Not alone do the current official estimates for future population growth come with heavy caveats because they have been proven to be markedly wrong even over a short period, but the entire basis for estimating the current population has been called into question.

This struck me over the last several years when comparing Census figures to other official statistics on the issuing of Personal Public Service (PPS) numbers and on work permits, asylum applications, citizenship and so on.

There is no single explanation for why these discrepancies exist. It is the case that some of the people who have been issued with a PPS number here for purposes of work will not stay in Ireland but will return home. That was particularly true of Poles and other citizens of what were once referred to as the “accession states”, large numbers of whom came to work and live in Ireland during the so-called Celtic Tiger years.

There is also perhaps an element whereby persons living here manage to avoid any unnecessary contact with the state, which may well avoid not completing Census forms, a not entirely difficult thing to do. There is, of course, little means to estimate the exact extent of this. I was told by the CSO last year that there had been 1,770,138 Census forms issued to private households in 2022 but they had no information on the numbers of returns. A returned form might also not be accurate if persons in a household chose to not enter details or to enter false details.

However, I was intrigued to come across an academic statistical research paper published in 2019 which highlighted the very same discrepancies. Not only that but the author of the paper, ‘Estimating the Size of the Irish Population,’ Alan McSweeney concluded that due to the inconsistencies mostly around the level of inward migration that “it may well be that the population is greater than that counted by the CSO in the census.”

It is a comment in itself upon the whole area of Irish demographics that McSweeney refers twice in his introduction to the “sensitive and emotive” nature of dealing with the statistical facts around immigration. It is to his credit, therefore, that unlike one has to assume a whole raft of statisticians, academics and allegedly informed commentators who have either ignored this, or worse have deliberately concealed or distorted what evidence there is, that he conducted such an analysis.

Gript has not been among such a sorry crew and I intend to reveal in further analysis how McSweeney’s research methodology can be applied to the more recent statistics which we have at our disposal, particularly bearing in mind that McSweeney’s key reference points such as Census 2016 date back quite a number of years and that the upward trend of inward migration has accelerated in the intervening period.

McSweeney based his research on evidence pertaining to the 18-66 age cohort as the Census population figure here ought to correspond roughly to the total for those in receipt of social welfare payments, education grants, who are in third level education and who are paying income tax and therefore part of the active workforce. He selected PPS issues as a reliable and rigorously monitored source of population data.

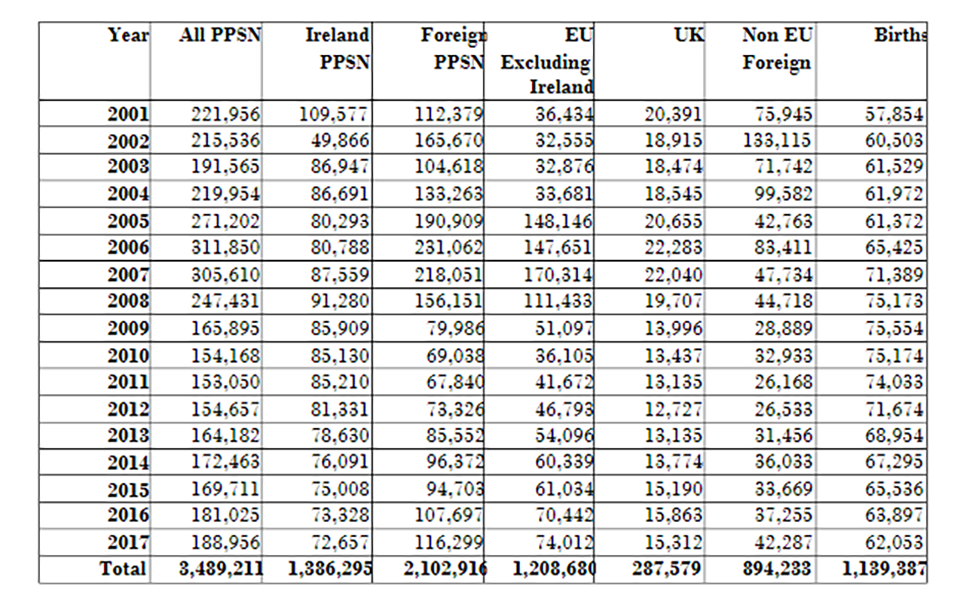

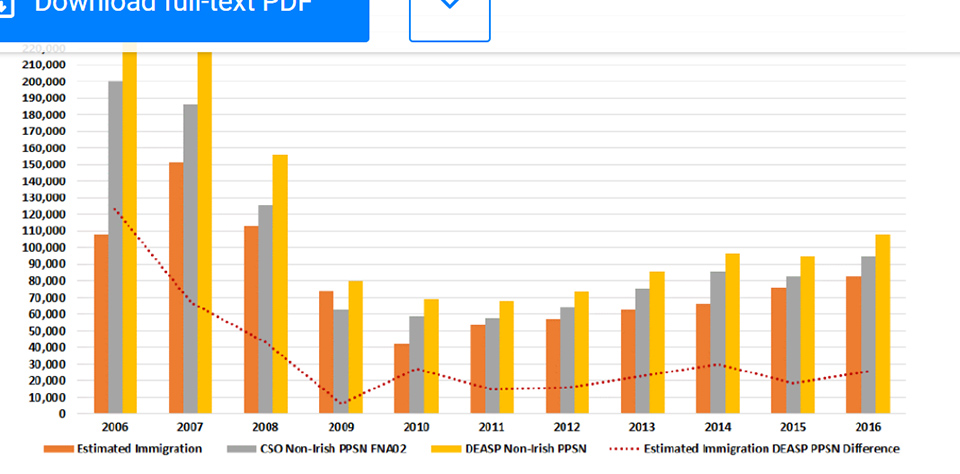

In comparing the PPS figures from both the Department of Social Protection and the CSO PPS statistics (which showed a 20% gap between the lower CSO figure and the DSP) to the CSO estimate for immigration, McSweeney found large discrepancies between the PPS figures and the estimates of the level of immigration. As shown in the following table.

The 2016 Census similarly showed huge gaps between the numbers enumerated as from different countries and the numbers of PPSN issues to persons from those countries. The following table contains a sample which includes both citizens of countries which are or were in EU (UK pre Brexit) and third countries which required permission to remain.

| Census 2016 | PPS | Census as % of PPS | |

| Afghanistan

|

1272 | 2489 | 51.3 |

| Algeria

|

595 | 1785 | 33.3 |

| Brazil

|

13640 | 62992 | 21.6 |

| Germany

|

11531 | 46069 | 25.0 |

| Nigeria

|

6084 | 26819 | 22.7 |

| Poland

|

122515 | 391185 | 31.3 |

| UK

|

103113 | 190196 | 54.21 |

What the figure would suggest is that the numbers of persons from outside of Ireland living in the state in 2016 was significantly higher than estimated by the CSO, even allowing for persons coming here from countries like Poland who might have worked here for a short period and then returned home.

There is no such explanation for the discrepancy between the numbers issued with PPS numbers from outside of the EU and generally to persons claiming asylum and the numbers who identified themselves as being of those nationalities in Census 2016. A PPS number is, of course, essential and is issued to all applicants for asylum and to work permit holders. There is no such benefit in filling in a Census form, to put it baldly.

The CSO, as McSweeney notes, themselves had to revise their population estimates because Census 2016 showed that they had under-estimated the population by 88,165. They also increased their estimate for immigration between 2012 and 2016 to 26,800. They revised their estimates of net migration for that period by 66,400.

The comparison of the PPS numbers to the Census and other figures would suggest that their under-estimate was much greater than that. McSweeney states that the CSO under-estimated the numbers of persons who migrated to Ireland between 2001 and 2017 by 160,000. You begin to wonder how reliable any of their population statistics are.

McSweeney also looks at income tax statistics and those for unemployment. His conclusion is that based on his analysis and the metrics used and comparing his figures gathered from the relevant sources to the baseline he had chosen that the population of the state in 2016 was under-estimated by 405,868.

He also makes clear in a footnote that a growing proportion of population growth was driven by immigration. As he also noted, the bald statistical extent of this was greater as “immigrants themselves contribute to the birth rate.”

McSweeney is quite clear that “issues with determining the extent of immigration …. Creates an issue with the size of the population of Ireland.” It is that which informs his conclusion that it is quite possible that “the population of Ireland is greater than that counted by the CSO in the census.”

Which raises all manner of questions. I personally am not in the least surprised and would expect that further analysis will show that the gap between the officially enumerated population and estimates, and the actual numbers living here are now in excess of those estimated by McSweeney. More of which anon.