As Eamonn Dunphy the former soccer pundit might have put it – as he did when assessing the Association Football prowess of the French boy Michel Platini – “Storm Éowyn was a good storm but not a great storm.”

(With apologies to anyone who suffered because of it through power cuts and so on, including my own daughter who will not be in the least amused if she reads this…)

Storm Éowyn was apparently named after one of the minor characters in The Lord of the Rings. Tolkien is believed to have derived the name etymologically from the word ‘eoh’ for horse. (Thank you Sophie Clarke of The Irish News for that nugget.) My own contribution to that is to note the passing similarity between the word ‘eoh’ and the old Irish for horse: ‘ech’ or ‘each.’

References have also been made by way of comparison of Storm Éowyn to Óiche na Gaoithe Móire/The Night of the Big Wind that struck Ireland on January 6, 1839.

There is a very good account of this in a paper by Lisa Shields and Denis Fitzgerald published in 1989 by Irish Geography. They looked at newspaper and official sources as well as the Irish Folklore Commission and seemed to settle on the number of deaths at less than 300. Others claimed that thousands had died.

Lots of damage was done to dwellings, many of which were either very badly constructed or were very old, especially in the big towns. Dorset Street in Dublin was reported to have been particularly badly hit, and another estimate claimed that up to a quarter of the houses in the north city and county were badly damaged or destroyed.

It was also claimed that the waves on the west coast caused by the incoming storm came over the top of the Cliffs of Moher.

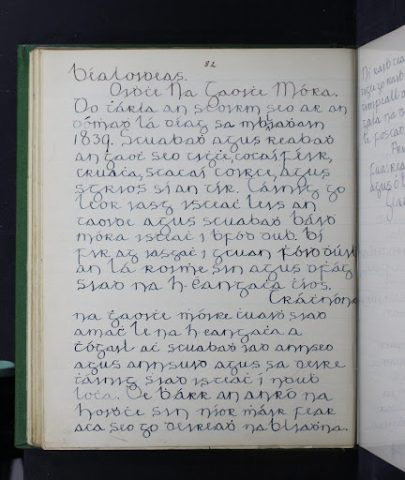

Shields and Fitzgerald did look at some of the Folklore Commission archives and they referenced two Irish language pieces on the great storm. Proinsias Ní Dhorchaí’s Clár Achreidh na Gaoithe Móire contains some references to the storm in songs from east Galway when it was still largely Irish-speaking.

It is much easier now to find accounts through the excellent search facility on the Dúchas site from UCD where the archives are held.

Tá sé de shaoirse agam dul i ngleic le cuid acu seo chun léargas a thabhairt ar an méid a d’fhulaing ár sinsir le linn Rabhaidh Dearg Eanáir 1839. Níl an cuntas thíos comhaimseartha ach ó búnscoil An Sáilín, Iorruis, i 1938. Dár leis an ngasúr gur chuaigh na hiascairí croga amach leis a eagnacha ach bhí orthu tháinig ar ais agus “De bharr an anró na hoíche sin níor mhair fear acu seo go ndeireadh na bliana.”

Oíche na Gaoithe Móire · Cill Mhór Iorruis · The Schools’ Collection | dúchas.ie

Tá an chuid is mó de na scéalta sa chnuasach as Béarla, ach tá roinnt bheag ó na daltaí scoile agus daoine níos aosta ó na Gaeltachtaí agus na mBreac Gaeltachtaí. Eachtraigh paiste scoile i Sráid na Cathrach, Co, An Chláir, scéal scanrúil faoi ‘An Doineann.’

Eachtra uafásach gan dabht, mar is léir:

Deireann na sean daoine gurb Oidhche Nodlag Bheug 1839 a bhí ann. An oidhche sin deirtear gur leag an ghaoith na tighthe go léir ins gach áit. Chuir sé sgannradh ar na daoine idir óg agus aosta. Fuair a lán des na sean daoine bás an oidhche sin leis an sgannradh cois na teine ag éisteach leis an gaoth gear cruaidh a bhí ag séideadh, mór thimcheall an tighe. Bhí na daoine ag bailiu gach rud mór thimcheall cun an gaoth do coiméad amach ach do theip ortha.

In the above, it is claimed that all of the houses everywhere were destroyed, and that lots of old people died just from the fright of listening to the wind howling about their homes. In another account in Irish from Achill, however, it was almost dismissed as a minor event. (Sounds like one of the Mayo football optimists I know who shall be hovering about Gills tomorrow evening after another spanking.)

In one of the English language accounts from a school child in Kesh, County Sligo, it was said that in later years when old people were applying for their old age pension and had to provide proof of age some of them would say “Oh I was such an age in the year of the Great Wind.”

In the village of Killan in Donegal The Night of the Great Wind was remembered as The Madoles’ Night as it was a night on which all members of a family of that name died, presumably when their home collapsed during the storm. In another community a young child provided almost an Old Testament account of the awful night “almost a hundred years ago,” one that would not be out of place in one of Cormac McCarthy’s sparse grim novels:

The sky was red before the storm came. It lasted twelve hours. There was great damage caused to houses stock and woods. There was no thunder or lightening. There was heavy rain that night. The fields were flooded and the crops were destroyed.

There are other accounts that had survived into the more recent memory of our people from times which the children in the late 1930s most likely heard about from grandparents and perhaps parents who had witnessed them.

Among them were big storms in 1890 and in 1903 and one from 1888 which was remembered by some as ‘Parnell’s Storm’ because it had taken place on the night of a great Plan of Campaign meeting in Roscommon town addressed by Charles Stewart Parnell on October 2 that year.

How many children now would be able to provide an account, in either Irish or English, of an event that had taken place almost a century before they were born? How many children in 2125 will be recounting the Terrible Night of Storm Éoywn? Not many I suspect.