There are three background facts that are key to comprehending Tuesday’s budget. Firstly, the economic environment facing the national budget has both deteriorated and got a lot more uncertain. Secondly, the global economic environment is deteriorating and only the bubble in Artificial Intelligence is saving the US economy (and thus the global economy) from recession. Thirdly, while Ireland’s governing parties – Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael – may pose as pragmatic, middle of the roaders they behave as dedicated social democrats whose economic policy is to the left of that of the UK Labour Party.

To an extent that is not fully appreciated, Ireland’s tax revenues are hopelessly dependent on US multinationals based here. It may be widely known that about three quarters of our corporation tax receipts come from this quarter. But what is less well appreciated is that – because our income tax system is heavily skewed to taxing higher earners and because multinationals are generally high payers – those employed by US corporations contribute a wholly disproportionate share of income taxes too. The same goes for value added taxes. All in all, I reckon that US multinationals contribute well over half of Ireland’s total tax revenues.

Now our industrial strategy is directly in Donald Trump’s crosshairs. He has stated “Ireland was very smart. They took our pharmaceutical companies away from presidents that didn’t know what they were doing. It’s too bad that happened. The Irish are smart; they’re a smart people. And you took our pharmaceutical companies and other companies through taxation, and proper taxation, and they made it very good for companies to move over there. We had presidents and people that were involved with this, and they had no idea what they were doing, and they lost big segments of our economy”.

In the first instance, President Trump has massively increased US tariffs. By increasing the price of goods made in Ireland relative to those made in the USA, he has put Ireland’s low corporate tax model under pressure. In 2024, Ireland exported €72.6b of manufactured goods to America. Apply a flat tariff rate of 15 per cent and you get a €10.9b increase in the cost of buying Irish imports into the USA. With 211,000 employed here in US subsidiaries that tariff bill is the equivalent, in cost terms, to increasing the salary of every employee here by over €50,000. Ouch!

The impact of tariffs has yet to fully emerge as most exporters shipped lots of goods across the Atlantic ahead of the tariff deadline. But its impact will be considerable. And, for economic activity and tax revenues here, that impact is likely to be sharply negative.

The other big problem with Trump’s tariffs is that there has been remarkably little domestic political opposition to them in the USA. There is no political cavalry about to ride over the hill to rescue Ireland from Trump’s tariffs. Usually, if an administration upends an economic policy that has stood for over half a century, we expect the opposition party to trenchantly oppose that policy reversal. This hasn’t happened. That suggests that the US political establishment now views Trump’s tariffs through his “America First” lenses and are quite happy to accept them.

As if the Department of Finance mandarins in Merrion Street didn’t have enough to worry about, economic growth now appears to be weakening both in the USA and at home. On Monday, Davy Stockbrokers published data showing a steady drop in the growth of tax revenues since the middle of last year. Excluding corporation taxes (which are highly sensitive to decisions made by just a handful of big US multinationals), tax revenues grew by 7.5 per cent in the year to June 30th, 2024. By contrast, over the last 12 months (in the year ended September 30th last) they grew by just over 3.0 per cent.

In the USA, economic growth is also coming under pressure even if that is being disguised by a rampant stock market, intoxicated by the possibilities of Artificial Intelligence (AI). According to economist David Rosenberg, real personal disposable income grew over the April-August period at an annualised rate of minus 1.2 per cent. Excluding Tech/Communication Services (the epicentre of the AI bubble), profits of large US companies are growing at just 1.5% per annum. That’s less than the rate of inflation. The sharp rise in the price of gold, up 50 per cent in dollar terms over the last 12 months, is a warning sign that troubles may be brewing in the monetary system, in the world of paper money.

The final factor that explains yesterday’s budget is the leftward slant of Ireland’s politics. While RTÉ insists on telling us that Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael are parties of the centre-right, consider key aspects of the Irish income tax system and compare them to those of the Labour-governed UK system.

The top marginal rate of deductions here is 52 per cent, comprising income tax (41 per cent), PRSI (4 per cent) and USC (7 per cent). In the UK it’s just 47 per cent, including PRSI. A single person starts paying the top rate of tax here on an annual income of a mere €44,000. In the UK, you don’t pay top-rate tax until you are earning over £125,140 (or €144,150). The minimum wage is €14.15 an hour here, in the UK it’s £11.44 (or €13.17). Yet the UK is run by socialists while Ireland is ruled by centre-right parties? Give me a break.

We have an economy where the weakness of our domestic private sector has been disguised for many years by the spectacular performance of the American multinational sector. Facing a future where the multinational sector is likely to deliver a lot less – this week saw the co-announcement from Pfizer that it will also be investing $70 billion to expand drug manufacturing in the U.S. – we need to dramatically build up the domestic sector. Nothing in this budget even touched on this fundamental challenge.

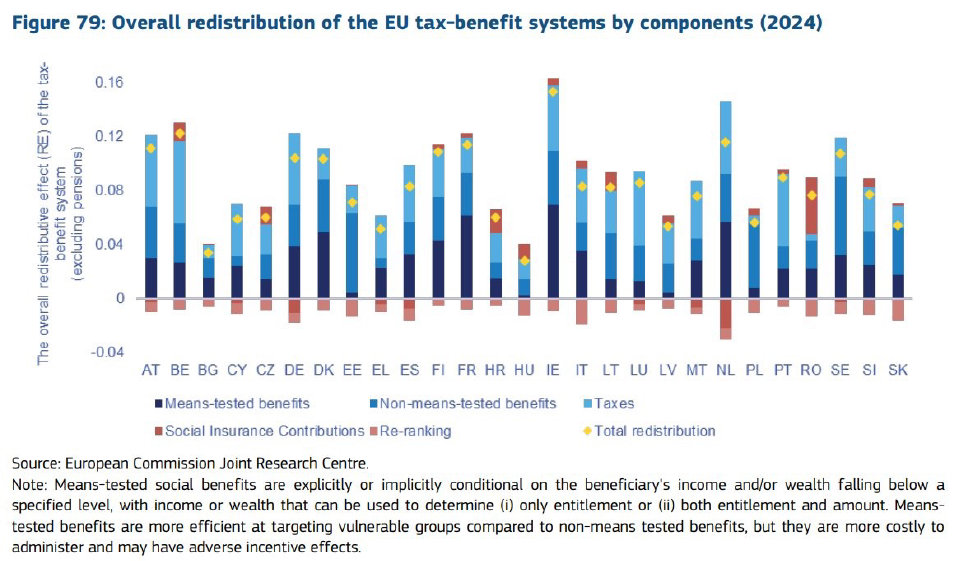

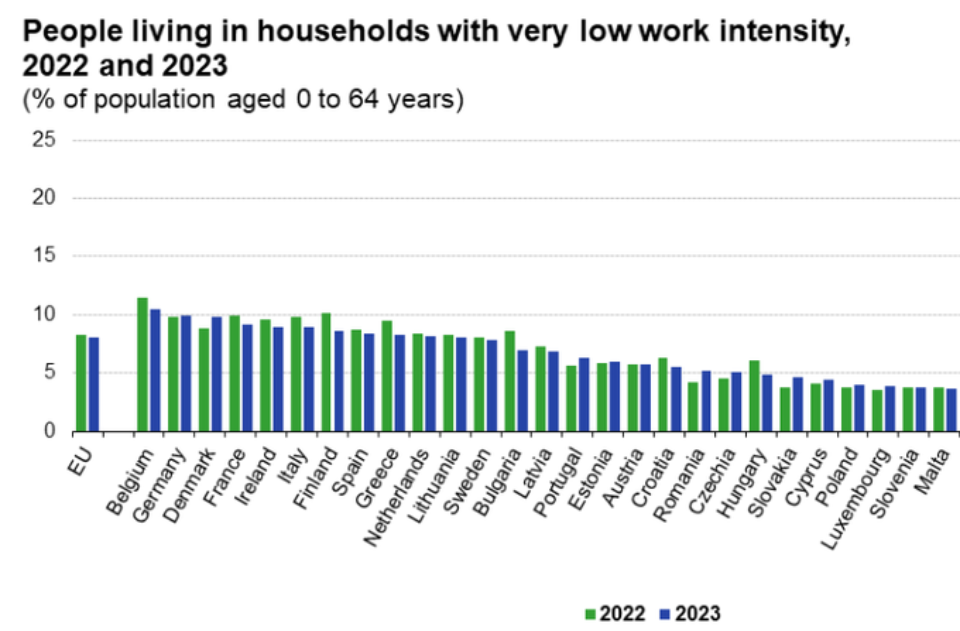

Ireland’s leftward focus on income distribution means that we have the system in Europe that does the most to tax income and to boost welfare. This discourages activity – it’s one of the factors behind Ireland’s shortage of workers and large-scale immigration. It encourages inactivity – we have one of Europe’s highest levels of people living in households with very low work intensity.

Now that the US multinational gravy train looks like it may be derailed by President Trump, it’s time to sharply incentivise domestic economic activity. How did FF and FG respond to this challenge in yesterday’s budget? They index-linked welfare rates – the inactive are rewarded. They failed to index-link tax credits or tax bands – the active are ignored. Finance minister Paschal Donohoe is Fine Gael’s leading thinker. His party’s website brandishes the slogan “securing the future”. That’s about as believable as the slogan from Jim Gavin’s campaign website “Never give up”.