Twenty nine special trains were put on to bring supporters from all parts of the country to Croke Park for the 1923 football final on September 28, 1924. This was before the famous ‘night train’ from Kerry made famous by Sigerson Clifford, and chaps in Ardfert could rise at a civilised hour in time for the 7.25 train that journeyed on through Tralee and Killarney.

The Irish Independent predicted that the final would be a classic. Kerry’s recent sojourn in the doldrums, not having won an All Ireland since 1914, was put down to the effect of “troubled times” and a lack of funds although they were believed to have made great progress in training. Dublin had the more experienced team with a forward line that was described as “fast and scientific.” Freeman’s Journal said that few counties appearance in a final “excites a greater stir” than Kerry and attributed this to their great battles with Kildare in the 1903 final, which Kerry won only after three games.

The Kerryman published the day before the final provided quite detailed pen pictures of the team. Their average age was 25, with the youngest player, Paul Russell, being only 18. Russell played in seven All Ireland finals and was only on the losing side once, in 1923. He was just 27 when he won his sixth medal in 1932. Their weights are also included and averaged around 12 stone which suggests that they were smaller, or at least less well nourished, men than modern footballers.

P.J O’C continued to apply the sports psychology. According to him, Kerry were only “partially trained”. The Dublin forwards would be playing for frees, from which they were “deadly accurate.” He also described Dublin as a “rough team” that would employ any means necessary in order to win. He also returned to his pet hate of the oul’ hand passing, which, “while it might appeal to the gallery, it is not football.”

A poem published by The Kerryman on the eve of the final struck a more poignant note:

Let not politics divide you,

When the foe line up beside you,

Bury deep that piercing hatchet,

That has rent our land in twain.

The Kerry team spent the night before the match in Barry’s Hotel on Gardiner Place, having been entertained on the Saturday in Dunboyne House where they were called upon by Eamon De Valera, perhaps in gratitude for their having refused to play until he was left out of prison. Presumably he, as a rugger chap, did not share with them his allegedly low opinion of the game of Gaelic football.

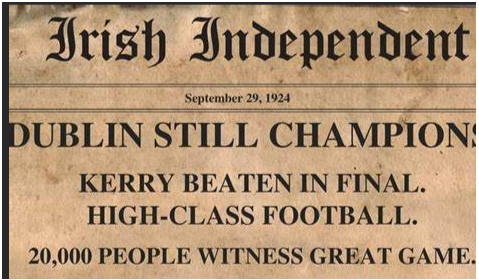

A big crowd for the times turned up for the final. GAA records give it as 20,000 with a gate receipt of £1,622. However, Freeman’s Journal estimated the crowd at between 35 and 40,000 and described Hill 16 as a “huge living pyramid”. Food for thought for those who seem to believe that the Hill was spawned by imitation of the Kop or the Stretford End. The crowd was described as good-humoured and well-behaved. There was nothing in the way of rough conduct despite the fact that “the enormous multitude was strongly divided into partisans of Kerry and Dublin and did nothing to conceal their partisanship …such a concourse of red enthusiasts as has seldom, if ever, been surpassed in Irish football history.”

Dublin 1923

The final has sometimes been cited by GAA historians as evidence of the return to normality following the Civil War and so it was also seen at the time. “Political and party distinctions, too, seemed to have been wiped out for the occasion, and one literally saw all sides in the gathering.” However, as with the false reports of the meeting between ‘Free’ Murphy and Mulcahy in Tralee, such must be taken with a pinch of salt. Kerry and Dublin Free Staters and republicans hardly had any more regard for one another because they all happened to be shouting for the same team, or that they all happened to be at the one match.

The game itself was marred to a certain degree, as September finals sometimes were, by a strong wind. Dublin began stronger but failed to score. Joe Stynes missed an early chance and other attacks finished in wides by Johnny Synnott. Kerry’s first point, after 12 minutes, came from John Ryan after he received a pass from John Joe Sheehy. Kerry began to get on top and Ryan kicked another point on 20 minutes to put them two ahead.

An outstanding feature of the match was the midfield tussle between Dublin’s Johnny Murphy and Kerry’s Con Brosnan, and it was Brosnan who scored the first goal which came from a 50 yard free that beat Johnny McDonnell in the Dublin nets. McDonnell had also been the Dublin net minder on Bloody Sunday, November 1920, having earlier that day taken part in the executions of the Dublin Castle spies in the city. Dublin responded and when Stynes was fouled Johnny Synnott kicked Dublin’s first point from a free to leave the score 1 – 2 to 0 – 1, to Kerry’s advantage, at half time.

Dublin also began well after the break and this time they made use of their possession. Having hit the crossbar in the first few minutes, Pat Kirwan of Keatings scored a goal after five minutes. There was now only a point between the teams but Kerry extended that briefly with a Sheehy point on 14 minutes. Dublin struggled to get the upper hand and there were only ten minutes remaining when McDonnell kicked their first point of the half. Kerry objected strongly as Con Brosnan had been knocked out as Dublin advanced and he lay unconscious on the ground, but the score stood.

Johnny Murphy brought Dublin level with five minutes left on the clock and Stynes gave them the lead following a move that involved Larry Stanley and Martin Shanahan of O’Toole’s other local rivals, Mary’s of East Wall. Dublin’s superior fitness seems to have told in the latter stages and Stynes extended the lead to two and Dublin also had a point disallowed for an infringement in the parallelogram.

The general feeling was that Dublin had deserved to win, but P.J of The Kerryman was not convinced. Sarcastically he claimed that Dublin had evinced the “most kindly feelings” for the Kerry lads. “They got so fond of them…that it was nothing unusual to see a Dublin player clasping a Kerryman round the neck, playfully pucking him in the back, catching him by the hand or jersey in order that the man for Kerry would not hurt the ball.” He further claimed that a Dublin man had been in the square when they scored their goal and that the game should have been stopped when Brosnan was knocked out. Even the referee’s hopping of the ball favoured Dublin. Kerry, in contrast, had played “clean football.”

Kerry avenged their defeat in the 1924 final, held on April 25 1925, and the great rivals would not meet again in a decider until 1955. Dublin’s fortunes declined dramatically after the early 1920s, winning just one All Ireland over the next 35 years, in 1942, before the great revival of the 1950s. In the intervening years they met a further three times in semi-finals with Kerry winning two, in 1932 and 1941, and Dublin the other, in 1934.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the relative rarity of championship encounters during the 30s and 40s, no other two counties could excite the pulse as much when they met and the 1955 final was watched by a crowd estimated at 100,000. Much of that could be traced back to the 1923 and 1924 finals and it was elevated to mythical status in the 1970s.

Kerry have enjoyed historical dominance, but that record has radically shifted towards the Dubs since 2011. Last year’s semi-final was won by Kerry in typically dramatic circumstances and no one will be expecting anything other than another epic. For Kerry it is a chance for them to win their second All Ireland in succession and most likely bring an end for once and for all to the greatest Dublin team of all time.

For the Dubs, it may well be the Last Dance before they exit the stage to join all the other storied ghosts of the past century and more.