LOOKBACK: This article was first published on 10 August 2022

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

The story behind the republication of this book is in some ways as interesting as its content. As explained in the prologue, in 2007 Damien Richardson found a hard back copy of Fr. Dennis Murphy’s book, which was originally published in 1896, while cleaning out a house in Dublin.

Damien was almost ten years into recovery from heroin addiction by that stage. Like other young people from the north inner city in Dublin, Damien had succumbed to the temptation of a drug that has wreaked havoc among families and communities for over 40 years since its introduction by criminal gangs whose successors still operate throughout Ireland, and whose violence and corruption continues to impact on the society as a whole.

Damien’s path to redemption was opened to him by his father who persuaded him to visit Medjugorje in August 1996. A time I remember well myself as it was the month my daughter was born and in which people from where Damien was from on the north docks and in East Wall where I was living at the time and other parts of Dublin were engaged in confronting the drug dealers who were threatening to overwhelm the city.

Damien’s personal journey began with him taking heroin before boarding the plane in Dublin and then experiencing what he described as a “mini conversion” while in Croatia. One that led him to the Cenacolo community and eventual freedom from his addiction. He spoke in Croke Park during the Festival of Families presided over by Pope Francis in August 2018, and was mentioned by the Pope in his address.

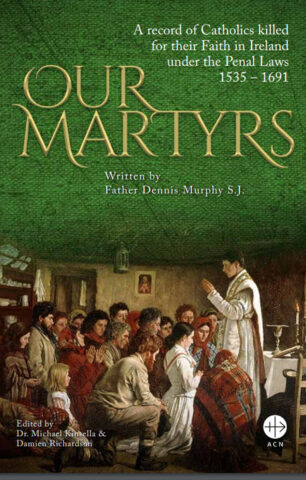

All of this led to the republication of Fr. Murphy’s book, Our Martyrs, which is now in its fourth edition since Damien initiated its republication in 2010 under the auspices of Aid to the Church in Need which was founded in 1947 to provide support for Catholics in the countries taken over by the Stalinists after the ending of World War II.

All proceeds from the book, which can be purchased at go to assisting ACN in providing aid for persecuted Catholics around the world, and in particular in African countries where large numbers of people continue to be murdered, as happened recently in Nigeria, for no other reason than their faith.

Which is fitting, given that the book details individual accounts of hundreds of Irish Catholics put to death between 1535 and 1691. Some of the names such as Oliver Plunkett will be familiar, but most have faded into historical obscurity, along with the many thousands of others whose names are not recorded but who died over the centuries of persecution of Irish people for no other reason than their being Irish, Gaelic and Catholic; the latter also including many Catholics who were descendants of earlier settlers who had become Hiberniores Hibernis ipsis – Níos Gaelaí ná na Gaeil féin.

The accounts of the tortures and manner of death endured are often horrific and lend substance to the dry bones of the history of the long period of terror visited upon our people. Among the victims were Archbishop Diarmaid Ó hUrthuile of Cashel who in March 1584 was tortured by having his feet boiled in oil and tallow. He was later hanged at a site where Fitzwilliam Street now crosses Baggot Street.

The link between the assault on the Gaelic order and on the religion of the people was underlined by the deaths in 1651 of two priests, Father Bernard and Laurence of the Ó Fearghail family of Angaile in county Longford, as well as the Ó Fearghail Chief Louis who was captured by the Cromwellians at Athlone the same year.

In 1647 the Ó Briain traitor Morrough, Lord Inchiquin, Morrough na dtoitean, carried out an horrific massacre at Cashel where 912 people were murdered inside the Cathedral and several thousand of the citizens put to death within the town as a whole.

It is generally unhealthy to dwell upon the misdeeds of the past, but it is worse again to consign them to the category of their never having taken place at all. Especially given that those who deny that history share with their predecessors in the English armies and their Irish collaborators a common mission of destruction.