On Saturday we examined the background to the Government’s decision to introduce Direct Provision amid growing concerns about evidence of abuse of the system by people not found to be genuinely in need of protection.

Today we are examining the background to another controversial event of the 1997 – 2007 Fianna Fáil/Progressive Democrats administrations, the 2004 referendum on citizenship.

The records cited were secured by Ken Foxe of The Story.

Among the possible explanations for the vast increase in the numbers of people claiming asylum was, as per a note to the Cabinet from Minister for Justice John O’Donoghue of September 1, 1999: “The recent granting of residence to a large number of parents of Irish born children, the majority of whom are asylum seekers.”

The lack of safeguards regarding citizenship was widely broadcast, and it was noted in the Government papers that such publicity was a factor in both attracting people and in severely limiting the state’s capacity to deport those found to be in the state illegitimately if they sought to avail of the loophole.

In a key memorandum from the Department for Justice of December 13, 1999, O’Donoghue set out his determination to tackle both the exploitation of the existing weakness in the citizenship laws, and the barriers to deportations. However, the section explaining the need for this in specific relation to the birth of children is entirely redacted.

A memo from Tánaiste Mary Harney, while leaning towards the free market view of labour migration, sought to balance that with a broader perspective. The question as to whether there ought to be any “societal” criteria governing the administration of the Irish state than economic growth is rarely asked. This is still the case for anyone of Harney’s equivalent status among the leaderships of any of the main government or opposition parties now.

Following the 2002 general election, Harney’s Progressive Democrat colleague Michael McDowell was appointed as Minister for Justice. On February 11, 2003, he submitted a memo to Government on the issue of Irish born children of asylum seekers.

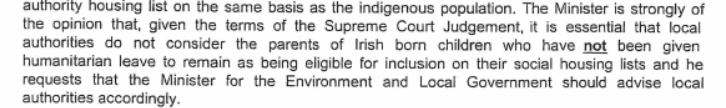

It made specific reference to a letter sent to him by the Masters of the Dublin maternity hospitals, and also to an important Supreme Court judgement of January 2003.

If a Minister now was to offer the same advice to local authorities he or she would likely be hounded out of office. We have now reached the stage where every party in Leinster House supports the granting of social housing to every asylum seeker, even before they have had their applications fully examined and approved.

Interestingly, the term “anchor baby” or “anchor child” was first coined in Ireland in relation to the court case referred to by McDowell. Although it has subsequently been used by opponents to claim that the restriction of citizenship rights was “racist,” the term was introduced into Irish legal and public discourse by Bill Shipsey who was Counsel for the appellants in the High Court case taken by the Roma and Nigerian fathers of children born in Ireland against their deportation.

This was referred to by Supreme Court Justice Adrian Hardiman in the judgement of January 2003.

The Irish born child was described by counsel for the appellants as “the anchor child”, presumably because he or she is seen as the anchor securing the rest of the family to this country. The birth of such child was contended to have a dramatic effect on the position of family members who were, at the time of the birth, liable to deportation. It is said to make such deportation virtually impossible since (again in the words of counsel for the appellants) “the immigration stork has landed”.

In his decision Hardiman stated that if it was conceded that the birth of a child

“effectively confers a right to remain indefinitely in Ireland on the parents, and any brothers or sisters, of the Irish born child,” then “this right, if it exists, would be unique in the world. But it is said to follow, inexorably or virtually so, from the child’s Irish citizenship and from the constitutional status of the family.”

Justice Susan Denham was quite clear too about the legal and possible constitutional implications of the claims. She said that

“the parents in these cases, who are not Irish citizens and have no right of residency in Ireland, cannot themselves decide to be Irish citizens or decide to reside in Ireland. Such decisions are for the appropriate governmental authorities to make in accordance with law.”

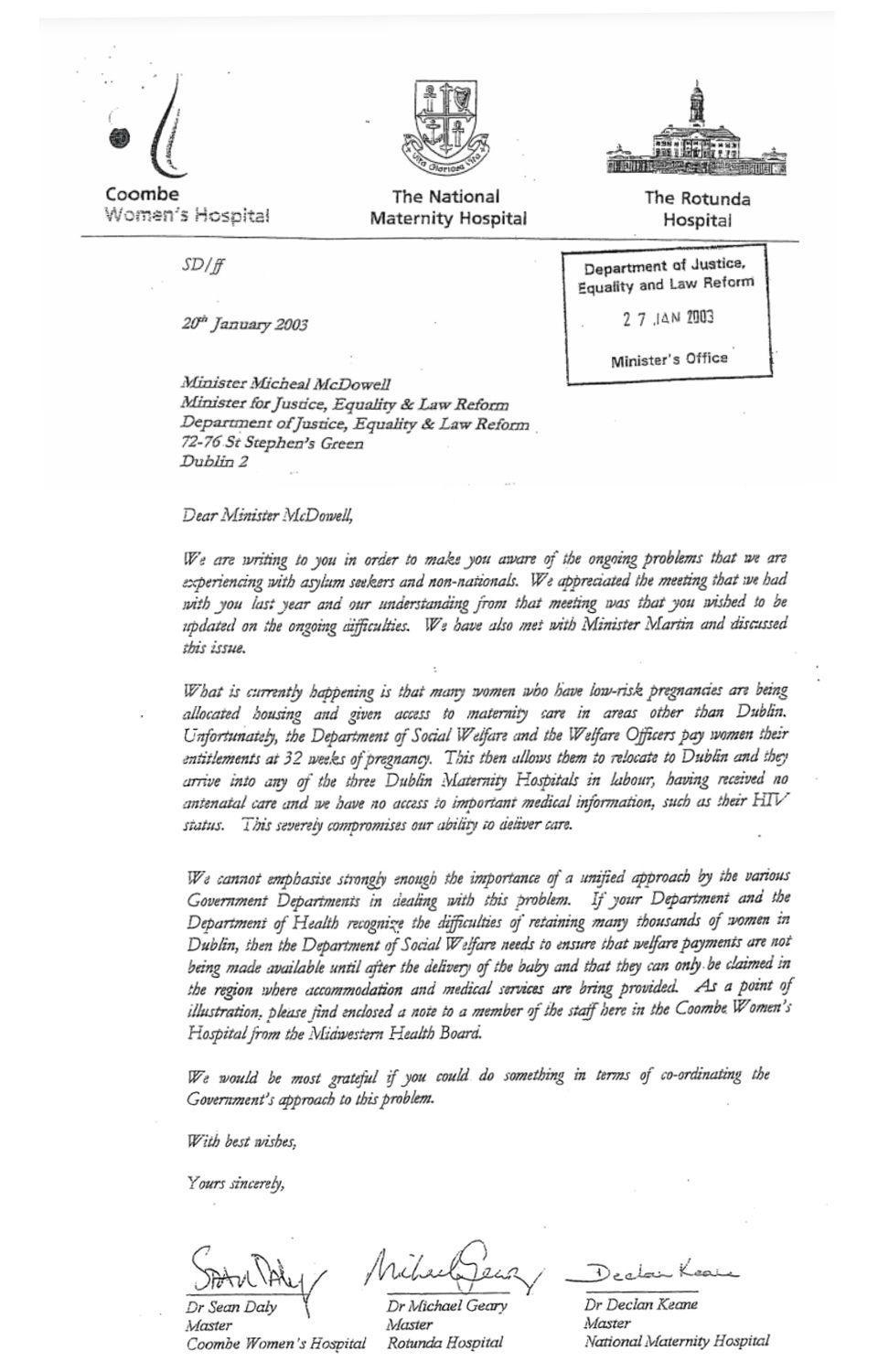

The other part of McDowell’s memo, and one that excited subsequent controversy when he spoke about it publically, was his reference to the concerns expressed by the Masters of the Coombe, Rotunda and National Maternity hospitals. They had written to the Minister on January 20th. While they later attempted to distance themselves from McDowell’s claim that their concerns had influenced the decision to bring forward legislation, their letter speaks for itself.

The state then clearly had no option but to seek to legislate in order to address this absurd situation and to do so they required the approval of the citizens, which they overwhelmingly secured in the referendum held on June 11, 2004. The proposition to change the Constitution by means of amending the criteria for citizenship was approved by 79.1% of those who cast a vote.

It is important to recall all of this because the current narrative is that the decision of the citizens in the referendum 2004, as well as the consequent Government legislation, were somehow illegitimate or motivated by ignorance and/or racism.

That narrative appears to be shared right across the political establishment. Not even the leader of Fianna Fáil, Micheál Martin, who was clearly behind the decisions then, has defended the government of which he was part.

Martin was then Minister for Health and when the masters of the maternity hospitals disputed McDowell’s claims regarding their interactions, Martin stated that he was surprised by the doctors’ claim, made in March 2004, given that it was they who had requested the meeting with McDowell.

Given the failure to properly manage the asylum crisis over the past two decades, and given the relentless undermining of even the constitutional protection inserted with the support of the citizens in 2004, any attempt to revert to the complete free for all that pertained up to then at the very least needs to be put back to the citizens in another referendum.

That is unlikely to happen for two reasons. Firstly, all recent opinion polls on the issue of asylum seeking have indicated that the public is at odds with the political, NGO and media elite on asylum seeking.. If the people oppose current government policy, it is unlikely that they will be asked to express their views in a referendum.

Secondly, the overwhelming political consensus that exists on the issue across that elite means that they likely believe they can continue to move towards an even more liberal asylum system without ever having to formally set aside the 27th amendment to the Constitution.

It is interesting then to cast back to the period a quarter of a century ago when bogus asylum seeking first became an issue. Not least of all to contrast the different approaches taken by those with the power to do so then in comparison to what has pertained over the subsequent years.