Government papers from between 1998 and 2003 reveal that the Irish state was well aware of the dangers posed by Ireland’s liberal asylum system. They also show that those warnings were either ignored or preventative measures taken then were later set aside.

Documents secured by journalist Ken Foxe of The Story relate to the initial Cabinet decision to introduce Direct Provision as a direct response to fears that the system was being “overwhelmed” by opportunistic economic migrants. The papers released to Foxe also provide an interesting insight into how state policy was formed without the overweening influence of advocacy NGOs who played such a major role in the decision to abolish Direct Provision.

A coalition of Fianna Fáil and the Progressive Democrats led by Taoiseach Bertie Ahern was in power over that period and the two Ministers were John O’Donoghue and, after the 2002 election which returned the two parties, Michael McDowell. The crisis created by the influx of, what were overwhelmingly believed to be, bogus applicants and the abuses noted of the system led directly to the 2004 referendum on citizenship.

A memo of August 28, 1998, from the Department for Justice states that “There are good grounds for believing that the nature of welfare provision in Ireland is acting as a “pull” factor, irrespective of developments in the UK. There is already clear evidence that a high proportion of asylum seekers arrive here from the UK.” The British Labour Government was at that time overseeing the passage of the Immigration and Asylum Act (1999)

The move by the UK towards “non cash support” would exacerbate that, so it was vital that the Irish state act quickly as otherwise there would be “very significant displacement effects for Ireland. Under such circumstances, persons whose principal motivation is economic and who might otherwise have applied for asylum in the UK are more likely to be attracted to Ireland’s continuing cash based approach.”

The context of this was that there were at that time 6,000 persons in asylum maintenance and that was forecast to grow by around 4,000 per year after the tightening up of provisions in the UK. The cost of that maintenance would increase from £60 million to £100 million. Since then, Direct Provision alone has cost the state well over €1 billion. That is apart altogether from the other costs and negative impacts of asylum seeking here.

The contrast between the realism and language of the considerations contrasts sharply with the later wholesale adoption by the political establishment of the language and approach of the advocacy NGOs. In his Foreword to the White Paper to end Direct Provision, Roderick O’Gorman claimed that DP had only meant to be “temporary” and that it had proven to be “expensive, inefficient and ill-equipped.”

The adoption of the advocacy NGO narrative was no accident given that the period coinciding with the attempt by the state to tackle bogus asylum seeking saw a huge disbursement of money to the sector by Atlantic Philanthropies. This amounted to over $3 million between 2002 and 2004 and a further $84.7 million in the years after the passing of the Citizenship referendum.

That succeeded not just in creating a large, and now largely taxpayer funded, activist sector committed to overturning both the decision of 80% of the electorate in 2004 but also to reverse the decision of the Government to introduce Direct Provision.

Huge resources were invested in the campaign, which was supported by every establishment party from Fine Gael to Sinn Féin and the communist left, to ensure that Direct Provision was abolished and replaced with a new system that, as the vastly increased numbers of asylum seekers here shows, is clearly already acting as a new and even great “pull factor.”

The complete lack of reality underlying the NGO scripted White Paper is indicated by the fact that when it was published at the beginning of 2021 its authors were basing their plans on the assumption that there would be 3,500 applicants for International Protection each year (p91). In 2022, there were 13,651. That increase being in no small measure the consequence of the helpfully translated and widely disseminated Pollyanna open doors policy adopted by the Irish state. They also claimed that one third of the applicants would be children. The figure has been around 18%.

Some of the other considerations informing the Government decision to introduce Direct Provision were that it was less vulnerable to fraudulent claims on the social welfare system, and that it would also “reduce the potential for trafficking.” Unfortunately, the belief that DP would prove to be “short-term rather than long term in nature” was undermined not least by the backlash against; it not to mention court decisions which made it more difficult to tackle bogus asylum claims.

The government in 1998 and 1999 was clearly feeling the pressure. “The situation is now at crisis point” was the comment on the situation regarding accommodation. Numbers arriving were increasingly alarming and it was reported that in inner city Dublin this was “adversely affecting the availability of both emergency and private rented accommodation for indigenous people (sic), both homeless and other wise and is considered to be a factor in the escalation of rents.” A note to the Cabinet of September 1, 1999, does not pull any punches regarding the possible reasons for the increase.

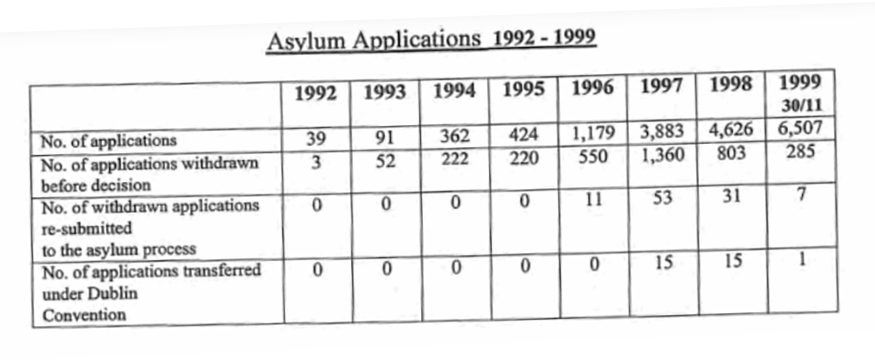

The statistics show that in September 1999 the numbers who had arrived was double that for June, and almost as many as the figure for the entire year in 1996. Numbers for the whole of 1999 were forecast to be over 7,000 compared to 4,626 for 1998. The countries of origin were overwhelmingly people travelling from safe countries such as Romania and Nigeria.

There were, as there still are, few deterrents as no deportations could be carried out due to a court decision that they were unconstitutional. That situation was only rectified by the 1999 Immigration Act but the documents later refer to the ongoing frustrating of efforts to deport those who had been found to be in the state illegally.

The numbers who were found not to be genuinely seeking asylum were telling. Of 5,087 individuals whose cases were heard substantively between May 5, 1998, and November 30, 1999, 89.6% were refused at first stage. That was of 7,991 interviews that were scheduled but of that number 2,954 either failed to appear or otherwise withdrew from the system. So the percentage of genuine applicants was much lower than 10%.

That disappearance into the underworld network of illegal immigrants, along with all the other obstacles placed in the way of dealing with this through deportations, as well as the escalating numbers attracted here, had already created a backlog of more than 6,000 cases by the end of 1999.

That situation has only worsened, and the state’s sole response has been to basically accept this by either ignoring the fact that illegal immigrants are living openly here – some ironically as “anti-racist” activists; the liberal dispensing of citizenship, and of course a mass amnesty for anyone who has not availed of other opportunities to extend their stay here.

The papers secured by Ken Foxe shed an interesting light on the background and origin of the current mess. We shall be returning to them to explore the reasons why the state decided to tackle one of the more blatant abuses of the 1990s and early 2000s which led to the 2004 Citizenship referendum.