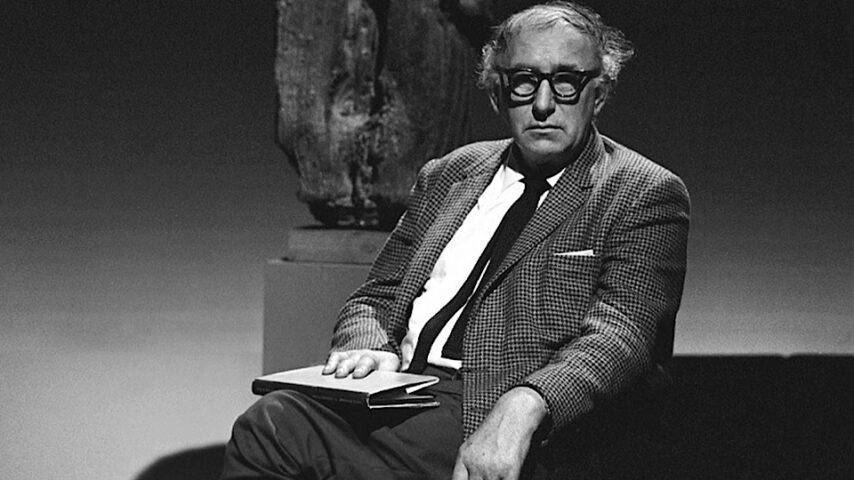

Today, November 30th, marks 55 years since the death of Monaghan-born poet and novelist Patrick Kavanagh, one of Ireland’s most iconic writers.

More than 50 years on from his death, the poet is still remembered and celebrated for various reasons, and his appeal endures to this day – with his writing particularly memorable for an ability to recount Irish life so vividly through the lens of the everyday.

Some of Kavanagh’s most famous works include the once-banned poem ‘The Great Hunger,’ ‘On Raglan Road,’ and his semi-autobiographical novel Tarry Flynn.

Kavanagh, the son of a shoemaker and farmer, was born in the rural townland of Inniskeen, in the border county of Monaghan in October, 1904. He was the fourth of ten children. His brother Peter would go on to become a university professor and writer, while two of his sisters became teachers, three became nurses, and one became a nun.

He described his father, James, as “a shoemaker, small farmer, hob doctor and ditto lawyer’. The family farm was less than forty acres, and it was here Kavanagh would spend the first 35 years of his life, before he moved to Dublin in 1939.

It was in the rural family home filled with the hustle and bustle of shoe-making, pig-keeping, and young children where one of Ireland’s greatest poets began to write. Throughout his life, Kavanagh maintained a passionate attachment to and affection for his birthplace, something consistently palpable in his writing.

“There are several fields I long to see again,” he penned later in his life. The best of Kavanagh’s poetry and prose recounted simple childhood memories in vivid, captivating detail, evoking images of his birthplace, ditches, and crossroads.

Kavanagh’s ‘A Christmas Childhood’ remains the most quoted Christmas poem in Ireland to this day. The poem, which he wrote while he spent a Christmas alone in his flat in Dublin, turns back time to the magical winters of his childhood, and was born out of his loneliness and solitude as an adult.

The Christmas favourite is emotional and nostalgic for rural, farming, and family, as Kavanagh, in his adult isolation, recounts warm, bright memories of family life, which come to the reader through the Christian imagery of the story of the nativity of Jesus at Bethlehem. The poem also evidences Kavanagh’s Christian spirituality, and his belief in the incarnation – with the poet believing the birth of Christ has both personal and universal significance.

Kavanagh left school when he was just thirteen, to follow his father into the family shoe making business. He took up farming after that, and earned a meagre living for a number of years.

He was still working as a farmer when his first volume, ‘Ploughman and other Poems’ was published in 1936. His work as a farmer coloured much of his work, conveying with grittiness the tough reality of life on the land, such as in ‘Stony Grey Soil’ where he writes: ‘You clogged the feet of my boyhood’. The Great Hunger, perhaps his most famous work, written in 1942, also details the realities of subsistence farming in Monaghan.

Throughout his writings, Kavanagh continually takes inspiration and consolation from nature, and in memories made in Monaghan, which are retold with beauty, fondness, and love.

Amidst a backdrop of hard-pressed times, financial struggle, claustrophobia, and fierce hardship in Ireland, Kavanagh would often feel isolated as a poet — on the margins of society, with a lot of his lifetime marked with financial difficulty. A lot of his poetry shines a light on Kavanagh’s soul questions and the inner conflict he experienced.

The outbreak of World War II had a damaging impact on the careers of emerging Irish writers at the time, including Kavanagh. He, alongside the likes of Flann O’Brien, lost access to their publishers in London – and reprints of their books couldn’t be arranged. During this time, smuggling opportunities on the border, especially in Monaghan, proved more of a lucrative offer than writing.

He became a hesitant city dweller when he came to Dublin in 1939 and remained there for the remainder of his life.

John Nemo, in his biography, details Kavanagh’s encounter with the literary world of the capital. He writes that: “He realised that the stimulating environment he had imagined was little different from the petty and ignorant world he had left. He soon saw through the literary masks many Dublin writers wore to affect an air of artistic sophistication. To him such men were dandies, journalists, and civil servants playing at art.

“His disgust was deepened by the fact that he was treated as the literate peasant he had been rather than as the highly talented poet he believed he was in the process of becoming”.

Much of the poetry he wrote and published when he settled in Dublin offers an implicit critique of nationalism and the ideals of the Revival.

It was in 1942 that he published his long poem,‘The Great Hunger’ which detailed the struggle and hardship of the rural life Kavanagh knew so well. The poem, penned from the perspective of a solitary peasant during times of famine and emotional turmoil, is often regarded by critics as Kavanagh’s finest work of all.

It was published in British literary magazine ‘Horizon’, and was brought out as a Cuala Press pamphlet by Frank O’Connor that same year. Rumours abound at the time that all copies of Horizon were seized by the Garda Síochána, Kavanagh denied this had happened. He said later that he was visited by two Gardaí at his home – most likely in connection with an investigation of Horizon under the Special Powers Act.

When he lived in Dublin, he launched his own journal, ‘Kavanagh’s Weekly’ and worked part-time as a journalist, writing a gossip column in the Irish Press under the pseudonym Piers Plowman from 1942 to 1944, also writing as a film critic for the same publication from 1945 to 1949. In 1946, then Archbishop of Dublin, John Charles McQuaid, found the poet a job on the Catholic magazine, The Standard. The Archbishop would continue to be a friend to Kavanagh throughout his life.

Kavanagh worked as a journalist in Belfast in late 1946, and in the aftermath of World War II, when jobs were scarce, also worked as a barman in a number of public houses in the Falls Road area after moving to the city. He returned to Dublin in November 1949.

In 1954, he suffered from cancer – and underwent surgery to have a lung removed. Remarkably, Kavanagh survived lung cancer, even though the odds were so slim. His incredible recovery gave him a new appreciation for being alive, and sitting by the “leafy-with-love banks” of the grand canal in Dublin. redemptive healing washed over him.

Sitting by the Grand Canal in Dublin following his operation, Kavanagh said of that moment that he had found his poetic voice again, writing: “As a poet I was born in or about 1955, the place of my birth being the banks of the Grand Canal ”. There is a statue of Kavanagh erected by the canal to mark the spot where he sat, inspired by ‘Lines Written on a Seat on the Grand Canal, Dublin’.

His Catholic faith also took on a new meaning to him later in his life, and his poetry took on a mystical vision. His poetry makes it clear that he welcomes a more life-embracing God, who was not deterred by human failure.

By this stage, Kavanagh’s faith had been tested and deepened after he had battled with many demons, and after enduring great suffering, he had learned self-forgiveness and self-acceptance, giving him a sense of surrender to life.

In his poetry, Kavanagh’s spirituality has a depth and an integrity that makes it clear God can be found in all human experience, in nature, and in everyday beauty. Indeed, writing as a peasant poet, the clay itself took on a powerful metaphor for Kavanagh’s own life; afflicted, yet fruitful. To Kavanagh, Heaven, something mysterious in his earlier life, became visible in brighter moments, in the beauty of autumn leaves, and in the things of the everyday that we take for granted.

Kavanagh’s genuine, mature spirituality was made evident in his gratitude, because whatever happened in a life of twists and turns, he was grateful. He gave thanks for life.

In later life, Kavanagh was also described as somewhat as an idealist, and he also struggled with drink as his health worsened. He was often spotted, a rather dishevelled figure, frequenting the bars of Dublin — and was known for his love of whiskey and falling out with friends and acquaintances.

In April 1967, Kavanagh wed his long-term friend Katherine Barry Moloney, a niece of Kevin Barry, and they set up home together on the Waterloo Road in Dublin.

He died on November 30, 1967 in Merrion Nursing Home in Dublin, shortly after falling ill at the first performance of a play adaptation of Kavanagh’s semi-autobiographical novel Tarry Flynn at the Abbey Theatre.

He is buried in his native Inniskeen, alongside his wife, who died in 1989. His grave is adjoined by the Patrick Kavanagh Centre, a popular interpretive visitor centre dedicated to his life and work.

His poetry, recalling Irish life in the early 20th century, is timeless, and its appeal still endures. This was evidenced, when, in 2000, The Irish Times compiled the nation’s favourite Irish poems – and ten of Kavanagh’s featured in the top 50.

He is widely regarded as the second most popular and renowned Irish poet after W.B. Yeats, and the late Seamus Heaney spoke of Kavanagh’s influence on his own work. Kavanagh was also groundbreaking in the sense that he heralded in a new era of Irish poetry and pathed the way for others from poorer, working backgrounds to join the profession. He was a revolution for his time, seeing as normal people did not write poetry for a living. Yet Kavanagh, far from being part of Ireland’s elite class, rose against the odds to become one of the greatest Irish poets of his generation.

Nobel Laureate Heaney, said that Kavanagh’s poetry “had a transformative effect on the general culture and liberated the gifts of the poetic generations who came after him”. Both shared a belief that the local or parochial mirrored the universal. Kavanagh once said that: “All great civilizations are based on the parish”.

Fans of Kavanagh’s include New Zealand-born screen actor Russell Crowe, who says he likes “how [Kavanagh] combines the kind of mystic into really clear, evocative work that can make you glad you are alive.”

In February of this year, after winning a BAFTA for his leading performance in A Beautiful Mind, Crowe quoted a four-line poem from Kavanagh during his acceptance speech:

“To be a poet and not know the trade,

To be a lover and repel all women;

Twin ironies by which great saints are made,

The agonising pincer-jaws of heaven.”

His legacy also lives on through The Patrick Kavanagh Poetry Award, which is presented each year for an unpublished collection of poems, taking place each September in Inniskeen.