Between the 17th and 19th centuries Ireland turned from a predominantly Catholic and Gaelic country (at the time the two things were so closely entangled they were politically synonymous) to one where it was illegal for the Irish Catholic to teach their children.

Gaelic culture was not only discouraged, but officially barred from all legal life and from all public institutions. It was a brave and rare official or person of property who maintained any form of Gaelic culture, and it was only done by keeping so far below notice that it never registered in the reports that circulated back to the castle in Dublin.

Prior to the 17th Century in Ireland, Gaelic culture was completely integrated into the political life of the country. Though political loyalty was not so straightforward, with many Anglo-Irish seeing their fealty as owed to the English crown, the dominant culture throughout all but a tiny scrap of land around Dublin known as the Pale, was thoroughly Gaelic. This was the case to the extent that, despite many efforts to separate the new Norman aristocracy from Gaelic culture through oath and law, the Norman Irish were disparagingly described as “more Irish than the Irish themselves”.

But while there was an exclusion of Gaels from the political establishment, Gaelic culture stubbornly held on.

The Gaelic language was spoken by the aristocracy, both Gaelic and Anglo-Norman; Gaelic poets, and arts were patronized by the Sean-Gael and the Sean-Ghall (the old Anglo-Irish families who came with the initial Norman invasions). The Sean-Ghall assimilated into the Gaelic way of life even if they had a loyalty primarily to the English crown.

This all changed radically in the 17th Century. The Tudor-initiated reformation tied religious identity with political loyalty and legitimacy. The battle of Kinsale gave the English a political momentum which left the Gaels and Sean-Ghall on the backfoot. Cromwell left the Irish aristocracy in political retreat and the loss of the Jacobite wars between James II and William of Orange ushered in the penal age. The penal age went beyond political eradication, and intended to implement the cultural death of Gaelic Ireland.

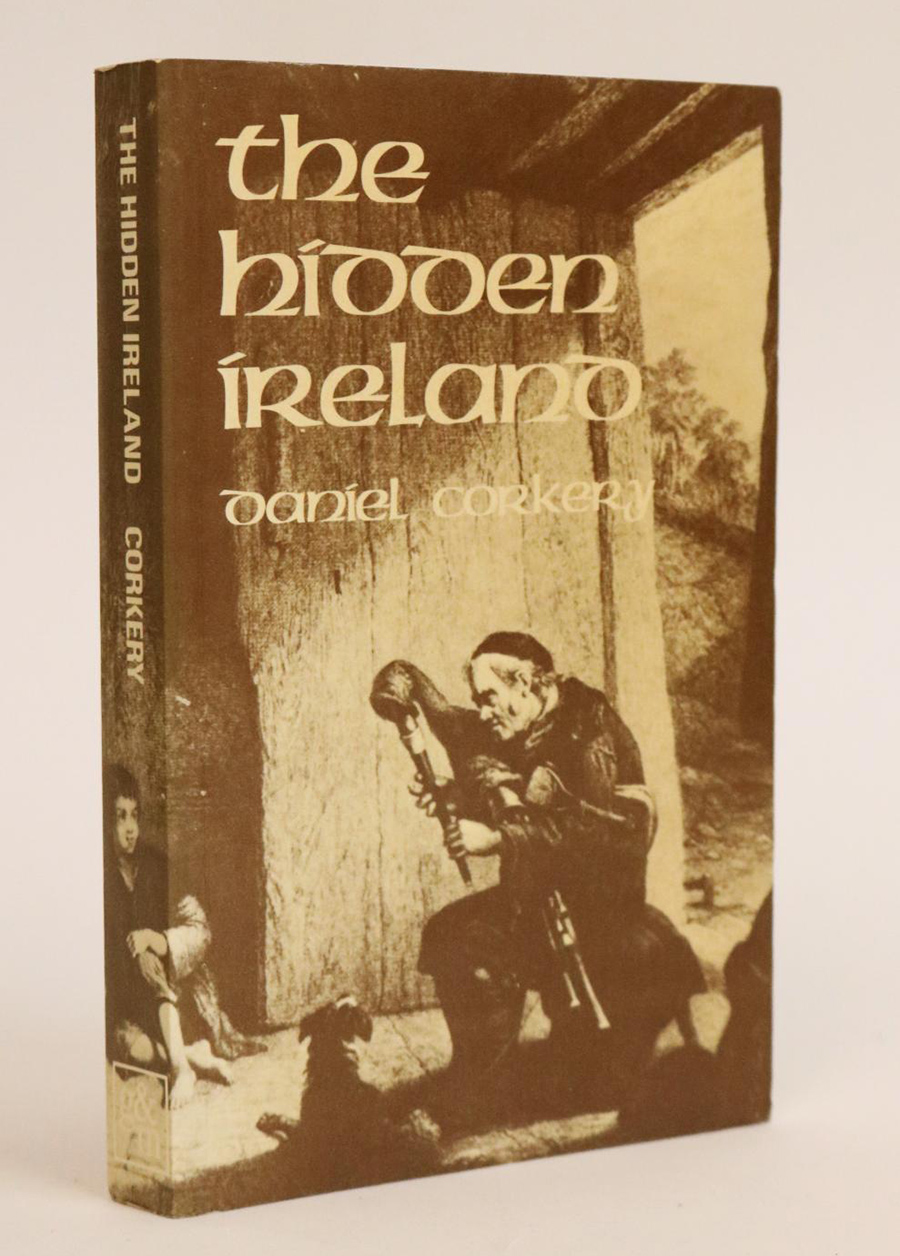

100 years ago (1924) Daniel Corkery published a fascinating book which shone a light on the Ireland that was formed and emerged from this period of cultural genocide.

The Hidden Ireland described an Ireland of grossly unjust paradox. An Ireland of two parallel worlds and cultures. The Ireland of the big house of the English-speaking landlord, and an Ireland of the impoverished bothán inhabited by the natives. It’s that hidden Ireland of the destitute and exploited tenant living in their tiny dwellings, who made up the vast majority of the country, and who were the inheritors of a rich linguistic past, that Corkery exposed to the newly-formed Irish state.

Before the “breaking” after the battle of the Boyne, Corkery says that it could be observed that between the house of the Planter and the house of the Gael there was frequently a similar reception for Gaelic culture and its exponents.

He accounts:

“It would seem that there was no other striking difference between the way of living in both classes of houses, except that the great stories of the Gael were naturally welcomed in one and thought alien in the other. The structure of life in West Cork was still so firm and self-contained that the change of ownership in the big house, like Castle Tougher, from Gael to planter, did not immediately make much difference in what its ancient walls looked upon day in and day out : it was only the flowing by of long years, that succeeded little by little in depriving Gaeldom of its vigour, in stopping up its numerous ways of manifesting openly what its ancient spirit brooded upon.”

A Gaelic poet, Aogán Ó Rathaille, visiting Castle Tougher in West Cork sometime after its passing from the possessions of Tadgh an Dúna MacCarthy who died in 1696, to the hands of a newly arrived Planter, describes a scene that was at this stage becoming rare. O Rathaille writes:

“Do mheasas im aigne is fós im chroidhe

An marbh do mharbh gur beo do bhí

Ag carbhas macra feoil is fíon

Punch dá caithiomh is brannda”

“I thought in my mind and in my heart

That the dead who had died were living

A youthful carouse with meat and wine

Where punch was enjoyed and brandy”

And he finishes with

“Sé Dia do chruthuigh an saoghal slán

Is thug fial I n-ionad an fhéil fuair bás

Ag riar ar mhuirear, an chléir, ar dáimh

Curadh nach fallsa mórchroidhe”

“It is God who has created the whole world

And gives us one generous man for another who died

Who makes gifts to families, scholars and Bards

A champion not false but greathearted”

This familiarity and acceptance of the local traditions and customs was a rare surprise, and Ó Rathaille would die a pauper just 30 years later. His poetry looked back with bitterness on the transformation of Ireland during his lifetime. Born into a world where Gaelic culture still had the respect of the established landowners, he saw that change dramatically to where nearly all the wealth of the nation was held by a class who despised the Gael.

He was born in 1670, close after the great genocidal campaign against the Gael by Cromwell, but during a short reprieve of the reign of James II in which the Sean-Ghall re-established political freedom.

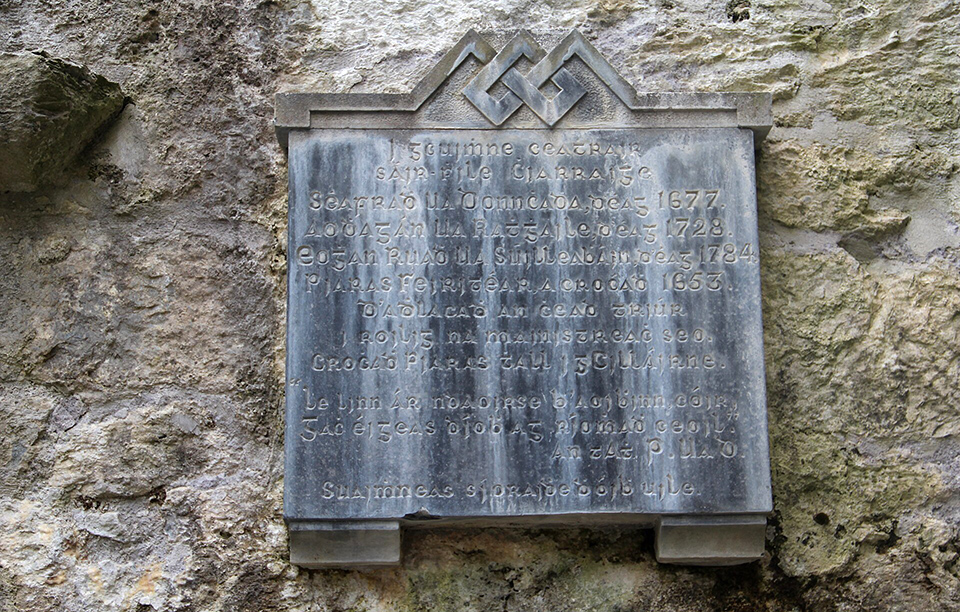

Corkery describes his youthful formation: “Growing up, not far from Killarney, the people’s imagination was still hot and bitter with memories of Cromwell. The boy must often have had pointed out to him that spot on Sheep’s Hill, in Killarney, where, only little more than twenty years before, Piaras Feiritéir, that chieftain poet, that gallant figure, was treacherously hanged, a priest and a bishop hanging with him.”

Ó Rathaille was clinging to a culture that was slipping from the grasp of the Gael. He wrote bitterly of this loss while hoping for resurgence.

Corkery puts this beautifully:

“The elegies recur to us as great litanies of racial sorrow: we are conscious of loud dark voices chanting vehemently the praises of the dead… His thoughts were all with the past as befitted one who was writing the elegy of the Gaelic race”

Within 20 years of his death in 1729, another poet was born in the same hills of Sliabh Luachra. Eoghan Ruadh Ó Súilleabhán, wrote with great wit but accepted his lot as a landless Gael. He was descended from the O’Sullivan Beare who escaped Bantry after Kinsale and made that terrible winter treck to Leitrim, shedding the weak and dying along the way. Eoghan Ruadh had all the learning in the world – and not a penny or a patch of ground to match it. His poetry was typical of his Gaelic contemporaries and embraced the life of a vagrant and the wit of the hearth.

His lyrics hold a more sanguine relationship with his low station in the eyes of the moneyed people.

“Iar gcaitheamh an lae más tréith nó tuirseach mo cnámha,” he says

“Is go n-abrann an maor nach éachtach m’acfuinn ar rain,

Labharfad féin go séimh ar eachtraigh an bháis,

Nó ar chathaibh na nGréig ‘san Trae d’fhúig flatha go tláith”

“At the close of day, should my limbs be tired or sore,

And the foreman gibe that my spade-work is nothing much worth,

Gently I’ll speak of Death’s adventurous ways,

Or of Grecian battles in Troy, where princes softly fell”

He was a spailpín who once found himself in trouble with the local landlord in Fermoy, and enlisted in the British army as a means of escape. He ended up in the royal navy fighting in an encounter between the British navy and the French in 1782 near Martinique. The victory was the greatest thus far in British naval history and Eoghan Ruadh wrote his only English language song accounting for it.

In a curious encounter, the admiral of the British fleet, Admiral Rodney, upon hearing the song asked to see Eoghan Ruadh and offered him promotion. Eoghan Ruadh asked for release from the navy and his commanding officer replied “anything but that; we would not part with you for love or money”.

Eoghan Ruadh muttered sullenly “imireochaimíd beart éigin eile oraibh” (I’ll play some other trick on you) in Irish and departed.

It’s strange to think that this rough-looking seaman was offered a fortune (from his perspective) for a poem in a language that would rarely pass his lips, while at the Irish fireside his most eloquent Aislingí were cherished by landless peasants who took hope from their refined artistry.

Later it is said that he blistered his shins with spearwort in an attempt to get the doctor to discharge him from the army. It worked and Eoghan Ruadh made straight for Kerry. He was only 36 when he was struck in the head with a fire tongs by a servant of a yeoman he had satired. With a grievous head wound, lying alone in a fever hut, he died of his wounds. In the final moments of his death he rose and took a quill and paper and started writing. His last act on this earth was to write the following lines:

“Sin é an file go fann,

Nuair thuiteann an peann as a láimh”

“weak indeed the poet

When the pen falls from his hand”

The picture of Ireland that Corkery paints is one of the Gael and a separate one of the Gall. The Gaelic-speaking Irish might visit the big towns and cities to ply their wares and sell their services but “they were nevertheless little else than exiles among the citizens.” Dublin, like many other towns of the planter had an “Irishtown” outside its gates where the Irish could go after curfew saw them turfed out of the city gates.

Corkery explains that:

“Gaelic Ireland, self contained and vital, lay not only beyond the walls of the larger cities, but beyond the walls of the towns… For Irish Ireland had, by the eighteenth century, become purely a peasant nation… its strongholds lay far away beyond the fat lands, hemmed in by the mountain ranges.” The planters, according to their own words “measured law by lust, and conscience by commodity.”

Corkery offers a fascinating picture of decay and a culture clinging on to its cultural heritage whilst being stripped of its possessions and rights. As he traces the lives of the poets he describes how their existence descended in stages.

The Bardic schools for over 1500 years provided the “one national force that overshadowed all others” and that was identified and attacked systematically first by the Tudors. The well-known literary exponent of English culture, the Tudor planter Edmund Spenser, saw that the bardic system was the source of Gaelic cultural vitality, and vigorously and viciously advocated its rooting out and destruction – for he correctly understood that it was the Bardic schools that provided the poets who not only recorded the histories of the great clans in poetic meter, but also preserved the brehon laws and acted as breitheamh (judges).

The Bardic schools were rigid scholarly instituitions with highly demanding standards of scholarship. Their eradication was a strategic project that was pursued with great animosity throughout the 17th Century.

By the end of the Cromwellian era the Bardic Schools were well and truly eradicated, and their cultural place was replaced by the courts of poetry. These were informal gatherings of poets, sponsored sometimes by a prosperous host, who would have seasonal meets in his own homestead or inn.

At these gatherings, new poems would be shared and relished, not by patrons who rewarded with wealth and administrative positions, but by enthusiasts of culture who could only pay with the hospitality of the occasion and appreciation of the art shared. As the 18th century wore on, these schools diminished and the poets who attended them died in worsening poverty. As the assets and wealth of the Gaelic hidden Ireland was extorted over the decades of penal laws, even the modest wealth of a poet inn keeper/farmer, such as Tadgh Ó Duinín, was sucked into criminal system of landlordism. The courts of poetry all around Munster lasted only a few generations after the fall of Limerick and the departure of the Wild Geese.

The gairmscoilleana (hedge-schools) provided income for these men for a time, but even that became an impossibility as Ireland entered the 19th century a bankrupt nation with the contrast of the ubiquitous tenant hovels and obscenely decadent landlord mansions. Corkery offers biographies of many of the Munster poets of the 18th Century. Aogán Ó Rathaille, Eoghan Ruadh Ó Súílleabháin, Seán Ó Tuama, Piarais Mac Gearailt, Seán Clárach, Brian Merriman, and many others. All died destitute.

Corkery’s book, written in sometimes verbose flowery language, is nevertheless a fascinating analysis of an Ireland that most “enlightened” readers of today want to bury. When Mícheál Martin, with a slavish acquiescence to the woke and the foreign masters, berates “backward looking nationalism” in the Irish Dáil, is it the people of The Hidden Ireland he is berating? Is it shame of a defeated people that prompts such cultural derision? Or is it that a thorough assessment of history is an inconvenience for the social engineers of today?

History does tell us that the replacement of a one population by another is usually a painful and traumatic process. Whether we like that or not, even if it hurts our “progressive” sensibilities, that is a truth borne out by an honest analysis of history. As a nation we can make of that what we will, but is it wise to ignore it?

Lorcán Mac Mathúna

A sold-out conference is being held today to mark the 100th anniversary since the publication of The Hidden Ireland.