The fines levied on the State by the EU for failing to meet targets in reductions of carbon emissions by 2030 could soar to €20 Billion, according to the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council – who also warned that continuous overruns in government spending is unsustainable.

The estimate of €20 Billion from the watchdog is more than twice the previous estimate of €8.2 billion made by the Climate Change Advisory Council in August of this year when the Council’s Chair, Marie Donnelly said that while €8.2 billion the baseline estimate but that the “higher end is really a question of how long is a piece of string”.

The penalty – described as “compliance costs” and levied if Ireland does not meet binding emissions reduction and renewable energy targets under both the EU’s Effort Sharing Regulation for emissions, and the Renewable Energy Directive under the Fit for 55 package – can be in the form of carbon credits, statistical transfers, or fines.

In theory, the carbon credits could be bought from other member states who have exceeded their targets – and the 2030 price of these traded credits by 2030 is currently unknown.

“Ireland is legally bound to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 and to stay within three sequential carbon budgets between 2021 and 2035. These require greenhouse gas emissions to be reduced by 51% by 2030 compared to 2018 levels, the IFAC said.

“However, projections for Ireland based on existing plans show it missing its requirements. These indicate a reduction of just 29% by 2030. Failing to meet these targets would incur some compliance costs. Estimates by Walker et al. (2023) put the costs at an annual average of about €0.35 billion up to 2030, when costs rise to €0.7 billion (0.2% of GNI*),” the watchdog warned.

The IFAC said that the previous lower estimates were based on assumptions that Ireland would follow through on measures to cut emissions that “it looks increasingly unlikely to implement” – and that the State would therefore face much higher compliance costs “potentially as high as €20 billion”.

That would mean the State would be on the hook for fines amounting to more than a sixth of the total tax take for the country in 2023.

The fiscal watchdog added that, on the revenue side, the intake of tax would be reduced by €2.5 billion per annum by 2030 – rising to €4.4 billion per annum in the long run because of “a sharp decrease in tax on fuel and energy use, which stems from lower excise duties and reduced petrol and diesel consumption; the lower VAT rates on electricity, and a decrease in vehicle registration tax and motor tax, which are both tied to emissions under current policies.

The government would also need to provide substantial supports to meet Ireland’s climate targets, the watchdog added, saying that those additional costs would likely come in at between €1.6 to €3.0 billion per annum over the years 2026 to 2030.

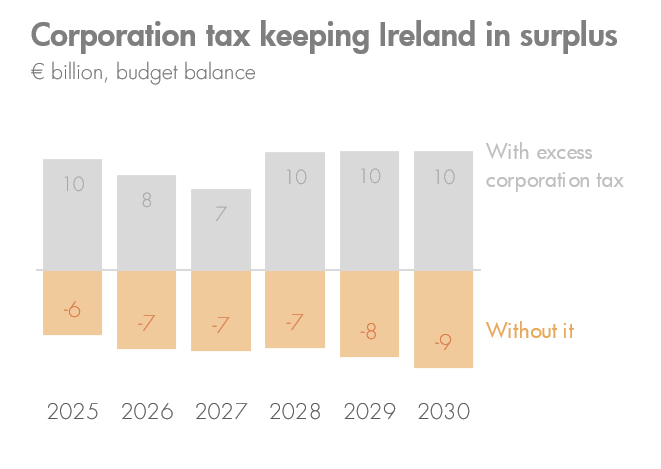

The Council also repeated warnings of an over-reliance on corporation tax receipts, saying that “phenomenal levels of excess corporation tax receipts, nearly €16 billion every year, are keeping Ireland in surplus.”

“Injecting these receipts into a strong economy is risky,” the watchdog warned. “These receipts may well increase, but they remain high risk.” Just three companies account for some 40% of the corporation tax receipts, they added.

The state would be running deficits of between €6 billion and €9 billion each year between 2025 and 2030 without the CT windfall, they showed.

“Awash with resources, spending has increased rapidly,” the IFAC said. “If this pattern continued and windfalls dried up, it would set Ireland’s public debt on a steep upward path. Rising ageing pressures would make this difficult to reverse.”

“The biggest risk is that budgets continue in this vein and exceptional corporation taxes dry up,” they warned – adding that the Government had only added a third of the excess funds in the two long term savings funds for windfall tax receipts.

Continuous overruns in spending were also criticised – with an overrun of €3.8 billion expected for 2024 which would make current budget forecasts “not credible”, the watchdog said.

Calling for a “more strategic course” to be set, the IFAC said it was “time to plan seriously” – and called for the Government to set out a sustainable rule it will stick to, curbing pressures and avoiding needless job losses in the next recession.

Realistic plans for health, housing, and climate challenges were needed, they added, while proposing that “exceptional corporation tax receipts” be treated “more like Norway treats its oil — as a high-risk, finite resource.”