“Ireland was a dull and grey backwater until the 1990s when progressive secular liberalism, in both its social and economic facets, catapulted Ireland into high development levels.” This is a conventional narrative in present-day Ireland. For example, the Irish Times’ liberal sage, Fintan O’Toole, has written that “the real Irish revolution is the one that has taken place since the early 1990s.”

But is this true? Did Ireland only start developing high living standards in the 1990s? Or does more careful analysis show that Ireland fared quite adequately in the face of adversity going back decades, and, if so, what could explain this pre-1990s development? In this author’s opinion, the Catholic Church played a positive role.

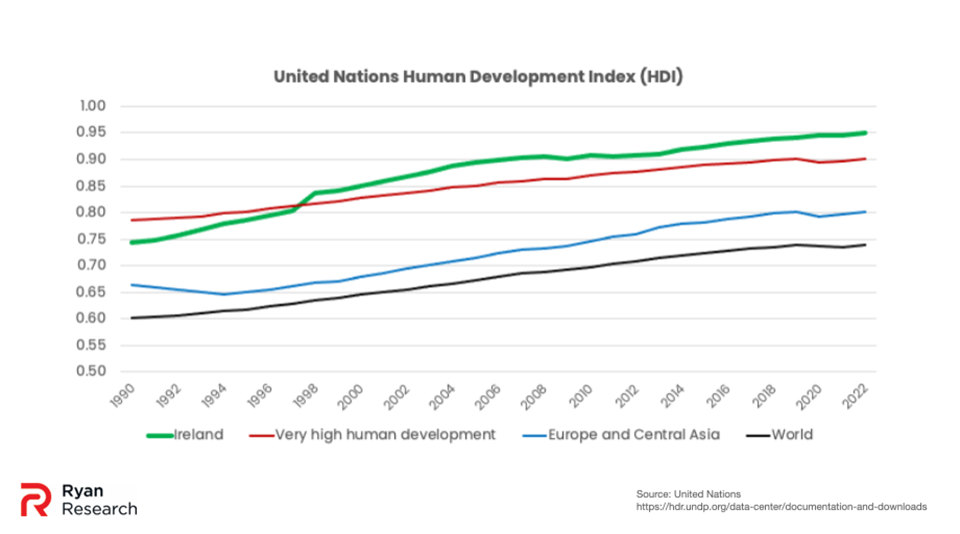

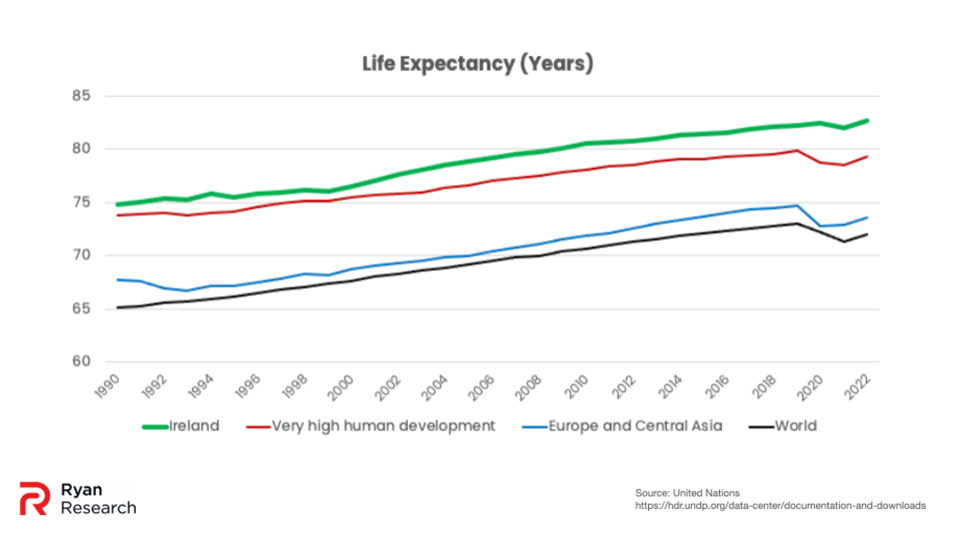

Former Irish Ambassador to the US Daniel Mulhall used the United Nations’ Human Development Index (HDI) to demonstrate Ireland’s current high ranking at 7th place. Mark Henry highlighted life expectancy, a key input to the UN’s HDI, had increased so much since 1990 it “transformed” Irish living standards. The UN HDI and its component inputs are worthwhile measurement tools.

Measuring Irish Development

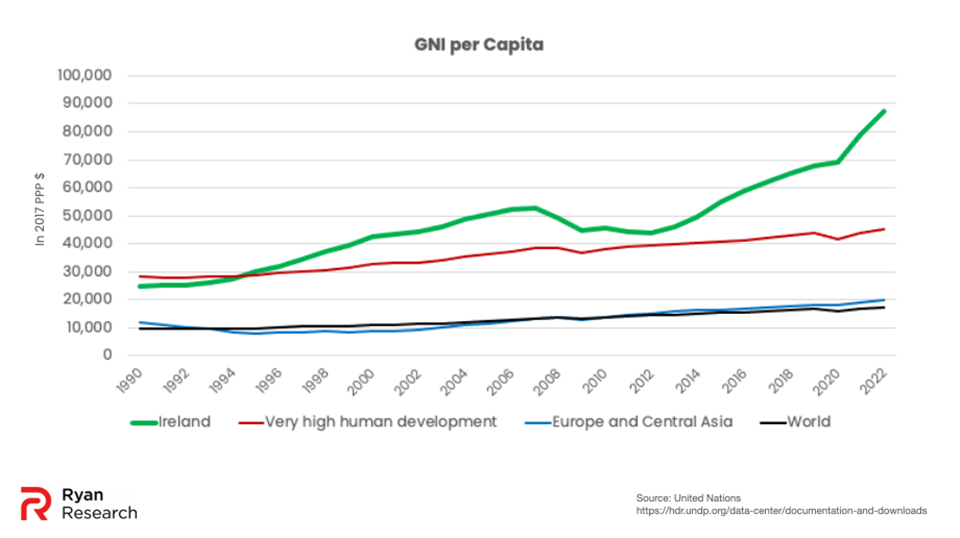

The UN’s HDI is broken down into three categories: life expectancy, years of schooling, and Gross National Product (GNI) per capita. The UN’s historical HDI data revealed that Ireland looked much better than the contemporary inverse-nostalgia would have you believe. In 1990, Ireland was just shy of meeting the average index value of countries classified to be very high in human development. Ireland’s HDI value was 12 percent higher than the average of Europe and Central Asia and 24 percent higher than the average of the world.

Figure 1

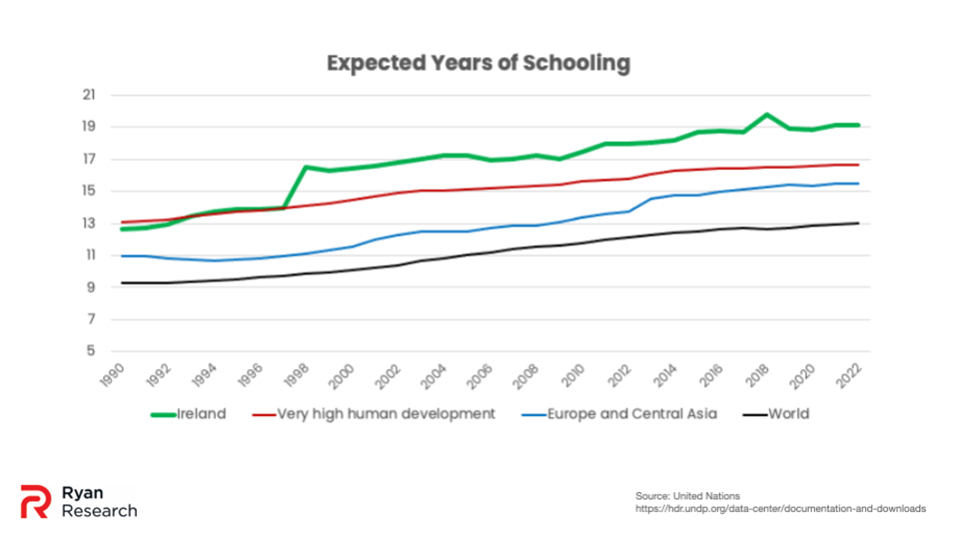

However, the individual components of the HDI revealed an even better Irish performance. In 1990, Ireland’s expected years of schooling, of 12.7 years, was just 3 percent lower than the average expected years of schooling for countries of very high human development, at 13.1 years. Irish educational attainment was practically the same as very high human development countries until Ireland surpassed them in 1998 with 17 percent more expected years of schooling.

Figure 2

Irish life expectancy was even better. In 1990, Irish life expectancy was 74.8 years compared to very high human development countries’ average of 73.9 years. Ireland was not just outpacing the global average by an astonishing 10 years, but also nearly a year above the most advanced countries. This review of life expectancy and expected years of schooling suggests that extreme pessimism about Ireland’s past is unwarranted. As far as these two metrics are concerned, Ireland already had close to or above very high standards, according to the UN’s rubric, at the starting point of Ireland’s secular liberal transition.

Figure 3

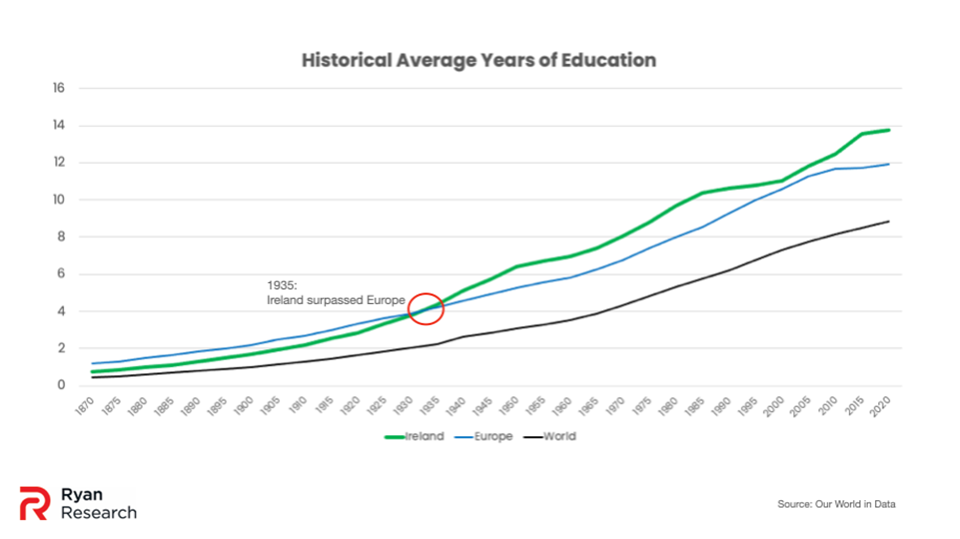

Further historical data reveals a similar trend. According to Our World in Data, the Irish average years of education was 38 percent below the European average and 59 percent above the global average in 1870. The Irish average years of education then surpassed the European average by about 1935. By 1950, the Irish average reached an all-time-high of 21 percent higher than the European average. In education, the Irish performed much better than their peers throughout most of the 20th century, which is much earlier than usually suggested.

Figure 4

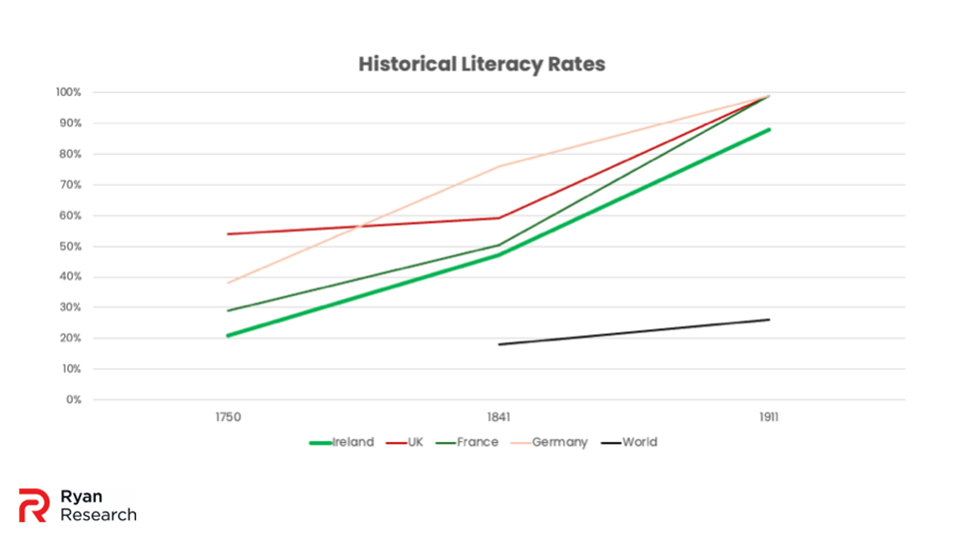

To find earlier data, a variety of sources were compiled to generate estimates of historical literacy rates across Ireland, the UK, France, Germany, and the world. While these estimates might contain a margin of error due to their older origination, their general trends are worth assessing to link up with the more accurate data sets that began after 1870.

In 1750, 21 percent of Ireland’s population was literate which was lower than in France, Germany, and the UK (mostly for reasons examined below). By 1841, the Irish literacy rate more than doubled to 47 percent and then, in 1911, it reached 88 percent. From 1750 to 1911, the Irish literacy rate increased by 319 percent, which was much greater than France’s 241 percent, Germany’s 161 percent, and the UK’s 83 percent. What this means is that the Irish educated their population at an amazingly fast pace to reach parity with their European peers who reached such levels of education over a much longer period.

Figure 5

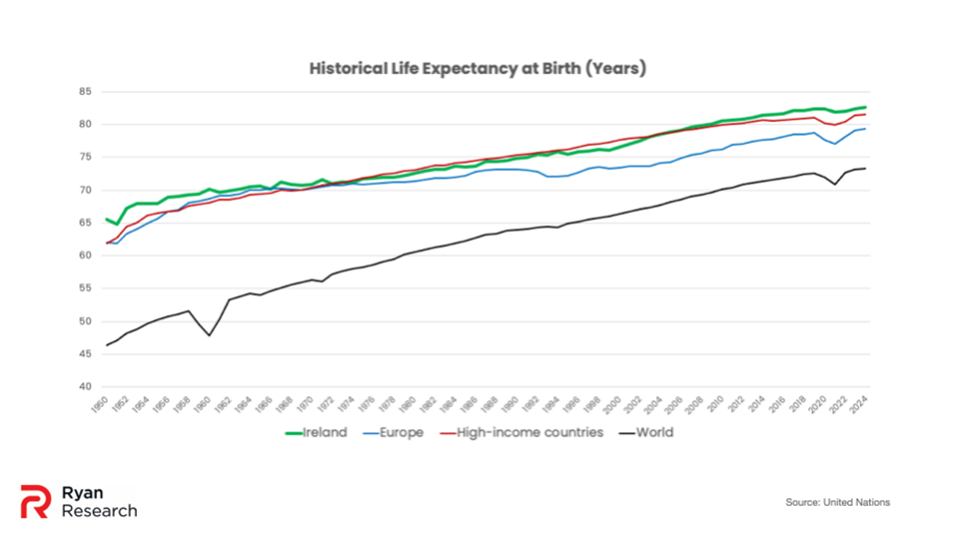

Next, Irish life expectancy showed a similar trend. In 1950, according to UN data, Ireland had a higher life expectancy than the averages of high-income countries and Europe – Irish life expectancy was 6.1 percent higher than that of high-income countries and 5.8 percent higher than that of Europe. Ireland maintained this incredibly high standard across the last 74 years, only falling 0.1 percent below the European average for one year in 1966.

Figure 6

For older data on Irish life expectancy, Brendan Walsh’s “Life Expectancy in Ireland since the 1870s” in The Economic and Social Review shined more light on the topic. According to Walsh, “Given the acknowledged poverty of the Irish population and backwardness of the economy well into the twentieth century, the relatively high life expectancy estimated from the 1870s onwards has evoked some surprise.” In 1871, Irish life expectancy was about 50 years while life expectancy was about 43 years in England and Wales.

Quoting other sources Walsh wrote, “at the turn of the twentieth century the expectation of life in Ireland was about the same as in the United States or England and Wales, and higher than in Germany…[there were] lower rates of infant mortality prevailing in Ireland relative to England and Wales in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.” Similar to the historical findings of educational attainment and literacy, historical Irish life expectancy fared very well relative to its peers.

It is therefore clear that Ireland performed remarkably well in the development categories of education and health well before the 1990s. This is even more impressive in the context of the adversity faced by Ireland because of the legacies of imperialism, impoverishment, and conflict. This brings us to the question of: who was most responsible for education and healthcare in Ireland? The Catholic Church held that role.

The Role of the Catholic Church

As a preface to this section, it must be noted that Gaelic Ireland was known as the land of saints and scholars for its cultural sophistication. Ireland produced great works of literature, law, and art. Many Irish scholars in that period went abroad to spread their knowledge where they advised monarchs and established Irish-style monasteries, the precursors to the modern European university systems. This cultural sophistication was only substantially degraded at the critical inflection point of the 17th century.

After the destructive conflicts of the Tudor Conquest, Cromwellian Invasion, and Williamite War, Ireland was finally under the total domination of England. Oppression was codified in things like the Penal Laws. For example, the Education Act of 1695 prohibited the education of Catholics. England legally prohibited industrialization in Ireland which prevented the Irish from attaining the productivity gains and subsequent developmental benefits from it. Thus, Ireland’s relative backwardness to its European peers was only about a 150 year blip in the entirety of Irish history – a blip caused by artificial legal prohibitions directly limiting Irish educational attainment and economic development.

Finally, it would be invalid to suggest that without the outside influence of a foreign Catholic Church, the Irish, left to their own devices, wouldn’t have achieved such improvements. The Irish converted to Catholicism in the 5th century and had since been enmeshed in the Catholic Church. As stated previously, many of the most influential clergy were Irish. While the Catholic Church is an international institution, we cannot lose sight of it being an institution with Irish people. Thus, Irish people through the Catholic Church shaped improvements in Ireland nominally attributed to the Catholic Church.

However, the Irish laity didn’t leave matters solely to their Irish religious leaders either. The Irish laity went out of their way, after tremendous tribulations, to rebuild what they lost in collaboration with the Catholic Church. Under the threat of persecution, Irish Catholics created the hedge school system. In secret, parents would pay a teacher to educate Irish Catholic children in a house, barn, cave, or other such place. According to P.J. Dowling, a Catholic priest “either appointed the teacher himself or approved of his appointment.”

The core subjects taught were reading, writing, and arithmetic, often in both English and Irish. Depending on the teacher, other subjects like history, geography, Latin, and Greek were also taught.

In 1835, an observer noted that a rural 12 year old boy trained at a hedge school was able to read the Bible in Greek. Of course, Catholicism was instilled as well. According to Tony Lyons, the Catholic Church “took it for granted that the schoolmasters…would teach the Catholic catechism; teachers who did not do so were summoned to appear before the bishop, reprimanded for their neglect and forced to promise to teach catechism in future.” At the end of the 18th century, it was estimated that there were 9,000 hedge schools attended by 400,000 students.

Some reforms were passed by this point which partially provided more freedoms to Catholics to pursue education. According to Tom Walsh, “Catholic teaching orders also established schools from the end of the eighteenth century, including the Presentation Sisters (1791), the Irish Christian Brothers (1802) and the Mercy Sisters (1828).” These Catholic teaching orders educated disadvantaged and impoverished Irish Catholic youth living under colonial rule at that time.

In particular, the Irish Christian Brothers’ founder Edmund Ignatius Rice gave up his successful business career to dedicate his life to educating the poor youth. He was so successful in this calling that Pope Pius VII made the Irish Christian Brothers an official pontifical congregation in 1820. Irish Christian Brother schools flourished in Ireland and eventually around the world where they educated numerous students, including this author.

In 1831, the national school system was established in Ireland. The system provided funds for the building of schools and salaries of teachers. It also authorized control to all religious bodies without exclusions and gave more leeway, in some respects, due to the successful negotiations of the Catholic Church. While the system was not intended to emphasize one faith over the other, due to the much larger Catholic population, it de facto allowed for the Catholic Church to dominate education in Ireland, especially outside Ulster.

This allowed Irish education to be formalized and centralized. The downsides of the decentralized hedge school system were that there were no agreed upon standards and the higher levels of the Catholic Church hierarchy had minimal insight into their operations. Thus, the Catholic Church advocated more direct control and administration of the schools to enhance the educational quality.

The Archbishop of Dublin Paul Cullen, who was the commanding figure of Irish Catholicism in the 19th century, made education a primary goal. For example, University College Dublin was founded as the Catholic University of Ireland in 1851 to provide Irish Catholics with third level education of non-Protestant orientation as part of Cullen’s overall goal. This seemed necessary after more and more Irish Catholics were becoming ever more educated and needed a third level outlet.

By 1900, the national school system included 8,684 schools with 770,622 students. In 1800, 8 percent of the Irish population was a student compared to in 1900 when 18 percent were students. These Catholic-run schools more than doubled the number of children in schools, relative to the population. After over 100 years of Irish independence since 1922, Catholic administration of education continued. At present, The Irish Times reports that almost 90 percent of primary schools and 50 percent of secondary schools are Catholic.

Turning to healthcare, the Catholic Church also had a substantial role. According to The Irish Times, “the running of the Irish health service was largely undertaken by religious orders in the past. Orders of nuns were responsible for the setting up of many of Ireland’s hospitals in the 19th and 20th centuries.”

For example, Catherine McAuley founded the Sisters of Mercy in 1831 in Dublin. They focused on education and healthcare. In the ensuing years, a number of cholera epidemics struck where the sisters took a large role in nursing. In 1861, they founded the Mater Misericordiae University Hospital in Dublin which still operates to this day and serves as a teaching college for University College Dublin. The Sisters of Mercy are also a large international institution that enshrined McAuley’s legacy in the proliferation of further healthcare facilities.

Even one of the most prominent American Presidents, Abraham Lincoln, remarked that the Sisters of Mercy showed a “benevolence seen in the crowded wards” of a “most efficient” kind during the US Civil War. Theo McDonald has documented the important role played by nuns. He noted that they advanced healthcare standards and posits there may be an actual decline in healthcare quality as hospitals replace nuns with secular managers.

Today, Peter Boylan highlighted, “Seven of the largest ‘public’ hospitals in Ireland are owned by private Catholic entities…Catholic control of the private healthcare sector is even greater. Twelve of Ireland’s 18 private hospitals adhere to Catholic ethos.” As found in Irish education, the Catholic Church played a substantial role in the historic foundation of Irish healthcare while persisting into the modern era in parallel to the improvement in Irish healthcare outcomes.

The Economic Dimension

After covering these two factors of the UN’s HDI, it is worth examining the final third. Gross National Income (GNI) per capita is the metric used by the UN’s HDI to evaluate the economic well-being of an average individual. In 2022, the UN’s HDI used a GNI per capita of $87,468 for Ireland.

From 1990 to 2022, Irish GNI per capita grew by 255 percent, about 3 to 4 times the growth of very high human development countries and the world average. In the same period, Irish expected years of schooling grew by 51 percent and Irish life expectancy grew by 11 percent. It’s clear that Irish GNI per capita greatly contributed to elevating Ireland’s overall HDI score. With that being said, over the past decade Ireland’s economic metrics have been called into question for being deceptive and perhaps much lower than suggested.

Figure 7

While the past decade might warrant scrutiny, it’s clear that Ireland still grew tremendously and well above its peers beforehand. From 1990 to 2000, Ireland grew 82 percent in GNI per capita compared to 17 percent for very high human development countries. However, in 1990, Ireland’s GNI per capita was already close to that of countries with very high human development at less than 12 percent while 154 percent above the world average. Although much has been made over Ireland’s relatively recent economic growth, once again, we see a pattern of Ireland not being as bad as narratives suggest.

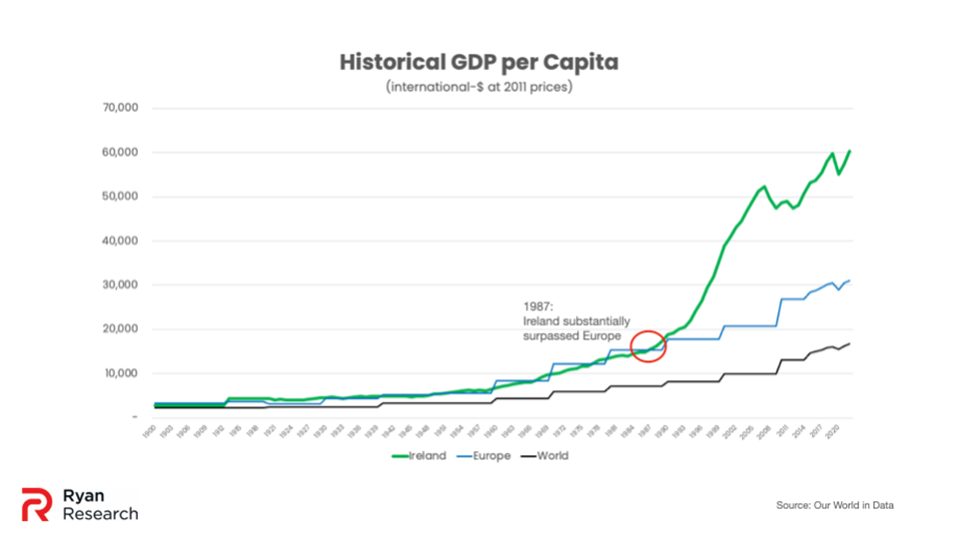

Using historical GDP per capita data as an approximate substitute for GNI per capita, Ireland closely tracked the average of European economic growth from 1900 to 1987. It is only after 1987 that Ireland’s economy drastically increased well past the European average. If judging Ireland by the context of its peers being the continent of Europe, the evidence doesn’t support the claim that Ireland was substantially worse than the average of its peers. When splitting between western Europe and eastern Europe, Ireland falls at about the midpoint between these two regions.

Figure 8

Is it fair to compare Ireland strictly to western Europe vs. all of Europe? In one sense, yes because Ireland is the furthest western country in Europe. In another sense no, because Ireland has had a few handicaps. One, the older imperial oppression of Ireland resulted in unfortunate conditions that prevented Ireland from developing at the same starting points or as quickly as the rest of western Europe. Two, besides outright theft, slaughter, and impoverishment, England placed specific legal prohibitions on Ireland that restricted its ability to industrialize its economy. Third, after independence Irish policy-makers were slower to crystalize correct economic policies that would have developed the economy faster. The East Asian Tiger economies figured those policies out much quicker after they received independence for comparison. Of course, it’s also the case that Eastern European countries suffered under brutal Soviet oppression until 1990, while we were free to trade.

Despite these challenges, Ireland still outperformed the eastern European average, a region that offers a more relevant comparison, in my opinion. As previously mentioned, Ireland kept pace with the overall European average, which, given its disadvantages, is a significant achievement. At the very least, Ireland performed adequately and cannot be so easily criticized. However, Ireland’s economic progress lagged behind its advancements in health and education, both of which surpassed peer nations much earlier. While Ireland’s economic development was reasonable compared to other countries, it fell short of its own potential. What prevented Ireland from fully realizing its fullest potential?

Trinity Business School Professor Frank Barry, in his book Industry and Policy in Independent Ireland, 1922-1972, offered an interesting observation that may shed light on why this lag occurred. Barry wrote that the Irish business elite was “predominantly Protestant and unionist. That the business establishment inherited by the new state differed from the majority of the population in these respects would impact economic policymaking well beyond the formation of the first Fianna Fáil government in 1932…The sectarian divisions in Irish business life would persist for many decades into the future.”

Barry used Irish banking as an example of this dynamic. “Six of the nine banks operating in the Free State area…were also unionist in ethos.” As late as the 1890s, the Bank of Ireland’s entire staff “belonged to the Church of England.” Barry noted that this non-Catholic pattern “prevailed across the rest of the financial sector.” Barry also analyzed 44,000 workers employed in large firms and found that “more than three-quarters were in businesses under Protestant and unionist control.” In a country where the vast majority of the inhabitants are Catholic, this would seem odd. It was even more bewildering as the trend continued well past 1922.

Barry noted, “Businessman Michael Smurfit recalls…that there were many companies, even in the 1960s, where Catholics could never join the management team.” It took many years for Ireland’s business elite to reflect what the country looked like. For example, while founded in 1783, the Bank of Ireland’s first Catholic CEO was in 1991.

It’s worth wondering if there is a causative connection there. It was demonstrated that Catholics managed the two other aspects of healthcare and education in Ireland with impressive performance. The third economic aspect, which lagged the other two, was firmly outside the control of Catholics. Protestant business elites inherited economic logics from the imperial days and weren’t as keen for radical changes to Ireland’s economic structure. This was compounded by Protestant antipathy to Catholic interests — interests that Protestants, historically, never considered aligned with that of their own. Perhaps, it is not that Catholicism in some abstract way divorced the Irish from a Protestant work ethic that resulted in a dreary and drab economy, as many conventional and popular writers often suggest. Perhaps, it was Protestant management of Ireland’s economy that stymied its potential for so long.

Of course, the use of the descriptor of “Protestant” has more to do with its relation to Unionism and the legally privileged status of the material heirs to English conquest in Ireland than the intricacies of religious doctrine. Thus, this isn’t a criticism of religion but the stratified elite class who had separate ideologies and interests to the “Catholics.” Similarly, “Catholics” can be used as a descriptor for the native population of Ireland that were historically oppressed by the former. Although there are exceptions to fitting unique individuals into each religious-political category, it does not disprove the general rule that the categories are containers for the definitions explained above.

Protestants represented a political class of people that derived their privileged status from conquest and oppression of the native Irish. It is obvious that their material interests were in conflict with that of the Catholic population and so they would develop ideologies that maintained their interests. I believe that these developed ideologies were the main reason for Ireland’s economic lag, a lag that was only compounded by Irish businesses preventing mobility up their ranks.

Conclusion

Evidence shows that Ireland’s past was not as harsh as some narratives claim. Secular liberalism’s contribution to progressing Ireland in the UN’s designated development metrics of health, education, and economy was minor relative to the much earlier contributions of the Catholic Church. Ireland was already fairly developed at the dawn of secular liberalism in 1990.

The Catholic Church was most responsible for managing hospitals and schools, dating back to the 19th century. Their performance assisted in driving progress to the point that the Irish had higher measurements in health and education than their peers much earlier than 1990. Even today, with Irish schools still largely under Catholic administration, Ireland was ranked 9th in the world and 2nd in Europe for its Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) standardized test scores.

With calls from the likes of Paul Murphy TD to abolish Catholic administration of schools, the Irish public should consider the phenomenal functional results of the Catholic-run school system. Is it truly a wise decision to discard the system that made the Irish one of the most educated people in the world? Paraphrasing G.K. Chesterton, “do not remove a fence until you know why it was put up in the first place.”

Finally, the Irish economy fared well for all its handicaps but didn’t mirror the better performances of health and education. The economy was the only aspect that was not under Catholic administration but rather, for a considerable period, under a minority of Protestant elites. Such a dynamic persisted after independence and it is arguable that this problem was not resolved until decades after 1922. Better representation of Catholics among Irish business elites could have likely progressed Ireland’s economy sooner and faster.

There is no excusing the sins and errors of men and women who acted within Catholic institutions. It is also fine to debate the role of religion in society, especially in services usually provided by a state. But rational debate cannot give way to polemical hyperbole and outright misinformation by certain sides. Even if the Irish citizenry voted to end all of the Catholic management of schools and hospitals in a future referendum, the historic role the Catholic Church played should still be celebrated and honored in Irish society rather than vilified.

Any fair person can see that the Catholic Church assisted in progressing Ireland and that contribution should not be neglected. By acknowledging this and the data discussed in this article, Ireland’s historic image can be seen in a more positive context. Rather than insult the collective self-esteem of the Irish people, a more positive narrative can provide more confidence.