Dublin City Council’s City Manager, Owen Keegan, is not, of course, the de jure King of Dublin. The last man to hold such an office was Ascaill Mac Ragnaill, who was shamefully deposed by the English in 1170, and beheaded a year later in a failed attempt to regain his throne. Keegan is, however, effectively the de facto King of Dublin: He has a job, in essence, as long as he wants one, and while he is in theory answerable to the City Council, the relationship between Monarch and legislature is much more like that between a Medieval King and his cowering parliamentarians than it is like that of a modern constitutional monarchy. If you wanted to sum up the relationship, it would be like this: Keegan sets the policy, and the councillors are elected by the public to complain about it, and “call for him” to do things differently. That’s not perfectly true, but it’s not an unfair summation, either.

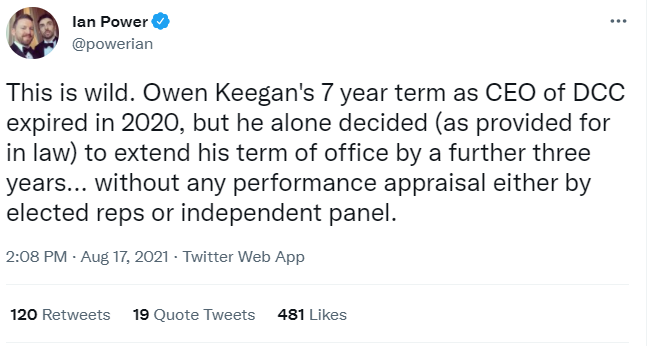

Indeed, even in terms of his own employment, Keegan, and Keegan alone, sets the rules:

Which means, of course, that he need not fear unpopularity for statements such as this:

HOMELESS CHARITIES HAVE today criticised Dublin City Council’s chief executive Owen Keegan who yesterday suggested that “well-intended” homeless volunteers are sustaining people sleeping in tents on the streets of the capital.

Keegan told the programme that anti-social behaviour is a concern and said that the proliferation of tents in Dublin is adding to this.

“There are other aspects, like the proliferation of tents – and I’ll get into trouble for saying this – but we don’t think people should be allowed sleep in tents when there’s an abundance of supervised accommodation in hostels.

“We’ve had up to 100/150 beds available every night for homeless people, and we would have thought that it’s not unreasonable that in those situations, if you’re homeless, you’d go into a professionally managed hostel.”

To be clear: He has a point. In an ideal world, nobody would be sleeping in a tent. Even in a less than perfect world, tent sleepers would be in a bed, in a hostel, and not out in the cold, on the hard concrete of Dublin’s streets. That’s not an unfair observation.

The problem, of course, is that it is his City. Keegan is the man in charge, and has been for approaching a decade. The councillors deserve their own share of the blame for the housing crisis – especially their repeated decisions to block new housing builds – but the operation of the city’s homelessness services is the responsibility of the council administration, which Keegan is in charge of. If those homelessness services are failing to provide emergency accommodation which is more appealing than a tent, then Keegan needs to take his share of blame for that. Peter McVerry yesterday, for example, was out to point out that a big issue with the hostels is the amount of drug use in them, and that people who want to stay clean of drugs often prefer tents, where they can be away from that culture. That is understandable.

It is also unfair, and cruel, to lay the charges he does at the feet of the homeless, especially while discussing anti-social behaviour. A great deal of anti-social behaviour is committed by people with homes. Often, homes with parents in them. Gangs of young people, frankly, are much more intimidating for most people than a homeless person in a tent.

The main problem with Keegan, though, is that he is entirely unaccountable. He is the most powerful man in Dublin who is not a member of the cabinet. His decisions have vastly more influence over the city than the votes of councillors do, and yet, the public cannot remove him, or hold him to account in any way. For years, for example, his council has pursued an aggressively anti-car policy. That may be popular and right, or unpopular, and wrong. The point is that nobody has any say in the matter.

In a democracy, things should not work like this. Dublin probably needed a King in 1170. It does not need one today. Mr. Keegan’s comments yesterday display the kind of tin-eared tiredness, and lack of understanding, that comes from being in a position of power for far too long. It’s time for him to abdicate.