We have been so often told that Ireland’s healthcare services would “collapse” without the continuation of mass immigration that the claim is now argued as an indubitable fact, which brooks no challenge and therefore requires no debate.

On occasion, as happened yesterday, a major media outlet will note that the number of Irish doctors and nurses and midwives and physiotherapists are continuing to leave the country in their droves, with nearly 7,000 Irish medical professionals now registered to work in Australia, up 86pc in six years.

But the obvious connection is never made, or at least it’s never said aloud: why are successive government driving out Irish healthcare workers while spending millions on recruitment campaigns to bring foreign workers here?

I wrote about this 18 months ago, when I said that digging deeper into the claims made by both Government and Oppositon – and the national broadcaster and every other establishment figure in between – in relation to healthcare should be taken as no disrespect to the many fine nurses, doctors and other healthcare practitioners that have come to work here to help provide essential services.

Sensible policies, and truthful arguments, should be able to withstand scrutiny. The suppression of such scrutiny is, in fact, the first strong indicator that said policy or argument is fatally flawed. It serves as a harbinger of what is to come.

As is also common in any discussion around our unprecedented immigration rates, and the unholy mess consecutive governments have made of this thorny issue, the facts have been evident to most of us for a long time, despite the hostile denials from the establishment and the name-calling from their enablers in the NGOs and the media. We can all see with our own eyes what’s happening in our communities, our parishes, our GAA clubs, and our families.

Young people are leaving because the right to a future in their own country is being destroyed by a inability to find a home; by HSE recruitment freezes for Irish staff while workers from abroad are brought; by the persistent cost of living crisis; and by ridiculous government waste – factors that are, of course, exacerbated by mass migration. Yet the government’s response is to issue more work permits and insist that more, not less, immigration is needed.

And so the Irish exodus continues: From Aisling Maloney’s comprehensive feature in the Sunday Independent yesterday:

Nearly 7,000 Irish medical professionals are now registered to work in Australia, sparking concerns about the impact on the Irish health service as the number seeking a better working life down under has risen by 86pc in six years.

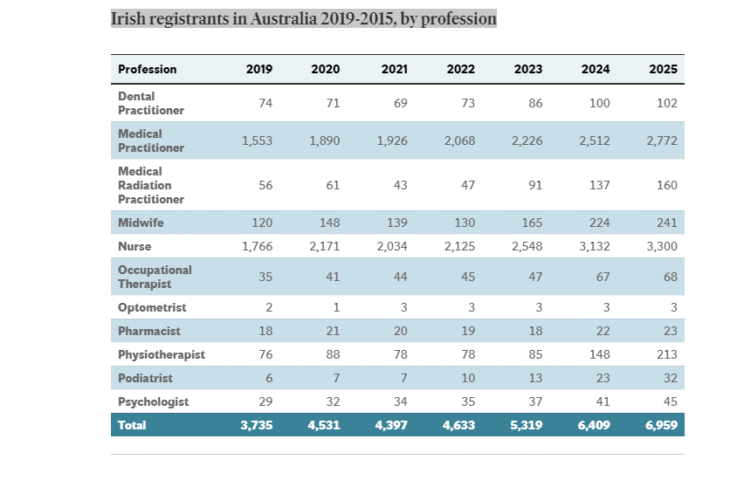

New figures from the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) show that 6,959 Irish medical professionals were registered in Australia last year, including dentists, midwives, pharmacists and psychologists.

This has jumped from 3,735 Irish healthcare workers registered there in 2019.

An Australian Health Agency chart included in the report gives an insight into the Irish talent that we are losing year after year to that country alone – with some specialities leaving in such numbers as to make the description of what’s happening as Ireland “bleeding expertise” seem entire appropriate.

It’s really important to remember when looking at the chart that the HSE has been told for at least 15 years that the recruitment freezes imposed for Irish staff, and the suboptimal working conditions being offered, are driving our talented medical experts abroad.

Look at the numbers: while the numbers of Medical Practitioners leaving has spiralled, and the number of midwives gone to Australia has doubled, the number of physios has tripled. The number of Irish medical professionals registered in Australia rose by 86% in just six years.

“Individual Australian states have strategies for recruiting sought-after Irish healthcare staff, with lucrative relocation bonuses,” the Independent explains, adding that “the South Australian government is offering $15,000 (€8,800) to support healthcare workers moving from Ireland”.

Now, the Irish government are also spending large amounts of money on recruitment for healthcare workers, but only on those who are foreign nationals. Is this not a very strange situation?

For example, after the HSE announced a recruitment freeze on nurses, midwives and junior doctors in October 2023, it continued to hire health staff from abroad right into 2024.

The Irish Medical Organisation (IMO) warned that the recruitment freeze lead to doctors “emigrating in increasing numbers”, while back as far as 2010, the Irish Nurses and Midwives Organisation (INMO) was rightly complaining that the UK’s National Health Service was recruiting “whole classes of graduating nurses” from Ireland because the state was then also implementing a recruitment embargo.

Most of the 1,600 nurses and midwives graduating in 2010 from Irish universities would emigrate, the INMO estimated, even though some 12,000 nurses from the Philippines, India and elsewhere had been recruited by the health service since 2001 to work in Ireland – at an estimated cost of recruitment of more than €7,500 a head.

One Irish nurse who was interviewed said that only 10% of those who had trained and qualified with her stayed in Ireland – adding despite having “what society considers ‘good jobs’” – it was almost impossible “to save for a mortgage or have any quality of life in Ireland”.

Research by Dr Niamh Humphries for the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland found that only one in three doctors she interviewed planned to return to Ireland. It’s not just that they aren’t being encouraged to, either. The roles are actively being filled by a healthcare system which seems focused on recruiting healthcare workers from abroad as a favoured strategy or even a default position, rather than a genuine response to shortage which would also surely involve an a

In 2019, 250 Irish nurses living and working in Australia famously gathered outside the Sydney Opera House with a massive banner with a message to the Irish government: “Give us a reason to come home”. They weren’t given one.

Why aren’t the HSE visiting Australia and asking Irish nurses to come home, and insisting the state provide the kind of working conditions that would make that possible? Why did they choose instead to spend some €7,500 a head on recruitment costs to bring 12,000 nurses here from abroad – that’s a total cost of €90 million euros, by the way, and those costs have only increased since.

Are there unspoken preferences at play in relation to recruitment? When announcing the HSE recruitment freeze in October 2023, for example, an exception was made so that “up to 1,400 posts across nursing, midwifery and health and social care will therefore continue to be filled into 2024 from overseas candidates, despite the recruitment freeze in place domestically.”

A healthcare professional told The Journal that she was “horrified” and “in shock” to find out that she and others had been “bypassed” by international candidates for positions during that recruitment freeze, even though she and her colleagues were on panels – in line – for the roles.

Noting that the recruitment embargo was “all about cost-saving”, she questioned the logic of hiring people abroad as it is typically much more expensive than hiring staff within Ireland.

As I noted previously: she’s absolutely right to question the logic. Maybe it’s not that the HSE can’t get Irish staff, maybe it’s that they don’t want them. Why might that be?

Is it the case that the HSE might prefer to hire staff from abroad precisely because they don’t make the same demands or have the same expectations, especially if they see working here as a temporary measure, and therefore aren’t fazed by the difficulties Irish workers face regarding mortgages and home ownership and setting up families.

There might be a clue in as to the mindset in the HSE in a discussion around the difficulties faced by one recruiter who noted that “while the HSE is losing Irish staff to Australia and elsewhere, it is also actively recruiting in places where we can compete better on wages and working conditions, such as India and the Philippines.”

Does that mean the HSE is recruiting in poorer countries amongst people who are willing, perhaps, to put up with the chaos that’s leading to longer hours and a pressurised work environment. That comes close to a kind of exploitation, in my opinion.

No-one is interested in discussing the brain-drain for poorer countries and the disruption to the development of their health services by the endless mining of their skilled people for the benefit of richer countries? Then there’s the added disruption and fracturing of family life by the needs of globalism and its insistence on an endlessly transient workforce.

In relation to our collapsed birth rate, there’s the very pressing concern that the Irish healthcare workers leaving in such large numbers are mostly of an age where they might be expected to marry and have families within five or ten years.

That has been made impossible in Ireland by the housing and cost of living crisis which are compounded by immigration – obviously not just of healthcare workers. Huge tech companies like Google are bringing in up 80% of their workforce with obvious impacts on rental and home auctions. At the other end of the scale, the asylum system has also demanded homes for in excess of 200,000 people in recent times, while the pretence continues that all this inward migration-driven demand has no effect on the cost of houses.

There’s yet another largely unspoken consideration: our healthcare services have also become overburdened in part because we have allowed an enormous influx of people into the country who not only need housing and schooling but medical care. It is simply absurd to point to the huge percentage of migrant healthcare staff without also recognising that if 25% of our population is now foreign born, then a quarter of those requiring medical care and on waiting lists etc are likely also people who came to live here.

In addition, investigations like that carried out by Gript which showed that 82% of doctors that were sanctioned by the Irish Medical Council were foreign trained.

It comes down to this: no functioning society should be relying so heavily on foreign healthcare workers because so many of our own are being driven abroad – by factors often exacerbated by immigration.

The 7,000 Irish healthcare workers in Australia alone are a compelling reason for us to demand the government pauses to take stock. This is mess of their making – and this destructive vicious circle needs to come to an immediate end.