More than 2,000 deportation orders have been revoked since 2018 – in some cases due to the amnesty granted by Minister Helen McEntee for “undocumented persons” – according to figures from a document seen by Gript.

The document records that, in the last three years, there were higher numbers of revoked deportation than actual deportations. The figures cast further light on the issue of deportations from the Irish state.

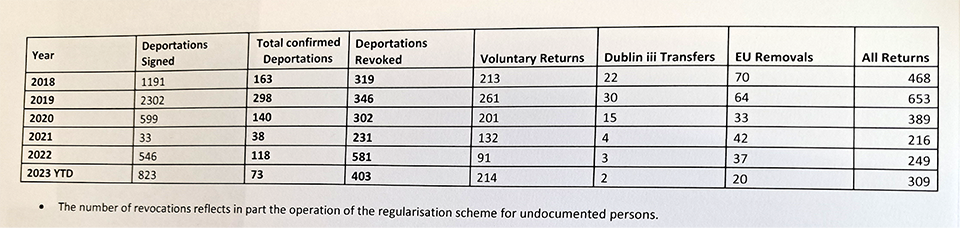

The table below shows that, between the beginning of 2018 and the date on which the information was compiled, 2,182 deportation orders had been revoked.

There is no indication as to the date on which those orders were originally issued and signed, and as has been pointed out previously, there are outstanding orders on people who have been living in Ireland for many years.

The document refers in a footnote to the fact that the “number of revocations reflects in part the operation of the regularisation scheme for undocumented persons”.

That is interesting as it suggests that some of those who applied for and have been approved under the amnesty scheme that began in January 2022 and was scheduled to end in June 2022, were persons who had previously been issued with a deportation order.

These were people who had either clearly failed to comply with an undertaking to leave the state voluntarily or whom the authorities had not compelled to leave. They had thus presumably been living illegally in the state for the period prior to their application for amnesty.

Which raises a whole series of questions as to how they managed to avoid detection over that period. Apart from the fact that they had succeeded in doing so and thereby breaking the law, they had surely thereby compounded whatever reasons which had led to their being issued with a deportation order in the first place.

There is also a figure provided in the table on the number of “voluntary returns” of persons who have been issued with a deportation order. That has attracted controversy because there have been cases, including those reported by Gript, of persons who had agreed to leave but who were found still to be in the state.

The official Oireachtas research paper seen by Gript addresses the issue of voluntary return or “self-deportation” as it is known here. That paper points out that the latter term is not defined in Irish immigration law.

Furthermore, the document points out that under the EU definition of voluntary return that the person who agrees to a voluntary return must do so of their own “free will,” and without having to inform anyone as to the arrangements for this. In return “the formal issuance of a deportation order is avoided.”

Which not only appears to be naively absurd – a person subject to any other serious legal sanction is compelled to abide by such a sanction – but places far too much trust in the goodwill and cooperation of people. who have not only been found not to have any right to be resident in the state, but in some cases have been awarded a remission of sentence for serious offences on the basis of such a promise.

There is also the question as to whether someone who has been convicted of a serious offence, and that obviously applied in one of the cases Gript reported on involving a serial sex offender, there ought even be an option for voluntary return or “self-deportation.”

The relevant legislation which allows for voluntary return is the International Protection Act (2015), which in Section 48 specifically denies that option to avoid a deportation order if the person is considered to be either a danger to the security of the state; or to present a danger to the safety of the community because they have been convicted of a serious offence.

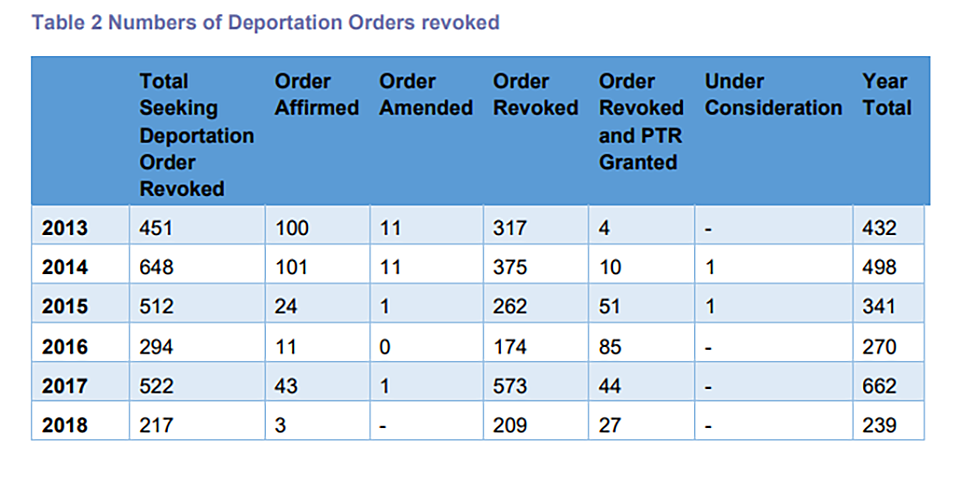

The Oireachtas research paper also includes statistics on deportation orders that were revoked between 2013 and 2018. As with other statistics on deportations, the figure given in this paper for orders that were revoked contradicts – or appears to contradict as we do not know what exactly explains the discrepancy – the figure that is cited in the table above from the Department of Justice.

In the document screenshot shown at the outset of this article, the number of deportation orders revoked in 2018, the only year that is included in both sets of data, was 319. The corresponding figure in the Oireachtas research paper above is 209. What the table also shows is that of 2,644 deportation orders whose revocation was sought between 2013 and 2018, that just 282 or 11%, were affirmed.

In contrast, an astonishing 1,901 of the appeals to have an order were revoked. That was of a total of 2,442 cases that were dealt with within the calendar years referenced. Which would mean that 78% of such appeals are likely to be successful. The percentages involved all confirm, even given the discrepancies, the extremely low number of deportation orders that are enforced.

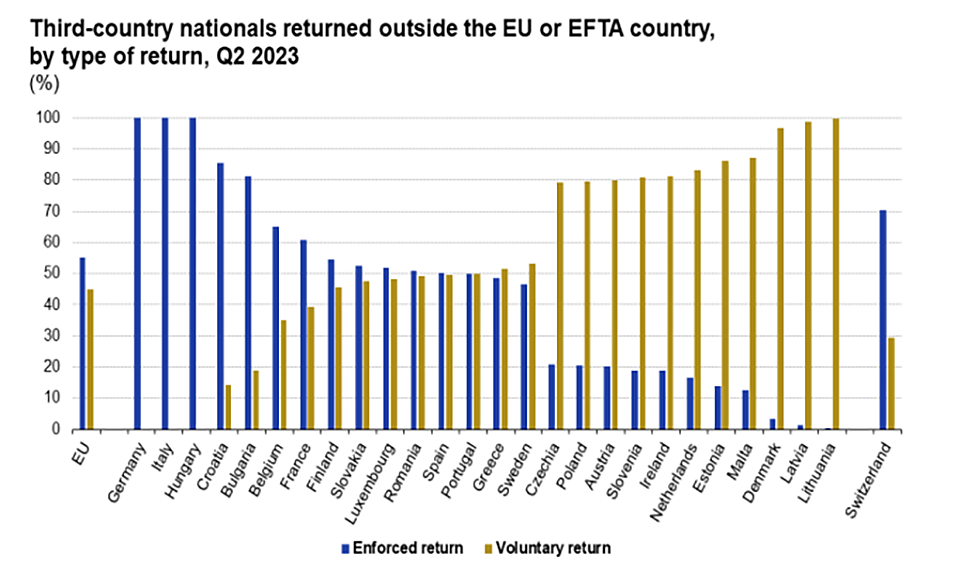

The paper notes that the Irish state is at the lower end of the numbers of deportation orders that are actually enforced rather than someone who might be subject to such an order being allowed to voluntarily leave the state.

The only evidence in the paper that the Irish state is taking the issue of illegal immigration more seriously is that the number of deportation orders issued in 2023 was 713. Significantly, 209 of the orders were issued against persons who claimed to be from Georgia. On the downside just 57 of the 713 orders were affected.