Those of us comfortable in the familiar regarding history are having to brace ourselves for future storms. New technologies are laying waste to thinking of old as ever improving digitization, translation and online search functions supercharge researchers’ ability to target and interpret data.

Advances like DNA technology have upended decades of thinking, and we can add a new revision to the catalogue – the origins of the Irish national flag.

A first-ever referenced work on the origins of Ireland’s Tricolour flag has revealed its emergence in 1830, 18 years earlier than previously understood. The research has also revealed new first flights of the flag and previously forgotten figures, not least a female patriot who was the first to fuse the colours and give them their symbolism.

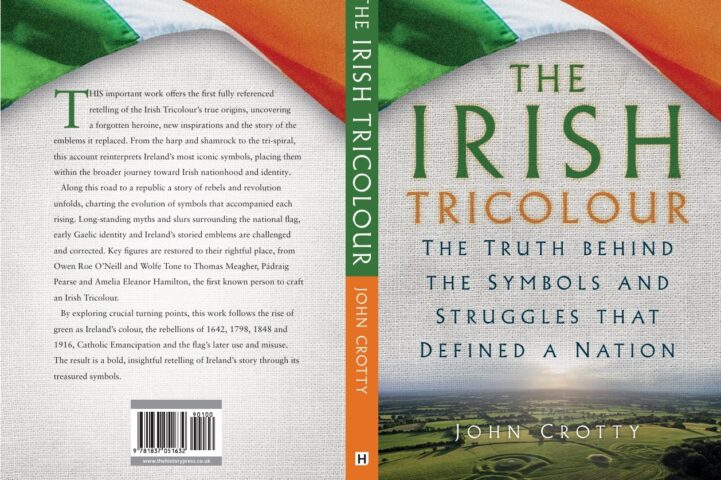

In the ‘The Irish Tricolour – the truth behind the symbols and struggles that defined a nation’, Ireland’s story is reinterpreted through its many symbols, beginning in 4000 BC with the Tri-spiral of Newgrange fame.

Also re-examined is the culture-rich era of Gaelic Ireland, which has provided much of Ireland’s retained symbolism today despite suffering from contrasting agendas. A period that was overly romanticized by 19th century historians underwent savage and overreaching revisionism in the 20th century, the pendulum still moving towards balance.

Gaelic Ireland was “a civilization of extraordinary value and values, one of the most sophisticated in Europe. Particularly in its later period following the fall of Rome, Ireland was a shining light of scholarly endeavor, complimented by legal advancement and community-based kinship”. Popular emblems that emerged during this period include the harp, sunburst and Gaelic knots.

The harp. in particular. has proven a symbol of remarkable authenticity, its extensive use in Gaelic Ireland stretching thousands of years. Its origin story was widely misunderstood in 20th century Ireland, at one point believed to be an English choice for Ireland in the 1500s. In reality, it was placed on azure by French heralds around 1260, centuries beforehand. The harp’s later adoption on green by the Confederate Catholics of Kilkenny from 1642 helped its ongoing use and state retention in 1922.

Most striking are new findings regarding the Irish Tricolour flag. Previously claimed to have been first flown on March 7, 1848, the research shows it had emerged and was popularized by 1830. It was inspired by the calls of influential Daniel O’Connell, who turned his thoughts from Catholic Emancipation to Repeal of the Union in 1829. Its aim was a Parliament in Dublin, one restored following its closure during the Act of Union in 1801. O’Connell sought to woo Ireland’s Protestants to the cause, frequently using language like ‘Let orange and green blend their colours henceforth… the general object to render their country that place of plenty and happiness which God and nature intended’.

There was no more influential voice in the country, making it no surprise the words saw action months later in Cork City, March 1830. A first ever physical union of green and orange was recorded in a cockade, or rosette, at a political event, its message of unity complimented by a speaker. The colours began to combine with frequency before a first ever Irish tricolour device emerged. It was likely partly inspired by the French Revolution of July 1830, the cockade crafted by forgotten female patriot, Emilia Eleanor Hamilton of Annadale Cottage, modern day Fairview, Dublin. Presented at a meeting to send salutations to the French, she created the symbolism we recognize in the tricolour today with two lines of an accompanying poem – “Let orange and green no longer be seen, bestained by the blood of our island”.

Her new symbol was picked up in the press of the day, even proposed for a national flag by London’s Atlas newspaper. It got a national launch three months later, the followers of Daniela O’Connell adapting their green-orange device to include white at an event to welcome O’Connell from taking his seat in London’s Parliament. Tricolours flew with abandon, the symbol adopted by the Repeal campaign in flag, banner and rosette format. Sometimes the simpler green-orange device was used, implying the same message of unity. The colours even became the choice of the anti-tithe (church taxes) movement and the tee-total campaigns of Father Matthew, being known to all.

First recorded flights occurred in America in 1831 and over a building in 1832, when a meeting protesting tithes (church taxes) saw the hoisting of an Irish tricolour over Dunsoghly Towerhouse, a 15th century structure in Saint Margaret’s, Dublin.

The symbolism saw declining use as O’Connell’s Repeal campaign stuttered before it got an important re-adoption in 1848. The Young Irelanders inherited the torch of increased Irish independence following the death of O’Connell in 1847, adopting his green-orange device for their membership cards in 1848. On March 7th a patriot flew an Irish tricolour in Enniscorthy, Wexford, in a much-publicized event to salute the French Revolution. The Young Irelanders adapted their existing green-orange device to incorporate white, flying the symbol in Limerick and Manchester.

An April trip to France saw the group return with a version of the Irish tricolour which they presented to a meeting in Dublin. The well publicized event and its phrasing in newspapers led later commentators to confuse the occasion as a first and novel event. In reality, it was the return of a well-known symbol and a first formal adoption by the Irish Confederates.

Other misconceptions tumble under analysis. The Irish tricolour did not first fly in Waterford City on March 7th, the event confused with a French flag flight. The tricolour was not donated by French women, this suggestion a slander against Irish efforts. A former policeman visiting Dublin in 1852 was shown an Irish tricolour captured by Dublin Castle in 1848, being advised it was presented to the Young Irelanders by ‘Paris ladies of easy political virtue’. This near two-century-old slur became wrapped up in the flag’s origin stories

In uncovering the truth of the Tricolour and Irish symbols and identity, a new story emerges. Ireland’s Gaelic age benefits from dispassionate assessment, being restored to a place of pride. The tricolour is shown to be an internal creation without French assistance, something hardly surprising for an island of unparalleled craft. We can trace the influence of Wolfe Tone and the ambitions of influential Daniel O’Connell. It was a device that began in green-orange form before Emilia Hamilton made history, assigning the three colours their modern significance.

Her symbolism was to the liking of the rebels of 1848, who gave the flag a revolutionary edge, fit for purpose in 1916. Its destiny was secured through their action. This nationally important book reveals the untold story of the Irish tricolour: its true origins, a forgotten heroine, and the emblems it replaced.

For the first time, a fully referenced history corrects long-standing myths and slurs surrounding Ireland’s national flag. It also reinterprets iconic Irish symbols — from the harp and shamrock to the tri-spiral — placing them within the broader journey toward Irish nationhood and national identity.

Along Ireland’s road to a republic, key figures are restored to their rightful place — from Owen Roe O’Neill and Wolfe Tone to Thomas Meagher and Pádraig Pearse. In addition is the revelation of the woman behind the flag, Emilia Eleanor Hamilton.

AUTHOR:

JOHN CROTTY is an Irish author and historian. His debut book, Spike Island, was critically acclaimed, featuring in Books.ie’s ‘Books of the Year’. He previously led the running of Spike Island as CEO. He has written for RTÉ and The Sunday Times and is an accomplished public speaker, appearing on several TV shows like the Discovery Channel, ITV’s How the Victorians Built Britain and RTÉ, in addition to innumerable radio appearances. He holds a degree from Swansea University and regularly speaks at history and writing events as well as contributing to historical podcasts. He has built an engaged social media audience interested in an accurate retelling of Irish history, and comprehensive historiography related to Irish symbols and identity, the Irish tricolour, Ireland in the Second World War and Spike Island.