A meeting was held this evening at Leinster House in opposition to the EU’s insistence that it will compel Ireland to introduce deeply unpopular Hate Speech laws.

The event, hosted by Senator Sharon Keogan and Free Speech Ireland, featured contributions from MEP Michael McNamara. Deputy Ken O’Flynn, Laoise de Brún BL and Dominic Wilkinson BL spoke at the meeting

Dominic Wilkinson BL questioned whether “more regulation” was an appropriate response to “hate and hatred” when “good manners” is what usually defines what passes for acceptable and unacceptable speech.

He said that the European Council was unhappy with Ireland’s removal of the ‘hate speech’ element from the 2022 draft of the ‘hate speech bill’ because it did not satisfy the provisions of a 2008 document which seeks to ban the dissemination of “tracts” on issues such as religion, race, or decent which could “influence other people’s opinions” on such topics.

He said that Ireland has an “opt in” with regard to European Directives and that the recent fierce opposition to the 2022 draft of the hate speech bill could be taken as an “opt out” regarding laws that criminalise speech. Wilkinson added that the EU can “write” to Ireland asking that it agree to bring forth such laws, but that ultimately the “rule of law” regarding how different member states respond to directives “must be respected”.

Speaking from Brussels, MEP Michael McNamara said that Ireland is “essentially exempted from most legislation related to crime” under the Lisbon and Nice treaties, which he said is why the Dáil had to vote into the EU Migration Pact.

He said that on the 11th of March Ireland had agreed to “opt in” to measures regarding hate speech, saying, “Everyone thought it was a great idea during covid when most people’s critical faculties were suspended.”

McNamara said that it was “legitimate” of the EU to expect Ireland to implement measures it has signed up to, but that “people have right to know what’s expected of them” when it comes to criminalising various forms of speech and that the practicality of these laws means “people not being offended” and that “the act of offending someone seems to become a criminal offence.”

Response of the Department of Justice.

In a statement to Gript, the Department of Justice said the “Transposition of Council Framework Decision 2008/913/JHA of 28 November 2008 on combating certain forms and expressions of racism and xenophobia was formally notified to the European Commission before the deadline in November 2010.”

“In 2014, the Commission published a report on the implementation of the Framework Decision, which outlined concerns over correct transposition in over a dozen EU member states, including Ireland., it said.

It sais that a Letter of Formal Notice “was received from the Commission in October 2024, setting out its view that Ireland has not fully transposed the Framework Decision, specifically certain elements of Articles 1, 4, 8 and 9 relating, among other things, to criminalising public incitement to violence against a group or a member of such group based on certain characteristics, as well as condoning or denying international humanitarian law crimes such as genocide or crimes against humanity. A formal response was issued to the Commission.”

In reference to the The Criminal Justice (Incitement to Violence or Hatred and Hate Offences) Bill 2022, the department said this “was developed with the twin aims of updating the law on incitement to hatred and introducing the outstanding provisions of the Framework Decision to bring our law in this area into line with our European neighbours.”

The department says, “it subsequently became necessary to amend the Bill in the Oireachtas by removing the incitement to hatred provisions from the Bill in order to progress the hate crime elements. The resulting Criminal Justice (Hate Offences) Act 2024 fulfilled the State’s obligation with regard to certain elements of the Framework Decision, in particular Article 4 which required measures to ensure that racist and xenophobic motivation is considered an aggravating circumstance and can be taken into account by the Courts in sentencing for an offence.”

“The Commission recently issued a Reasoned Opinion to Ireland in respect of the outstanding articles. The Department is now examining this document and is actively engaging with the Commission to address the issues, and provide a response no later than 7 July.” the statement concluded.

Laoise De Brún BL, and founder of The Countess said that “the clock is now running down” on freedom of speech in Ireland, comparing the implementation of hate speech laws to that of gender self-identification laws saying that Ireland “dragged our feet for ten whole years” before going “overboard”, something that she attributed to the “stranglehold” of NGOs both at home and in the EU more broadly.

She called these issues the “sacred cow of progressivism” calling for a debate on how the permitting of biological males who say they are female to use women only spaces, such as bathrooms and changing facilities, cannot be had “only one side is protected”.

De Brún said that many trans activists “view simple truthful expression of biological reality as meeting the threshold of hate” and that any conversation around this “could be completely censored” as the “official narrative” states that “trans-women are women.”

She said that this leads to a situation where activist groups “get to define what hate is”, expressing dismay that, just as the UK Supreme Court delivered a “crystal clear” ruling on how the rights of trans identified males impinge on the rights of women, at home there seems to be a renewed emphasis on building a “broader architecture of censorship”.

Pointing to “a whole lot more to worry about as well,” she said that the Digital Services Act (DSA) would be “administered from Dublin” to implement “German style hate speech laws from Europe”, calling for the Irish capital to be made “a hub for freedom of speech, not censorship.”

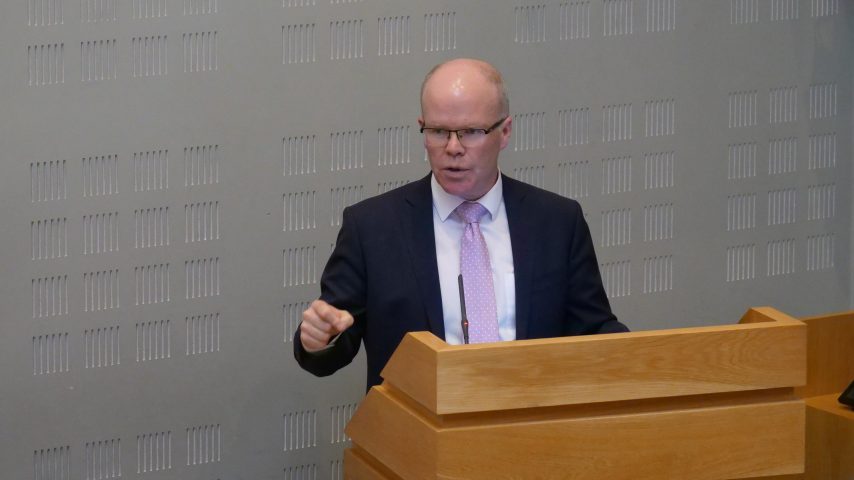

Aontú leader Peadar Tóibín spoke of how a “competition of ideas is the engine of democracy” and how “the best ideas percolate to the top and become public policy.”

He said that while Aontú “hates hate speech” expressing a wish that those who engage in discourse do so “with respect and dignity”.

Tóibín said that Ireland faces “cultural threats” to freedom of speech, namely our “small media”, which he says compromises around 1,000 “national journalists”.

He said that there is “very little competition in terms of ideas” and that the “media is the oxygen on which politics lives”, and that while Ireland “dresses up in the colours of diversity” it “opposes actual diversity” of opinion.

“All the views in the world are welcome as long as they agree with ours,” he quipped.

Independent Ireland TD, Ken O’Flynn said that this point in time was “a pivotal moment” and that while the hate speech legislation is “clothed in language of protection” but is “close to the language of censorship.”

He said that people have the right to speak, to offend, to provoke, and to persuade, and that this freedom was the “instrument of a society that remains free” and that the taking of offence by any individual was “wholly subjective”.

He harkened back to the burning of the Library of Alexandria saying that this act of the suppression of information showed how “fear of thought burns what it cannot control”.

“When speech is strangled, the truth cannot breathe,” he said.

O’Flynn said that Ireland must “resist” its “infantilisation” and that the “Irish people need to be protected from people telling them what to think,”.