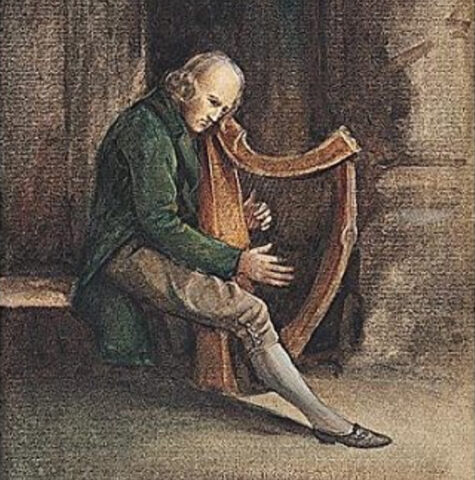

On this day in 1809, the Dublin Harp Society (July 1809 – December 1812) was founded. The society helped lead the revival of Ireland’s ancient musical instrument depicted in the national emblem – around the time of its demise in the early 19th century. It was inaugurated with an influential list of subscribers, including Scottish historical novelist, poet and playwright, Sir Walter Scott, and Irish writer, lyricist and poet Thomas Moore.

Though harp symbols that can be seen at Dublin Castle date back 200 years, the history of Irish harps goes back over a thousand years.

The year prior to the formation of the Dublin Harp Society, the Irish Harp Society, which was formally associated with Belfast, was founded on St. Patrick’s Day in 1808. The Irish Harp Society was founded with the primary aim of giving blind boys and girls the means of making a living by teaching them the harp, and its secondary objective was the promotion of the study of the Irish language, history and classical times.

In July the following year, the ‘eccentric but well meaning’ John Bernard Trotter started the Dublin Harp Society. Trotter, born in Downpatrick in 1775, graduated from Trinity College Dublin in 1795. After considering a vocation in the Church, starting by taking Deacon’s Orders, the 34-year-old left to study for the bar, but his career was plagued by his poor health which continued for the rest of his short life.

Trotter was passionate about the traditional music of Ireland, and was the leading force in the Dublin Harp Society, even using the house where he was living in the north Dublin suburb of Richmond for its headquarters.

Through its formation, he sought to expand the Belfast Harp Society into a Society which would embrace all of Ireland. The idea ignited a huge amount of public interest, with many seeing the subject matter as something novel and romantic.

Trotter injected the society with a huge financial boost, giving £200 of his own money yearly to help it grow. He entertained ‘in great style’ at his home-turned-headquarters, and guests were delighted with the strains of the harp. Patrick Quinn, one of the youngest blind harpers who played at the Belfast Harp Festival in 1792 was among those who would entertain guests with his talent. He had joined the society through Trotter, and also played at the grand O’Carolan commemorations organised by Trotter in 1809, which predominantly featured distinguished contemporary musicians including the likes of Sir John Stevenson (who had arranged Thomas Moore melodies).

Quinn was so thrilled at having been selected to play at that event that having returned home to his native county Armagh, he refused to play the fiddle as he had previously routinely done at public gatherings including wakes and ‘merry makings’, and which had been his central source of income.

While the rules and regulations of the Dublin Harp Society were published in 1810, the movement ended up declining at the end of that year, and became defunct in 1812 owing to Trotter’s extravagant hospitality eventually leaving him bankrupt. He died in Cork in 1818, aged 43 after battling ill health.

Following Trotter’s death, the Irish Harp Society at Belfast was re-instituted. A meeting was held to distribute a fund of £1,200 which had been forwarded by benevolent supporters in India in order to “revive the Harp and Ancient Music of Ireland”.

The meeting took place on 16 April 1819, and classes resumed at the Society. Thomas Verner was chairman of the Society, and Edmund B’Bride taught. He was succeeded by Valentine Rennie (1819-1822).

According to Petrie,

The effort of the people of the North to perpetuate the existence of the harp in Ireland by trying to give a harper’s skill to a number of poor blind boys was at once a benevolent and a patriotic one; but it was a delusion. The harp at the time was virtually dead, and such effort could give it for a while only a sort of galvanised vitality. The selection of blind boys, without any greater regard for their musical capacities than the possession of the organ of hearing, for a calling which doomed them to a wandering life . . . was not a well-considered benevolence, and should never have had any fair hope of success.”

From 1803-1823, the harp became stylish, being taken up as a “fad” by many titled dames, making it popular but only temporarily. After Rennie died in 1837, the Society once again went into decline, however, a new teacher, James Jackson, was appointed in January 1838 for one year. Things came to a close in 1839 after two decades.

Three years later, in January 1842, a revival came when a new Harp Society was inaugurated in Drogheda, owing to the passion for the instrument held by Fr. Thomas V. Burke, O.P of Drogheda. He had a class of 15 pupils, and that year, the Society obtained 12 new harps made in the town at a cost of £3 each.

Fr Burke was a famous harpist and composer, and was family minstrel to the Shirleys. The society collapsed in 1845, and the famine followed. The harp was largely neglected until the Irish Ireland movement, launched by the Gaelic League once again brought the national instrument back to life.

Harp competitions which have taken place at the Feis Ceoil and the Oireachtas since 1897 are evidence that Ireland’s national instrument lives on to this day, aided by the zeal and relentless effort of individuals such as John Bernard Trotter and Fr. Thomas V. Burke.