One of the thornier questions regarding asylum claims in the EU is how the Dublin III Regulations are enforced, or indeed if they are enforced.

Dublin III came into force in 2013 and is meant to lay down “the criteria and mechanisms for determining the Member State responsible for examining an application for international protection lodged in one of the Member States by a third-country national or a stateless person (‘the Member State responsible’).”

The original Dublin Regulations from 1990 were meant to ensure that a person claiming asylum within the EU states that were signatories would have to make their application in the state in which they initially arrived. That basic principle is still meant to be observed but such is the scale of asylum seeking and illegal immigration that it has been rendered to a large extent ineffective.

A Freedom of Information request has elicited some interesting statistics about how the provisions under Dublin III are implemented here.

The FOI asked the Department of Justice for the number of letters sent to persons asking them to present to the International Protection Office in relation to transfers in line with Dublin III regulations.

The persons in receipt of such letters would likely be the subject of transfer because another member state had responsibility for their application.

The practice of arriving into an EU country and then travelling to another, perhaps because of a perception that conditions or benefits are more favourable, has been described as asylum shopping.

The Department stated that there had been 666 such letters in total sent between the beginning of 2020 and December 20, 2023.

The figures show that the number of requests sent to people to present themselves declined sharply from 451 in 2020, to 82 in 2021, just 31 in 2022, before increasing last year to 92. As we shall see, those figures bear little relation to the numbers who were actually transferred under Dublin III.

Consider the 92 requests made by the International Protection Office in 2023. Then contrast it to the response to a written question on December 5 last, the Minister for Justice, Helen McEntee, in which she said that there had been just two transfers under Dublin III regulations in the whole of 2023 to that date.

On January 24 this year the Minister was asked by Clare TD Michael McNamara to state “how many “take back” requests pursuant to the Dublin III Regulation were made within time in 2023 to which no reply was received, to which member states the said requests were made.” Minister McEntee replied that the information was currently being compiled.

How the transfer system under Dublin III operates, like many things connected to the asylum sector here, demonstrates that it has little teeth. When Oonagh McPhilips, General Secretary of the Department of Justice, appeared before the Committee of Public Accounts last May, she referred to Dublin III in the context of deportations.

Having first intoned the Five Sorrowful Mysteries of Self Deportation – “People do self-deport, and lots of people self-deport and do not tell us about it, so we do not know that figure – it is an unknowable figure.” – she stated that in relation to the total of deportations in 2022, that “a number of people had been transferred under the Dublin III Convention.” Such transfers are not, however, technically considered to be deportations.

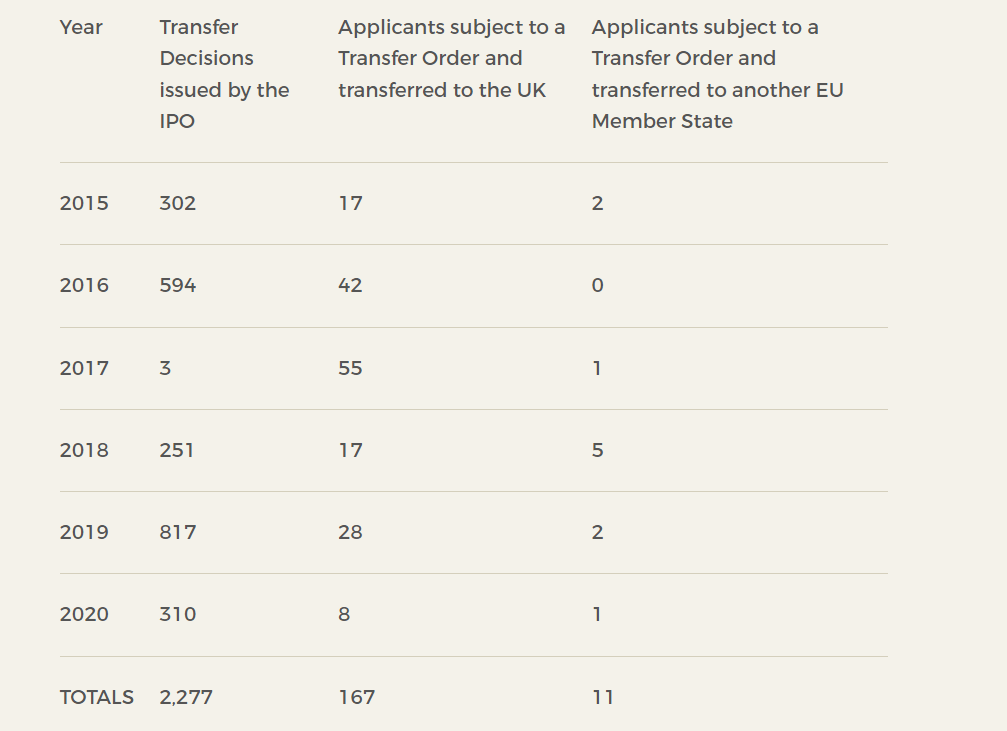

In a written response of March 31, 2021, Minister McEntee said that there had been 167 transfers to the UK under Dublin III between 2015 and 2020. There had been just 11 such transfers made to other EU states. The UK figure illustrates the extent to which persons apply first for asylum there before opportunistically entering a subsequent application in Ireland.

It should be noted too, that it is no longer possible to transfer people back to the UK as this ended with the UK’s withdrawal from the EU.

In December 2020 this led to Sinn Féin TD Louise O’Reilly claiming that there was a “an apparent rush in deportations under the Dublin III Convention” prior to the UK’s formal departure. Her authority for this was Dr. Lucy Michael, an “expert in integration.” The figure of 8 transfers under Dublin III to the UK in 2020 would give the lie to that. Where are all the experts on misinformation when you need them?

We have referred previously to some notable instances of that which led to the rejection of applications and of subsequent appeals, but the applicant was either given leave to remain anyway, or just decided to stay.

The sheer scale of the weakness of the application of Dubin III here is in any event illustrated by the fact that of 2,277 transfer decisions issued by the International Protection Office between 2015 and 2020, that just 178 or less than 8% ended in the person being transferred to another EU member state.

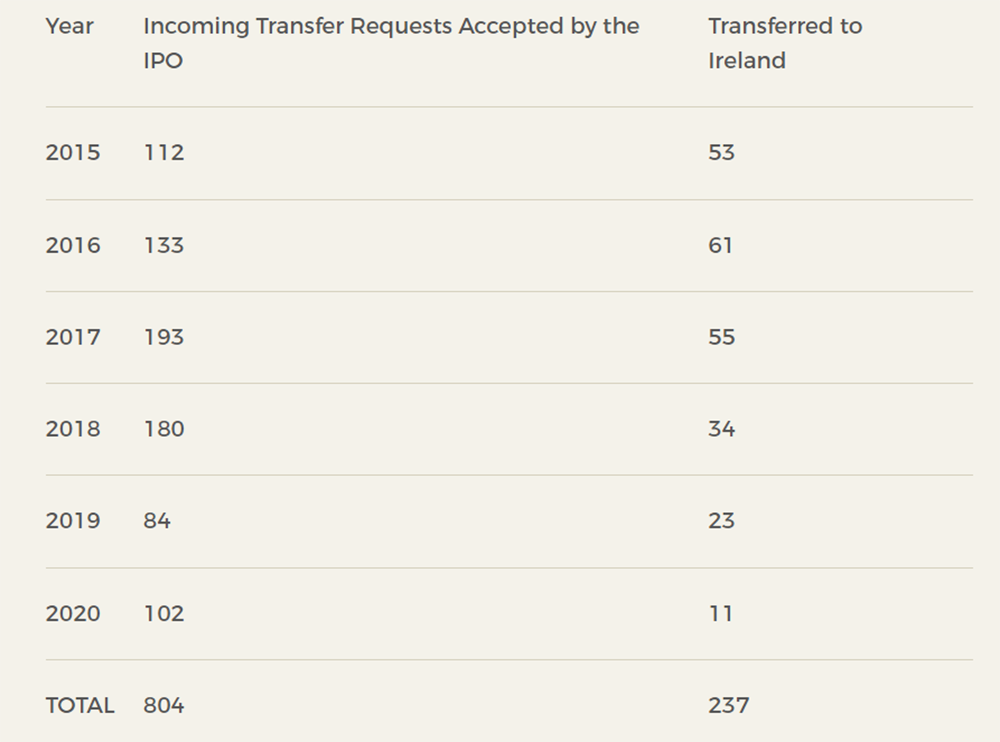

By contrast, when other EU states applied to have persons transferred to Ireland under Dublin III that resulted in 237 persons being transferred here over the same time period.

So, ironically, and despite the fact that Ireland is geographically the most difficult of EU states to enter, we took in more people under Dublin III transfers than we sent back to where they were adjudged to have made their initial application.

The International Protection Office here was also far more promiscuous in its adjudication of the requests made by other EU states as of a total of 804 transfer requests, 30% appear to have resulted in transfers.

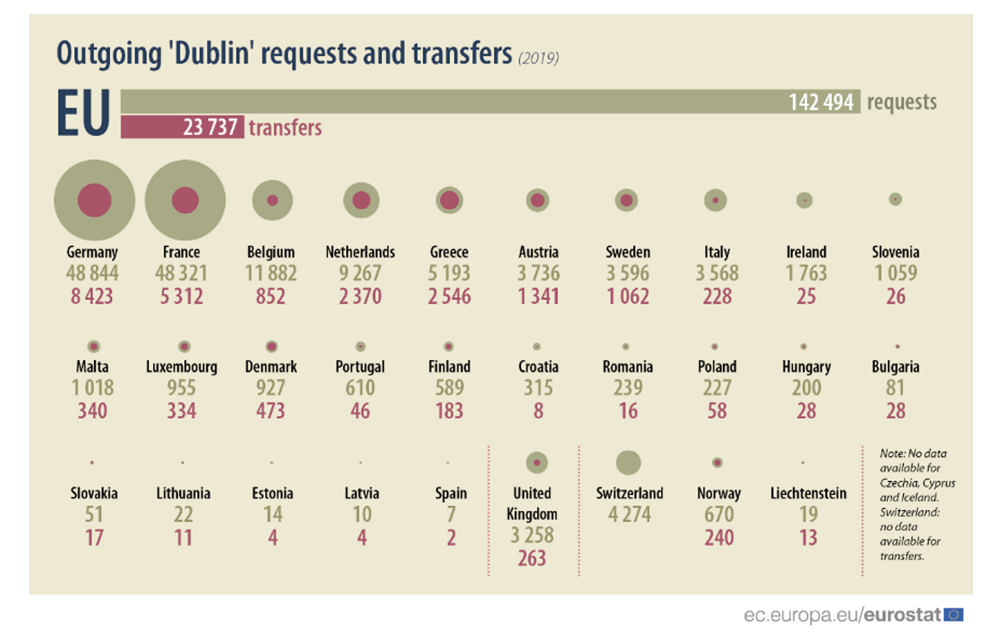

Another illustration of how the use of Dublin III transfers by the Irish state compares to the rest of the EU is that in 2019 Ireland issued just 1,763 of a total of 142,494 requests for transfer to another EU state. That was just 1.23% of the total. There were 23,737 successful transfers, of which the Irish state accounted for 25 – 0.1%.

The difference between the 817 transfer decisions recorded in 2019 by the Department of Justice and the EU figure of 1,763 is that presumably the first only records the number of requests that were even acknowledged by the state to whom the request for an outgoing transfer was made.

The rate of transfer in the EU was 17% of the total requests, compared to 8% here. Gript shall continue to provide the facts regarding all of this, regardless of who dislikes it.